We’re looking forward to introducing you to Seneca Kristjonsdottir . Check out our conversation below.

Seneca, really appreciate you sharing your stories and insights with us. The world would have so much more understanding and empathy if we all were a bit more open about our stories and how they have helped shaped our journey and worldview. Let’s jump in with a fun one: What makes you lose track of time—and find yourself again?

Working in the garden

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

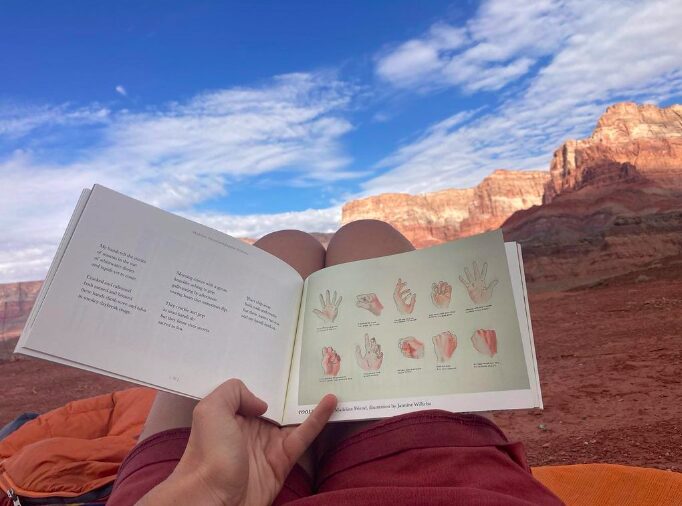

I am one of the founding editors of The Thalweg. We are a creative publication and community rooted in rural, agricultural, outdoor, and wilderness-based landscapes. We believe these places — and the people who live and work in them — have vital stories to tell. Our name, “thalweg,” refers to the deepest part of a canyon: the navigable channel where the current runs strongest. And in that spirit, our publication is a channel for voices often under-heard.

Each issue brings together 15 to 18 contributors — writers, visual artists, land stewards, guides, ecologists, farmers, hunters, rangers and more — all drawn to the strange and beautiful ways humans metabolize wild landscapes. We publish a limited print run and then archive the work online once the print copies are sold through.

What makes The Thalweg special is our commitment to community and place. We’re volunteer-run and proudly pay artists and writers for their work. We operate on a sliding scale for our issues because we believe access matters.

A little about me: I studied ecology and bee husbandry at Goddard College, and I’ve worked seasonally as a guide on rivers like the Salmon and Snake in Idaho and in the Grand Canyon region of Arizona. Outside of that, I’ve been a seamstress, soft-goods designer, beekeeper, bartender, lab-manager — always circling back to the idea of how humans and nature live in relationship.

Right now, The Thalweg is working on our upcoming issue focusing on Southwestern Desert creatives, and expanding our programs. We’re supported through donations, grant funding, and our fiscal sponsorship with Northern Arizona Book Festival, which allows us to operate as a nonprofit.

Great, so let’s dive into your journey a bit more. What’s a moment that really shaped how you see the world?

When I started my undergraduate degree, I wanted to be a beekeeper. So I enrolled at Goddard College, which had a self-directed study program that let me design my own degree—with only two requirements: my thesis had to be ecologically and socially contextualized. At the time, I found that frustrating. Beekeeping, I thought, was about science, not society.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. After reading countless books on superorganism theory and swarm behavior, I came across ‘The Forgotten Pollinators’ by Stephen Buchmann and Gary Paul Nabhan. It revealed how thousands of native bees, moths, and birds evolved alongside the landscapes of the American West—and how they’re disappearing due to the dominance of European honeybees and industrial agriculture. Honeybees, I learned, are an introduced, even considered an ecologically invasive species.

That book cracked something open for me. I began to see how colonial histories have shaped our landscapes and food systems, and how human values continue to drive ecological change. In short: our world is far more complex than we perceive from within our own narrow experience. This realization made me question everything I thought I understood—about wilderness, about the supposed divide between humans and nature, and about our disconnection from the food, water, and air that sustain us.

That whole liberal arts education really bit me in the ass, to say the least—but I now walk through life with a wider lens, always trying to notice the blind spots in the stories I tell and seeking a deeper, truer understanding of the world around me.

What did suffering teach you that success never could?

Spending long stretches working in the backcountry has a way of stripping things down to their simplest form. Out there, comfort is rare and control is mostly an illusion. You get cold, wet, blistered, hungry — and still, the work of finding a place to sleep and feeding yourself has to get done. There’s no opting out when the weather turns or the river rises.

Those experiences have taught me more about strength and resilience than any success ever could. It’s one thing to feel capable when everything goes according to plan, but it’s another to find grace when nothing does. Out there, I’ve seen how people endure — how humor surfaces in the middle of a desert monsoon, how kindness can expand when folks experience uncomfortable temperatures for days in row, how even in the dark moments- conflict often makes us stronger, how we all see each other more clearly under environmental stress.

The backcountry has shown me that the human spirit is sturdier than we give it credit for, and that our limits are often just the edges of our comfort, not the end of our capacity.

I think our readers would appreciate hearing more about your values and what you think matters in life and career, etc. So our next question is along those lines. Where are smart people getting it totally wrong today?

one of my favorite poets Natalie Diaz writes,

“America is a land of bad math and science. The Right believes Rapture will save them from the violence they are delivering upon the earth and water; the Left believes technology, the same technology wrecking the earth and water, will save them from the wreckage or help them build a new world on Mars.”

Okay, we’ve made it essentially to the end. One last question before you go. What will you regret not doing?

Actually learning how to surf.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.thethalweg.com

- Instagram: @the_thalweg

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.