We’re looking forward to introducing you to Cynthia Reeves. Check out our conversation below.

Hi Cynthia, thank you so much for taking time out of your busy day to share your story, experiences and insights with our readers. Let’s jump right in with an interesting one: What do the first 90 minutes of your day look like?

The first ninety minutes of my day unfold with the kind of ritualistic precision usually reserved for monks, except mine involves caffeine and calculated procrastination. I begin with two cups of coffee strong enough to qualify as a controlled substance, each one drowned with extra cream (not milk!) because life is short and calcium is important. As the caffeine revivifies me, I tackle the New York Times word games and crossword puzzle convinced that this counts as warming up my writing muscles, or at the very least, that I haven’t suffered sudden-onset dementia. From there, I’ll do absolutely anything—reorganizing the spice cabinet alphabetically or swiffering spiderwebs that have materialized overnight—to avoid sitting down at my computer. Only when every possible delaying tactic has been exhausted do I finally surrender to the blank page and pick up where I left off the day before.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

When as a child I composed stories on my mother’s Remington typewriter, I fancied myself a fiction writer. Those stories were based upon tales she and my uncle, first-generation Italian Americans, told over obligatory Sunday afternoon dinners and Christmas cookie-making marathons. That generation is now gone, but their influence in inspiring my writing career lives on in that typewriter, displayed on my bookshelves and still housing the last of many ribbons fixed halfway between its beginning and end.

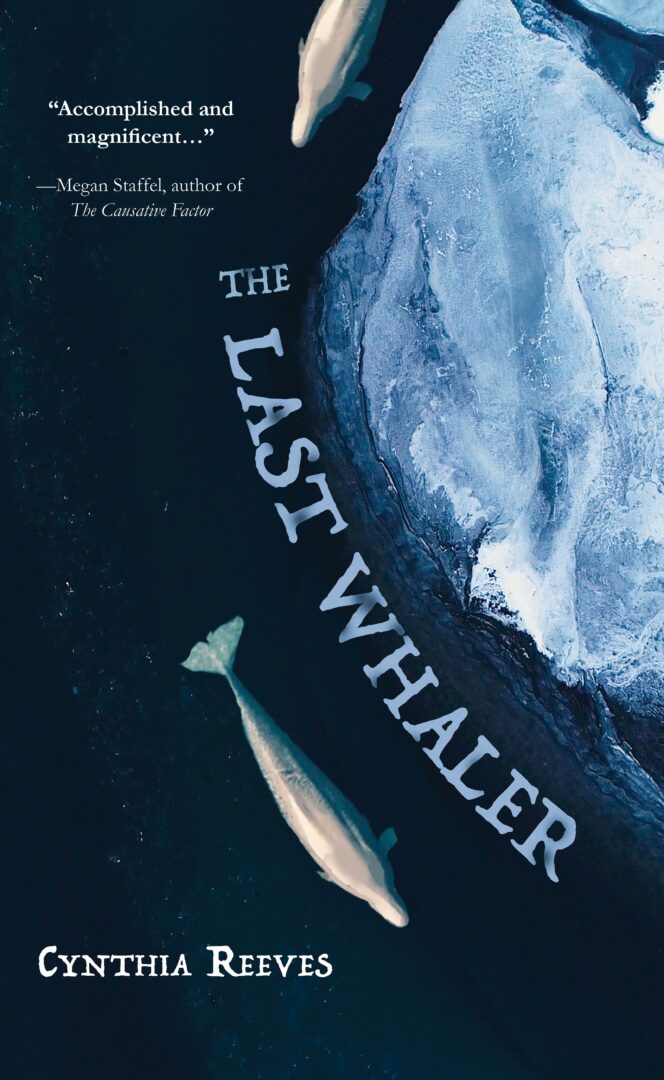

What makes my most recent work distinctive is the setting—Svalbard, an archipelago located halfway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. My lifelong interest in the Arctic started in childhood reading tales of doomed polar explorers. But it was my participation in the 2017 Arctic Circle Expedition, an artist-scientist residency that sailed Svalbard’s western shores, and three subsequent residencies in Longyearbyen, that have inspired my writing since then. The Last Whaler (Regal House Publishing 2024) is the most ambitious of this work. During the voyage, we landed at the site of an old beluga whaling station called Bamsebu on the southern shore of Van Keulenfjorden. Stretching to the horizon were whale bones, piles and piles of bleached beluga bones bearing silent testimony to the slaughter that occurred there in the 1930s.

