We’re looking forward to introducing you to Charles Ingham. Check out our conversation below.

Good morning Charles, we’re so happy to have you here with us and we’d love to explore your story and how you think about life and legacy and so much more. So let’s start with a question we often ask: When was the last time you felt true joy?

At the risk of sounding like a bliss ninny, I am fortunate in being able to say that true joy is no stranger to me.

But here perhaps is a recent moment of unalloyed joy that caught me by surprise. In early September, my wife and I were in Chicago. As we walked over the Canal Street bridge, an elevated train started to make its way across the upper deck, and we stopped to watch the show, leaning back on the railing to look up through the superstructure. As the train cars passed, their vibration transmitted itself across the ironwork, through the railing in the small of our backs, and into our bodies. This was no ordinary massage: Industry itself was borrowing our anatomy and talking loudly. Train, bridge, body – we were singing the body mechanical. An utterly joyful song.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

I am a photographic artist living and working in San Diego. Born in England, I received my undergraduate and postgraduate degrees from the University of Essex before moving to California to teach in higher education. I am a studio artist at ArtHatch in Escondido and a member of the Snow Creek Photographers Collective.

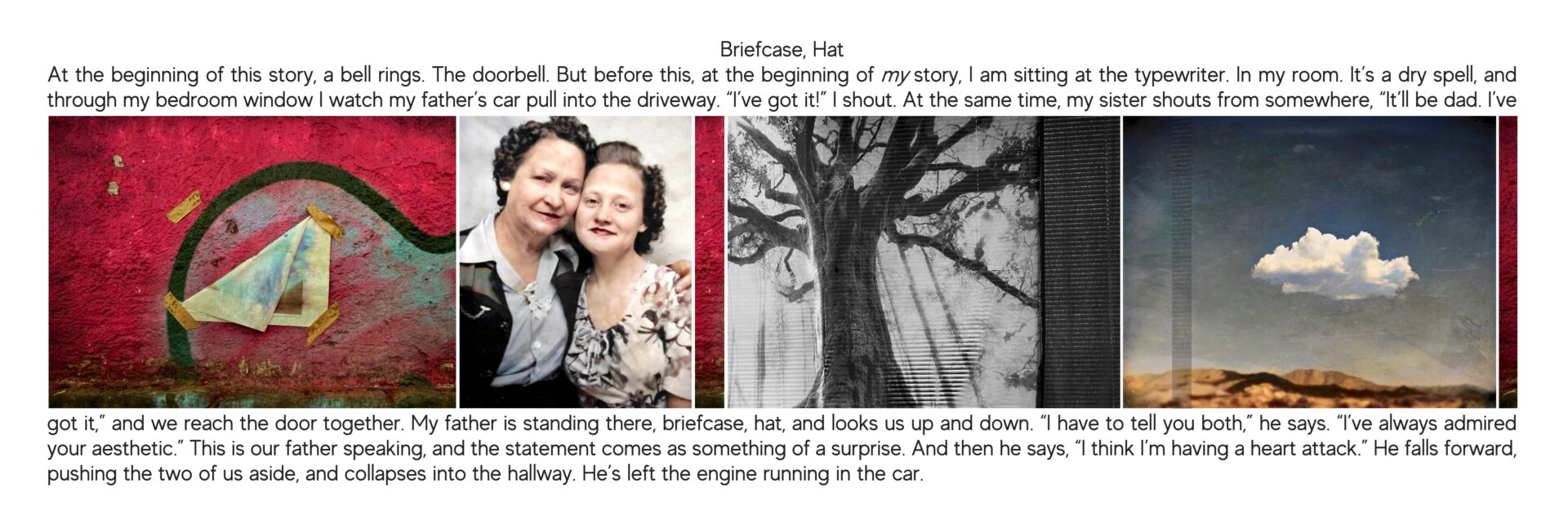

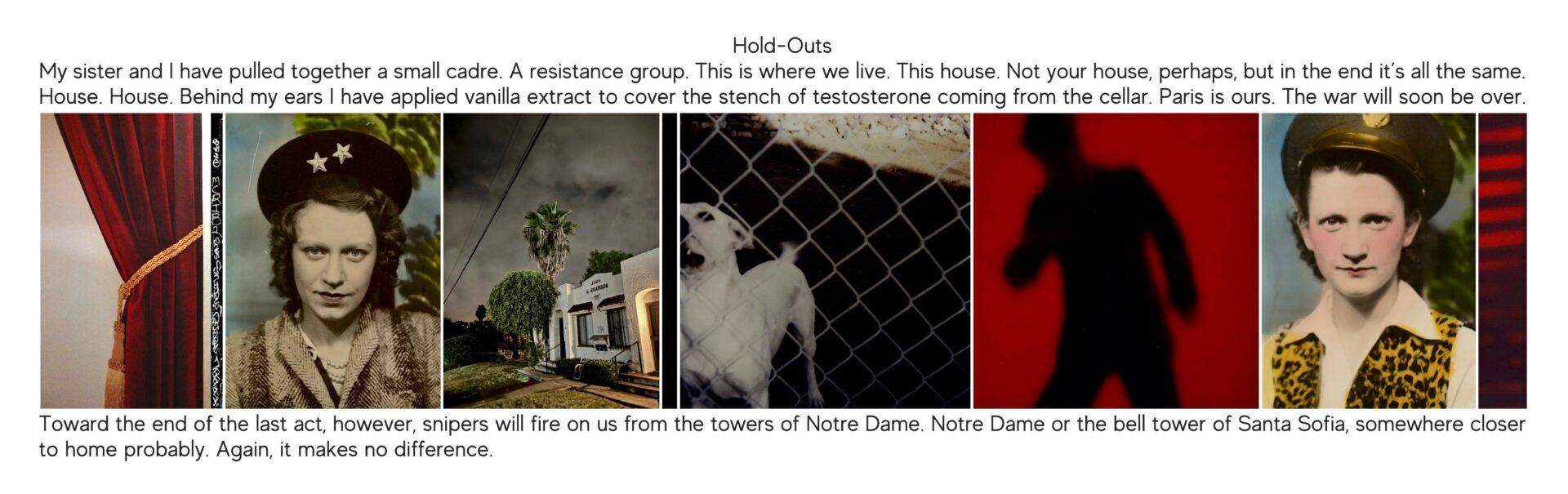

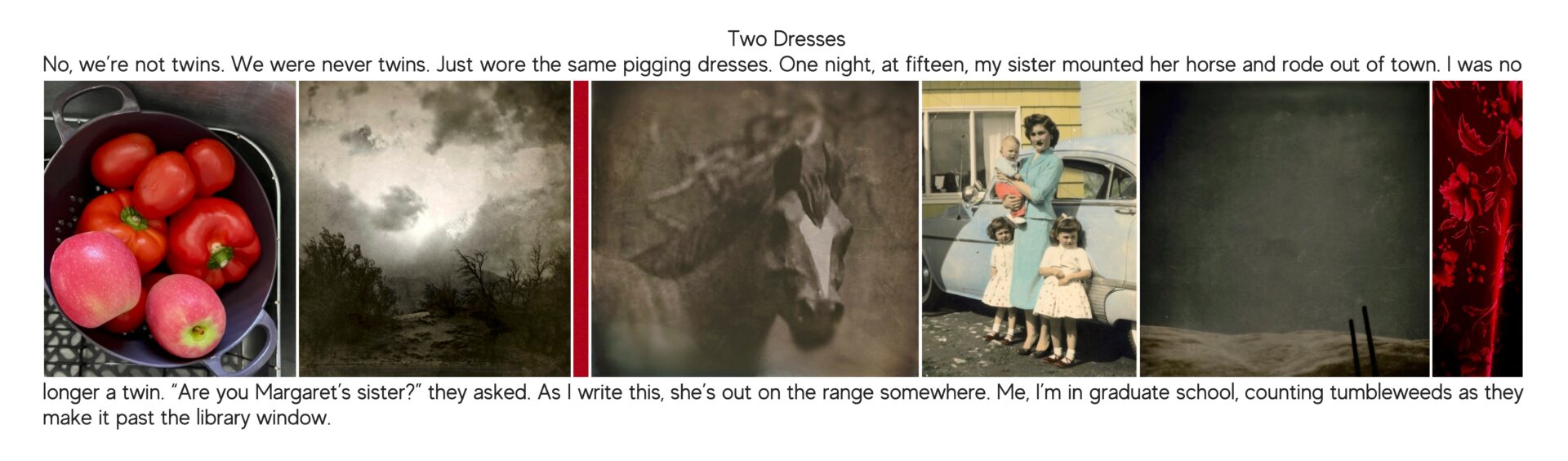

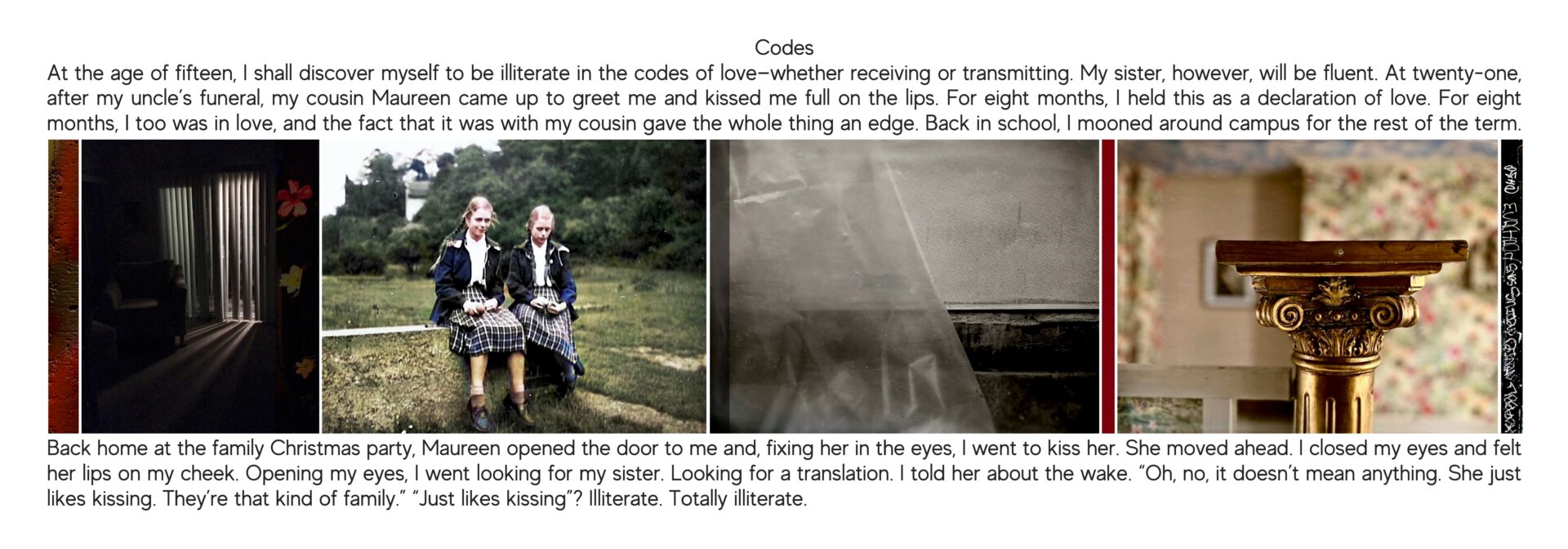

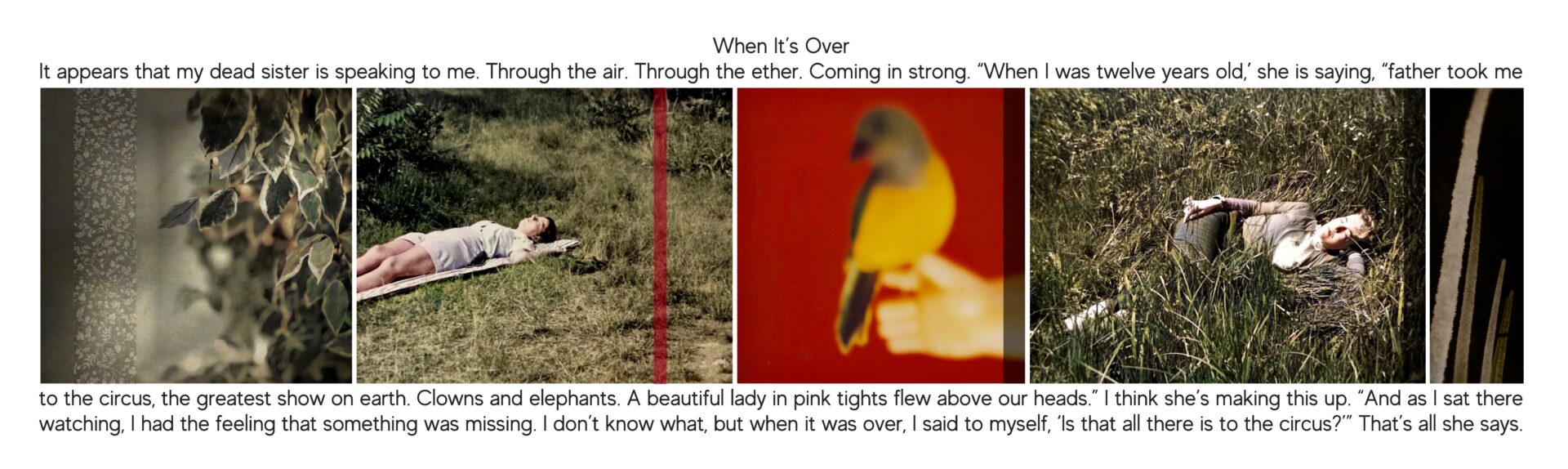

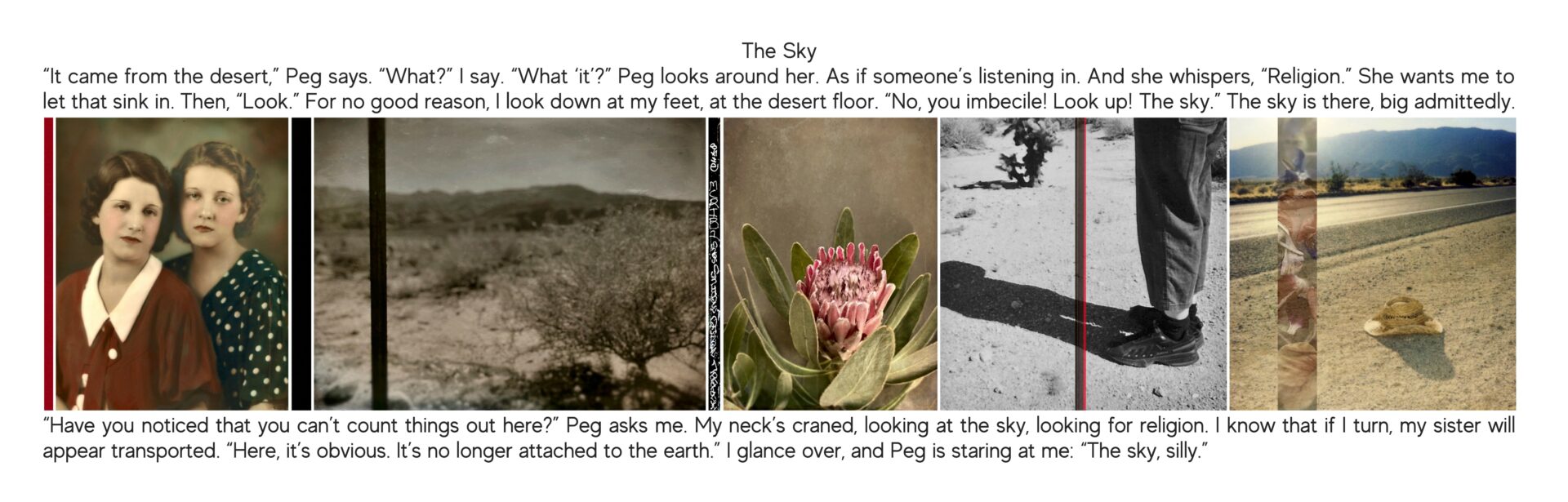

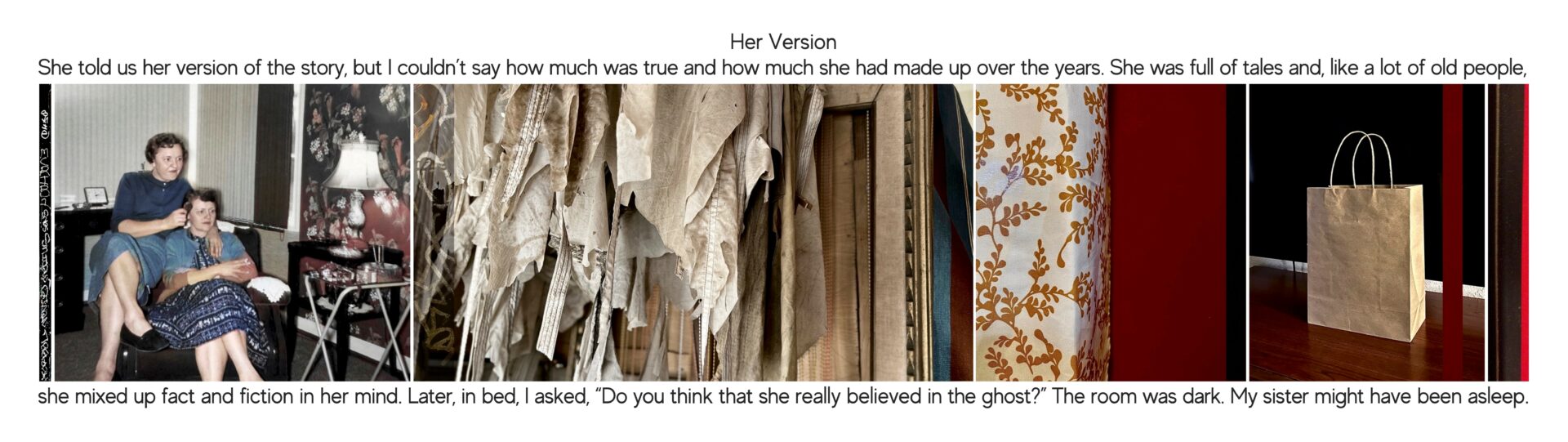

As a conceptual artist, I create photo-narratives that are hybrid forms, transgressing distinctions between the verbal and the visual. My art represents a combinatory aesthetic; each work constitutes a whole made up of parts, creating something of a symbiosis. Many visual references are obvious; some of the bones, sinews, and other connective tissue that hold a particular narrative together work within the piece’s own logic, a logic that viewers find for themselves. Here, the artist makes the work, and that work has an agenda, but a significant part of that agenda is for the viewer to find something of (or for) themselves within these images and words.

