We recently had the chance to connect with Christopher Bull and have shared our conversation below.

Christopher, we’re thrilled to have you with us today. Before we jump into your intro and the heart of the interview, let’s start with a bit of an ice breaker: What do the first 90 minutes of your day look like?

The first 90 minutes of my day are among my favorite of any day. As someone who rarely sleeps deeply, I usually wake around 6:30 AM and rise immediately. I switch on the espresso machine, and while it warms, I spend about twenty minutes at the piano. Afterward, I prepare a small cortado and select a record to play while I slowly enjoy my coffee—typically something lyrical and contemplative, such as Chopin’s Nocturnes or Brahms’ Piano Sonatas.

As the coffee winds down, I begin to write. The form this takes depends on my mood and what is unfolding in my life—sometimes it’s journaling, sometimes ruminations, other times aphorisms. Once the writing feels complete, I use the remaining time to make a small dent in whatever book I’m reading; at the moment, it’s Time Regained, the final volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time.

This rhythm sums up the beginning of my day, whether it’s a workday or not. I once thought of it as a routine, but now I regard it more as a ritual—a grounding practice to which I can return if the rest of the day becomes too scattered.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

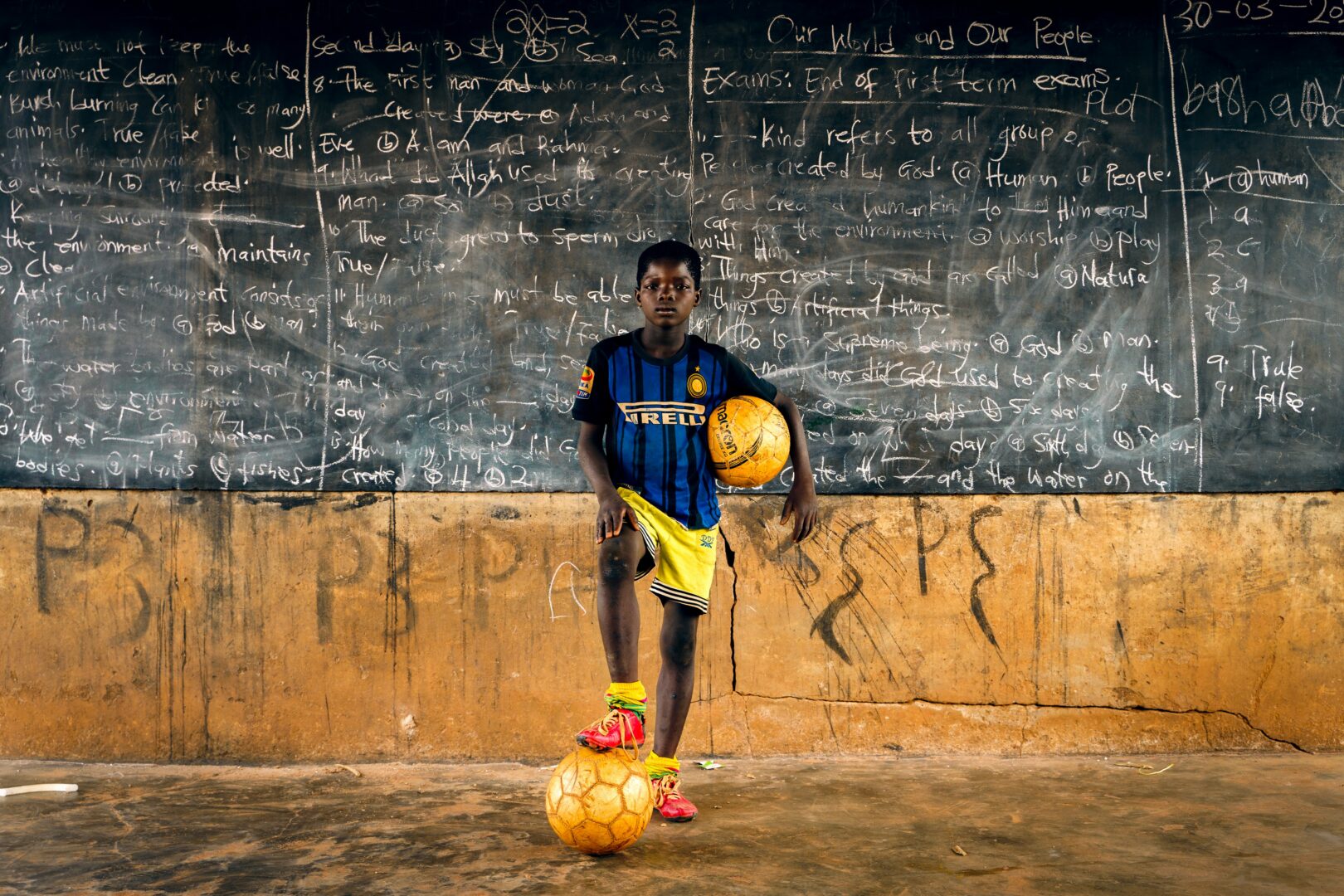

My name is Christopher Bull, and I consider myself both a portrait photographer and a photojournalist. While my artistic direction continues to evolve, the unifying thread is always people—whether through posed or environmental portraiture, photojournalism, travel photography, or even the occasional headshot or studio session.

Most of my work takes shape while traveling, photographing stories and the people I encounter along the way. Because I also work full-time as a pharmacist, I’ve learned to concentrate this practice into focused ten-day stretches. I’ll seek out a story anywhere in the world that deeply captures my interest, devote several days to covering it, and then allow the remaining time to unfold organically—meeting people where they are, listening to their stories, entering their world, and photographing through genuine connection.

What I believe makes my process unique is an unbounded curiosity and a willingness to trust others, which opens space for sincerity and engagement. I often say the camera is secondary—that I am a photographer second, and an inquirer first. In my five years of doing this, I’ve come to see that people can sense this approach, and because of it, they open themselves more freely—allowing photographs to emerge that feel both natural and effortless.