The Last Whaler follows Tor Handeland, a beluga whaler, and his wife, Astrid, a botanist specializing in Arctic flora, who are stranded during the dark season of 1937-38 at his remote whaling station on Svalbard. Beyond enduring the Arctic’s twenty-four-hour night, the couple must cope with the dangers of polar bears, violent storms, and bitter cold—and Astrid’s unexpected pregnancy. The novel is a meditation on the resilience of the human spirit, the abiding power of love and remembrance, and the fragile threads that connect us to each other and, especially, to our environment.

Two years of research for The Last Whaler yielded a wealth of other stories including that of Anna Charlier, the fiancée of Nils Strindberg, who disappeared along with two other men during their ill-fated attempt to fly over the North Pole in a hot-air balloon in 1897. Their bodies were discovered in 1930 on the barren island of Kvitøya in the Svalbard archipelago. Charlier’s obsession with Strindberg is reflected in her dying wish to have her heart buried next to his grave in Stockholm. Though much has been written from the explorers’ point-of-view, little is written from Charlier’s perspective. That’s the novel I’m in the earliest stages of developing.

Amazing, so let’s take a moment to go back in time. Who taught you the most about work?

Hard work is my inheritance, a gift bestowed by both sides of my family.

My father grew up on an isolated farm at the end of a dirt road in rural Maine. Neither of my grandparents earned a high school diploma, so their livelihoods were devoted to manual labor. My grandfather supported his family by hauling lobster traps, raking blueberries on the hills behind his small Cape Cod farmhouse, and building stone walls throughout Maine. His mother canned sardines at the Port Clyde Sardine Factory and made woolen blankets for the military at the Knox Woolen Mill in Camden. I learned only recently from an old family friend who grew up with my father that my grandmother took the job at the mill and rented an apartment in “town” so that my father could attend the best high school in the area. For his part, my dad paid his way through college by playing trumpet in a swing band, often staying up into the early morning hours for a gig before heading back to college to study for a degree in chemical engineering. Throughout his life, he rarely took a day off from his consulting business, often working late into the night in an office he kept in our basement.