Great, so let’s dive into your journey a bit more. Who taught you the most about work?

In my first year as an undergraduate at the University of Essex, I quickly realized that I had to unlearn most of what I had previously been taught about literature, writing, and art. A pivotal point came during a lecture given by Herbie Butterfield, one of my professors. Speaking about the work of the poet Walt Whitman, Herbie suddenly broke down in tears. I had never seen this before. But I got it. Herbie taught me how to teach (as I would go on to do later in life) and how to explore a work with such intensity that one could quite appropriately be brought to tears – and to be unembarrassed about doing that in public. I have carried Herbie Butterfield and Walt Whitman with me ever since; indeed, at the risk of sounding completely pretentious, Whitman was one of the major factors that led me to become an American citizen. It’s not pretentious; it’s true.

Is there something you miss that no one else knows about?

I am fond of the country in which I grew up, but I don’t miss it. However, there is one British cultural artefact that does, when I let it, deliver a sharp pang of emotional loss: the 99, a soft-serve ice cream cone in which is embedded a half-size Cadbury chocolate Flake. Sold from ice-cream trucks, they are a little difficult to explain. You have to be there, the melting ice cream running down your hand. The problem is that I am now a vegan, and the fantasy of the 99 serves only to taunt me. Why it is called a “99” is undetermined, frankly adding to its power among British origin myths.

Next, maybe we can discuss some of your foundational philosophies and views? Is the public version of you the real you?

Unfortunately, yes.

Okay, so let’s keep going with one more question that means a lot to us: Could you give everything your best, even if no one ever praised you for it?

I’m a perfectionist, a trait that can sometimes be annoying or handicapping, but I wouldn’t be without it. As I write this, I find that last statement to be a little surprising; I have a punk background, and I love the ethos of immediately acting upon an artistic impulse and celebrating a deliberate anti-professionalism. While my work is exact and exacting (and not easily achieved), I also celebrate the use of readily accessible and rudimentary technologies. In the series that I am working on now, I include Polaroid photographs and celebrate the inevitable flaws in that miraculous but clunky photographic process. I am also especially happy when a photograph that I took a day ago becomes part of a new work. This nod to a DIY approach aside, the person that I am obliges me to give everything my best. A long time ago I was working in factory that manufactured cans, and my job was to operate a manual forklift. With it being a long time ago, I was reading Kerouac’s On the Road, and I took to heart the example of Dean Moriarty working as a parking-lot attendant. My memory is that Dean took a job of cold drudgery and transformed it into a fine art, in which the reversing of large cars into narrow spaces became a choreographed dance of glorious precision. Whatever you do, be the best at doing that. The factory in which I worked was grim; they had made cans in that building since cans were invented, and I was whisking pallets of cans across the factory floor and depositing those pallets in impossible spaces. Of course, nobody noticed. I, however, had learned a lesson.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.charlesingham.com

- Instagram: https://instagram.com/charles_ingham

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.