Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Gabrielle Riegel. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Gabrielle, appreciate you sitting with us today to share your wisdom with our readers. So, let’s start with resilience – where do you get your resilience from?

I didn’t get resilience, I had it forged into me.

Between 18 and 25 I was basically living in hospitals with nephrostomy tubes and a suprapubic catheter, going septic over and over, on palliative care while my friends were just starting their adult lives. I also have severe anxiety and a panic disorder, and for most of my life that honestly stopped me from doing things that scared me.

Then I hit a point where I didn’t have the option to avoid anything anymore. All the stuff I was most afraid of – losing my parents, nearly dying, being alone, handling legal and medical decisions while critically ill – just started happening, one after another.

On top of that, my country – yes, the big one everyone is talking about on international news – has been sliding into open fascism, and the laws are being quietly tweaked to target disabled queer women like me. I was born and raised there. My whole family was born and raised there. My ancestor George M. Dallas was literally the 11th vice president of that place. I doubt he ever imagined I’d have to flee the same country his name is all over because it wasn’t safe for me as a disabled queer woman.

So my resilience comes from being forced to move through the fear instead of around it.

I learned to sign complex forms half-conscious, doing estate paperwork from a hospital bed, surviving six-hour panic attacks where I’m hyperventilating and ripping my hair out, and then still having to get up and talk to doctors or lawyers afterward. And then, right after major surgery and “graduating” from palliative care, leaving my country abruptly when I didn’t even know if I was recovered enough to survive the move. It was dangerous, but staying was more dangerous, so I took the chance. I’m glad it worked.

I still get panic attacks sometimes from the trauma, but it’s slowly getting better as I work through what happened.

It wasn’t some cute self-care journey. It was “adapt or die” on repeat, until not quitting became my default setting.

Let’s take a small detour – maybe you can share a bit about yourself before we dive back into some of the other questions we had for you?

Right now I’m building a life that sits at the intersection of law, human rights, and art.

Professionally, I’m preparing for law school. After everything that happened to me in the U.S. as a disabled queer woman watching my own country slide toward fascism, I want to be on the side that’s actually fighting back. The laws are literally being tweaked to target people like me, and I ended up having to leave the place I was born and raised, where my entire family is from, because staying was more dangerous than moving countries right after major surgery.

Law is also kind of in my blood, with my ancestor being an early vice president, and my mom being a lawyer too. Picking up that line and turning it toward human rights work feels like both a continuation and a correction of my family history.

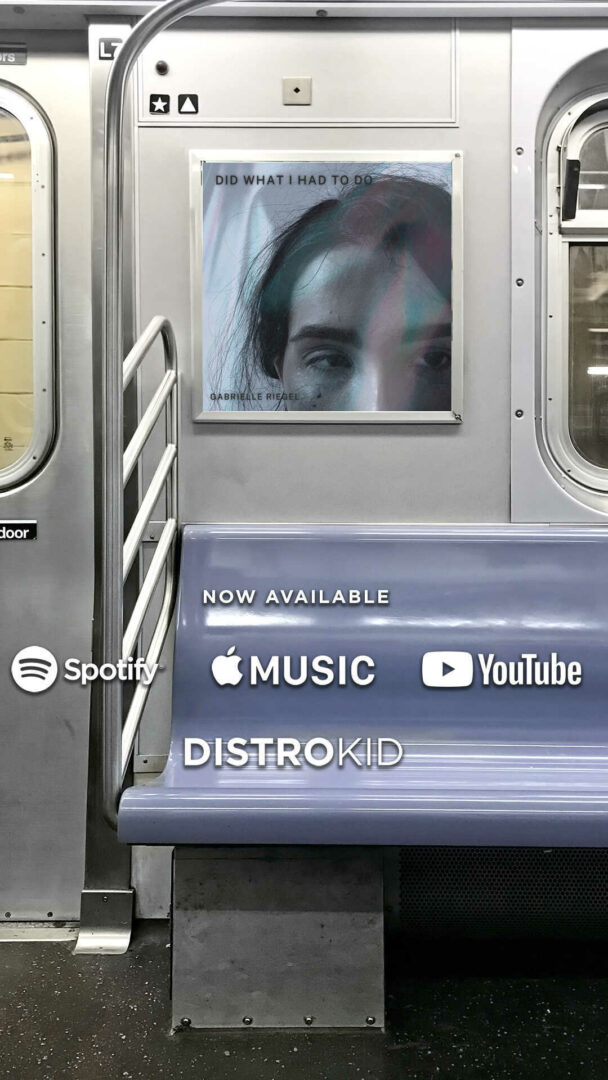

On the artistic side, I’m an electronic music producer and vocalist. I was originally trained as an opera singer until I got too sick to keep performing around 21. Stuck in a hospital bed with way too much time and way too many tubes, I opened GarageBand out of boredom and started teaching myself to produce. Now I release electronic dance music that’s on Spotify and Apple Music. It started more as “something to do so I don’t lose my mind in here” and evolved into a real side career and a way to transmute a lot of what I’ve been through.