Thanks for sharing that. Would love to go back in time and hear about how your past might have impacted who you are today. Who saw you clearly before you could see yourself?

My Grandma Nancy. Of all the people in my life, she has always been the one who truly saw me—for both my strengths and my weaknesses, for my tendencies, patterns, and peculiarities. But what made her gaze so special was not mere observation, as though she were cataloging traits in a list; instead, she assembled them like pieces of a puzzle, patiently forming a more complete picture of who I was becoming.

Even now, when I speak with her almost every night before bed, I’m struck by the depth of her perception. She has considered each of my characteristics—how they interact, why they shape the way I function, and how they make my experience of the world distinct from anyone else’s. Fernando Pessoa once wrote that “to be understood is to prostitute oneself,” and though I often find truth in that, I would add an exception: on rare occasions, we are fortunate enough to encounter someone with the sensitivity and curiosity to peel back our layers gently, without us even noticing. For me, that rare person has always been my Grandma Nancy.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

In April of 2014, I became sick with what I thought was a lingering cold. After weeks without improvement, I saw a doctor and was diagnosed with mononucleosis. What I thought would be a brief setback stretched into months, then years, and eventually I was diagnosed with CAEBV—chronic mononucleosis, for which there is no cure.

In an instant, everything I had built seemed to collapse. I was studying for my doctorate in Denver, working as an organic chemist, and racing BMX professionally—all of which became impossible. I lost the sport that had defined me, the sharpness of mind on which I depended for school, the stamina to hold a full-time job, and even many of my closest relationships. Daily life became excruciatingly difficult: it could take me hours just to get out of bed, to eat, or to focus long enough to hold a conversation. Any exertion risked weeks of relapse, leaving me bedridden or hospitalized. The question became unavoidable: if my body and mind could no longer sustain my ambitions, what was the point of going on?

Despite this, I managed to finish my doctorate on time in 2016—not through extraordinary strength, but by clinging to the power of routine. The familiar motions of study and work became autopilot, preventing me from disappearing entirely. The illness did not improve, but I began to learn its patterns and flow, to predict flare-ups, and to carve out brief, precious moments of energy. Those fleeting moments of pleasure—small but real—became triumphs in an otherwise bleak landscape.