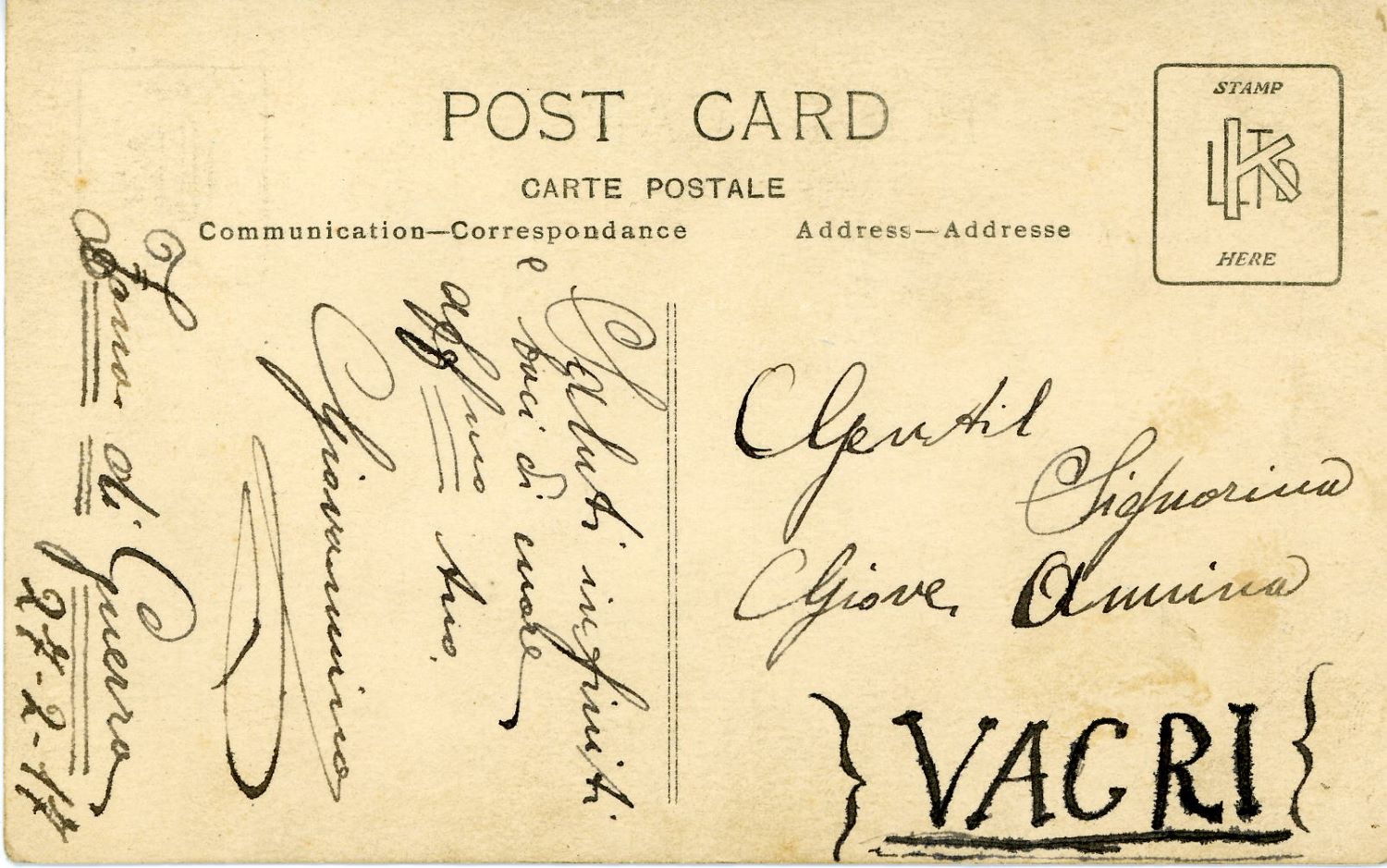

My mother was the child of Italian immigrants. My grandfather was a POW in World War I. He returned home to Vacri in Abruzzo only long enough to save enough money as a tailor to emigrate to America in 1922. My grandmother, a bobbin lacemaker, stayed behind for seven years until they could afford to have her join him. They had a son who died in Italy from typhoid fever during that seven-year separation. My grandmother arrived in America on the very day the stock market crashed in 1929, but owing to the tailoring business my grandfather had worked hard to establish, they were able to eke out a living during the Great Depression and the war. My mother was a full-time homemaker, mother to five children, until my father’s consulting firm suffered a financial setback. Several months pregnant at the age of 41, she earned a real estate license and spent the rest of her life selling houses to help support our family.

What all these lives taught me was the value of hard work and the fortitude to persevere even in the face of extreme adversity. I’ve been lucky. I never faced the more serious hardships of my forebears. I started working in my teens as a babysitter and waiter before moving on to internships that paid my way through college and prepared me for a professional career in management consulting that lasted a decade. With the support of my husband, I left the business world to pursue writing seriously. Those ten years gave me financial security, a desire borne of growing up in a family that always struggled to earn a living. I do wonder, however, how different my life might have been had I started writing immediately after college.

When you were sad or scared as a child, what helped?

I’ve always had an overactive imagination. Growing up, I invented an imaginary friend—Mitchell—whom I’d call on to protect me. He was my guardian angel, a friend always by my side. Otherwise, I had few close friends. I was that typical, nerdy kid with glasses. Mitchell was a way to deflect my classmates’ relentless teasing for being overweight and awkward.

Another escape was books. My favorite pastime was to spend hours in the local library, devouring tales of mythical beasts and intrepid explorers. And I found solace in being the top student in my class, which likely didn’t help ingratiate me to me peers. But it’s interesting that academic accomplishment could soothe some of the most hurtful taunts and bullying.

As I write this, I’m reminded of how these experiences are fodder for my fiction. So I am, in a strange way, grateful even for childhood ordeals.

Next, maybe we can discuss some of your foundational philosophies and views? What do you believe is true but cannot prove?

I believe there is an afterlife but of course cannot prove it.