I’m also deeply involved in visual arts and fashion. My mom had a fine arts degree, my uncle is a musician, and I’ always was that kid who has to make things, whether it was painting, oil pastels, weird outfits, whatever I could get my hands on. I’m still the same, it’s only gotten more pronounced as I’ve gotten older.

Since moving to Canada I’ve been slowly plugging into the local arts and fashion scene in Toronto, collaborating, showing up to events, and building community.

So my “brand,” if you want to call it that, is a mix of survivor, future human-rights lawyer, and multidisciplinary artist. I’m taking experiences that should have just broken me and turning them into music, visuals, and eventually legal work that pushes back on the systems that made survival this hard in the first place.

There is so much advice out there about all the different skills and qualities folks need to develop in order to succeed in today’s highly competitive environment and often it can feel overwhelming. So, if we had to break it down to just the three that matter most, which three skills or qualities would you focus on?

Looking back, the three things that carried me weren’t pretty or polished.

First, radical adaptability. I went from young opera singer in my undergrad of university with some chronic illnesses to palliative‑care patient with nephrostomy tubes and a suprapubic catheter, and then to a disabled queer woman having to flee the country my family had been in for centuries. I pivoted from the stage to teaching myself electronic production in GarageBand from a hospital bed, and later from “professional patient” (although I hate that wording it can be true in some situations and that is what it felt like), to rebuilding a life in Canada. That constant forced reinvention is what kept me moving. If you want to build this, put yourself in new situations before life does it for you: new mediums, new roles, new places, and let yourself be bad at them at first.

Second, turning pain into work and art instead of letting it just sit in my body. The panic attacks, grief, and medical trauma all got poured into music, painting, fashion, and eventually into a political awareness that what happened to me was not just “bad luck,” it was systemic.

That’s what pushed me toward law: realizing that the same systems that almost killed me could be studied, challenged, and rewritten. Law runs in my family, as I said; but ultimately surviving all of this gave me the *why* and the clarity about focusing on human rights and disability justice. Every hospitalization, every fight with bureaucracy, weirdly became prep work for law school because I already know how those systems feel from the inside.

Third, an extremely unglamorous form of resilience. Mine looked like six‑hour panic attacks and then still getting up to sign forms, talk to doctors, or deal with lawyers and immigration paperwork. It looked like getting on a plane not long post-surgery because staying was more dangerous than leaving.

If you’re early in your journey, focus on tiny acts of “I did it anyway.” Send the email, finish the track, show up to the appointment, book the advising call about the program you’re scared to apply to. Stack enough of those and, even with anxiety and trauma, you start to trust that you can fall apart and still move forward – and, if you want, translate that into something bigger, whether that’s law school, art, or whatever form of resistance calls to you.

Thanks so much for sharing all these insights with us today. Before we go, is there a book that’s played in important role in your development?

“The Bell Jar” has been my emotional comfort horror book for years. On paper, Sylvia Plath and I don’t match: she’s a brilliant 1950s poet getting brutalized by psychiatry. I’m a disabled queer woman getting brutalized by modern medicine and politics. But the feeling is identical – being sealed under an invisible dome while everyone else’s life keeps going in full color. When I was cycling through nephrostomy tubes, palliative care, and six‑hour panic attacks, her bell jar was exactly what it felt like to watch the world move on without me.

What hit me hardest wasn’t the “sad girl” aesthetic people meme Plath into, but how violent institutions can be while still calling it treatment. The electroshock scenes, the doctors talking over her, the quiet decision that she’s more object than person – it’s the same energy as being medically complex in a system that just wants you to either comply or disappear. Reading a 1950s psych ward and recognizing 2020s hospitals and courtrooms was almost clarifying, in a sick way.

I also love that she still had a career. She published. She mattered. That was proof that you can be wildly unwell and still make work that outlives you. At the same time, I’m haunted by the fact that she never had the legal protections I enjoyed for much of my life even though I’m now watching get rolled back. She lived before disability rights, before real patient protections. I’m living after them, during the slow, malicious “undo” button. That gap is part of what pushed me toward human-rights and disability law: if she’d had the safeguards I’m fighting for, her story might have ended differently.

So the nuggets of wisdom from The Bell Jar aren’t motivational quotes. They’re more like a prophecy and a dare. Institutions are not neutral, laws are life support, and survival is political. My takeaway wasn’t “it gets better”; it was “document everything, make art out of the rot, and then go learn the law so you can start ripping the bell jars off other people’s heads.”

Contact Info:

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ellestomalife?igsh=MW9mMjZjNjhra3Myaw%3D%3D&utm_source=qr

- Other: Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/artist/4zlY2PYk9iO1582B7Iwh0V?si=rAWYlydbT0WAy7twULCAmw

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.