After graduation, I moved to Pennsylvania to start fresh, but the next three years proved to be some of the darkest of my life. The illness tightened its grip, leaving me a shell of who I once was: no passions, no hobbies, no ability to contribute or connect. By 2019, my former partner and I parted ways, and when she left, she intentionally left behind a small point-and-shoot camera on the dining table. For months it sat untouched. Then one day, almost on a whim, I turned it on. That same day, driven by a sudden impulse, I booked a two-week trip to Pakistan.

In the weeks before the trip, photography consumed me. I devoured everything I could about cameras and the arts, and for the first time in years, I felt sparks of energy through curiosity and anticipation. In Pakistan, despite my limitations, I wandered everywhere, photographing everyone. It was invigorating. I realized that while life would never again be “normal,” it didn’t have to be defined solely by pain and that agony could take a back seat to passion.

One of the first portraits I ever made on that trip—that is to say one of the first portraits I ever made at all, using that little abandoned camera—became the cover image of my published photo book, Owing to Connection, four years later. That photograph marked the beginning of a new life.

So, though I nearly gave up countless times, I did not. My introduction to the arts saved me. Or more truthfully: a simple, forgotten camera planted the seed of spirit and curiosity that grew into a lifeline. Today, I live with a fuller heart, a wilder spirit, and a broader perspective. My suffering expanded my capacity to see, to connect, and to be grateful. I am now grateful for something I wished had never happened.

Alright, so if you are open to it, let’s explore some philosophical questions that touch on your values and worldview. What’s a belief you used to hold tightly but now think was naive or wrong?

1. I once believed that love was enough—that its presence alone could dissolve obstacles, mend incompatibilities, and bend the world to its force. For many years I carried the conviction that love was the ultimate solvent of difficulty. With time, I came to see how fragile that notion was, how naive, and perhaps even how entitled.

2. I also once believed that talent was enough—that natural aptitude would, by its very nature, rise above circumstance, and that those born gifted were destined to surpass others without labor. It took years to realize how misguided that was: talent unguided languishes, while persistence and discipline can transform the ordinary into the extraordinary.

I now see that both of these beliefs dissolve under the same truth: neither love nor talent alone is sovereign. What endures and flourishes does so through the confluence of passion, labor, and circumstance. History is filled with reminders—lovers undone not by the absence of feeling but by the conditions that surrounded them; gifted artists whose brilliance remained unrecognized for want of time, place, or audience; and others, less innately equipped, who through study, imitation, and relentless practice carved something lasting from the raw material of their limitations.

The lesson is humbling: love and talent are forces, but they are not destiny. It is the meeting of inner devotion with outer conditions—the right heart, the right hand, at the right moment—that shapes the course of lives and the creation of art.

Okay, we’ve made it essentially to the end. One last question before you go. When do you feel most at peace?

Peace drifts to me only by degrees, never in its entirety; it is not absolute but relative, a passing calm. My mind is a restless instrument, gathering too much, revisiting, and anticipating — but sometimes, even if very briefly, it capitulates, and that relative peace will exist as I describe here:

It begins on a morning without obligation. The air is cool, clouds spill across the sky like soft paint strokes, and the light falls gently, muted, as if the sun has agreed not to startle me. Somewhere, a reminder of love lingers — a text from a loved one, a voice remembered, plans glowing faintly in the near distance. My cats curl beside me, their weight grounding me to this delicate present. I breathe, trying to release both what has been and what is still to come.

A book waits, its pages thick with sensation, words dissolving into textures and colors that feel dreamed. I carry it with me to the greenest space nearby and let the prose slip me into reverie. Later, I wander, and the world appears almost tender: the rhythm of footsteps, the lucid conversations of branches against the sky, colors interacting with one another with intent. A smile transpires without command, a small recognition that beauty requires no effort.

Soon, the current of thought will return, hurried and importunate. But for now, time loosens and the edges blur. Peace lingers just long enough to be touched before dissolving again into motion.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.chrisbullphoto.com

- Instagram: @chrisbullphoto

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.