I’ve vacillated between believing and not believing throughout my life. My mother was a devout Catholic. No Sunday Christian, she provided a true example to her children of living the faith. Even in the last days of her life, she prayed the Rosary, which gave her great peace.

I was raised Catholic, steeped in a belief in the afterlife. But as the Church’s pedophilia scandal came to light, I grew disenchanted and “fell away” from the formal practice of my faith. I hid this apostasy from my mother, knowing it would have broken her heart. I wrestled with the idea of an afterlife—wanting it to be true so I might see again those I’ve lost, even as I questioned the irrationality of the belief itself.

Two mystical occurrences, however, gave me pause. In 1999, when I lost my best friend to cancer, I was cooking for the many out-of-town guests her husband expected that evening. As I worked, I found myself wondering—pointlessly—whether now that she was gone, she was at peace with dying. At that very moment, I sensed something behind me: a strange wash of light, as if the sun had slipped through the walnut trees shading my backyard and found its way into the darkest corner of my kitchen. I turned but saw nothing—only felt that my friend had passed through. The second occurrence came seven years after my mother’s death, as my uncle lay dying. Despite his dementia, he was adamant that he conversed with my mother every evening. I tried to brush it aside, but his sudden lucidity during those moments made it difficult to ignore.

Two decades of experiences with death, and with intimations of an afterlife, came together in the final story of Falling Through the New World, “All This the Heart Ordains.” It took me ten years after my mother’s passing to write what ultimately became a love letter to her and an articulation of what I now hold to be true—that there is a life beyond this one. The story turns on a pilgrimage my mother and I took in 2009 to the shrine of the Holy Face of Manoppello in Italy, where a cloth preserved in a reliquary is believed to be the veil that covered Jesus’ face in the tomb. While the details are fictionalized, the crux of the story remains: an adult daughter grappling with her faith and finally coming to understand her mother’s. Here are the final paragraphs:

It was early morning, the sun just coming up when I parked my rental car at the base of Via Cappuccini. I forgot to bring a rosary—truth be told, unlike you, I never carried one—but as you used to say, that’s why God gave us ten fingers. I decided to walk the whole way, as my maternal forebears did, stopping at each Station of the Cross and praying through all the mysteries, saving the joyful ones for the Holy Face as we did years ago. […]

When I reached the cobbled plaza in front of the basilica, Casa del Pellegrino beckoned. But it was getting near noon, and I wanted to complete my mission before the church closed for riposo. The sexton was nowhere to be found, but the doors were open and the lights were on, so I walked up the central aisle toward the altar, my eyes fixed on the reliquary. As I approached, the Holy Face came into focus—the same peace in His open eyes, as if He’d just awakened. The closer I came the more details appeared—the crooked nose, the tips of His incisor teeth, the edema on His cheek. Walking up the short flight of steps to the prie-dieu behind the altar, I knelt and looked frankly at the face that stared back at me. I said the Joyful Mysteries, took a holy card, and mouthed the Prayer for Immigrants in ersatz Italian.

My knees ached, but still I knelt there, my hands folded in prayer. I thought about you. I thought about your mother and your mother’s mother. I thought about the daughter—having waited too long—that I could never have. Then I blessed myself and pressed my hand against the glass to cover the bloodstain on Christ’s cheek. And Mom, I swear, it was warm to the touch.

Thank you so much for all of your openness so far. Maybe we can close with a future oriented question. When do you feel most at peace?

I have always loved the water. Pond or lake, river or waterfall, the vast breathing ocean—it doesn’t matter. I feel most at peace watching sunlight quiver across a lake’s surface, waves hush against a sandy beach, boats tug gently at their moorings, or a river coil and uncoil along a stony shore.

Five years ago, that love drew me to settle in Midcoast Maine, across from Camden Harbor and its shifting seasons: the lively summer docks, the slips emptying one by one in autumn, the stark shimmer of winter water, and the slow, hopeful return of boats in spring. A love of the water, like a stubborn work ethic, is part of my inheritance. My grandfather was a lobsterman, and on summer vacations he would take us fishing from the very harbor I now watch over each day from my office window.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://cynthiareeveswriter.com

- Instagram: @cynthia_p_reeves

- Twitter: @cynthiapreeves

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/cynthia.reeves.921

Image Credits

Not applicable

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.