We recently had the chance to connect with Claire Campo and have shared our conversation below.

Claire, we’re thrilled to have you with us today. Before we jump into your intro and the heart of the interview, let’s start with a bit of an ice breaker: Who are you learning from right now?

I am learning from my Ancestors. I am learning about their journeys, their pain, their struggles, and their triumphs. I am learning that I have inherited many gifts that surpass space and time. I am learning from the generational trauma, but I am also learning what is mine to heal and hold. We know that all the eggs a woman will carry form in her ovaries while she is a fetus in her mother’s womb. So, when your mother was in your grandmother’s womb, she carried the egg that would become you. This means that a part of you, your mother, and your grandmother all shared the same biological environment. You were exposed to the emotions and experiences of your grandmother even before you were conceived. Knowing that I come from a people whose identity and lifeway and worldview were subjected to genocide, informs how I interact with the world and how the world interacts with me. I am learning from my ancestors’ immense pain and poverty and trauma, but I am also learning that I am their wildest dreams come true. I get to live and tell and speak their stories. Stories that were so wrapped in shame some of them were kept secret for decades. I am learning from the water. From all water. I recently visited the Grand River in Six Nations, Ontario where I am a Mohawk member of the tribe and this river was our life source. I learned so much from the river. I learn from the river in the town I reside in, Tulsa, OK. I am learning that how we treat the water is how we treat our children and our children’s children. I am learning that my ancestors fought to keep alcohol out of our communities. I am learning that my 12 years of sobriety is breaking generational trauma. I am learning that we can heal ourselves, our communities, our lineage- if only we listen.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

I am of Mohawk, Dutch and French descent and a proud member of the Six Nations of the Grand River and I serve as Executive Director of Words of the People, a Native-led nonprofit dedicated to normalizing creative production in Indigenous languages.

My own path to this work is a little different. I was raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma—a long way from my Mohawk community in Ontario. That physical distance meant I didn’t grow up on my ancestral land, and that absence was deeply felt. But what I did carry with me was the language. It became my connection—a kind of homeland that lived in the words, stories, and sounds passed down to me.

That’s why Words of the People means so much to me. We’re not only about preserving language; we’re about fueling it. We support Indigenous artists, writers, and creators making new work right now in their languages—whether it’s through poetry, music, theater, or film. We’re helping build a world where our languages aren’t frozen in time, but alive, and thriving.

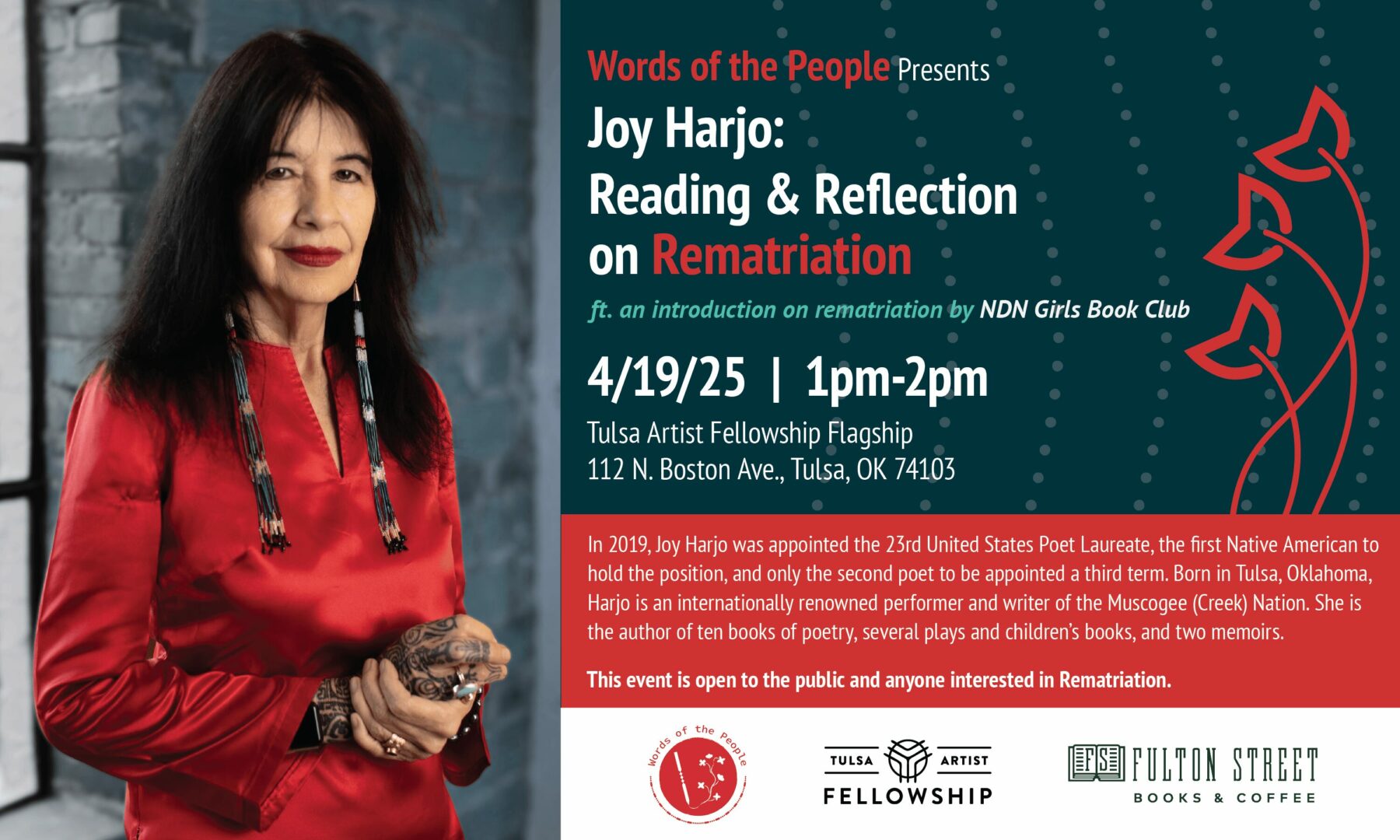

Right now, we’re deepening that work through programs like our Rematriation retreats and support circles, which focus on returning sacred balance and nurturing spaces for our communities. We’re also developing a language curriculum to share with tribes, so that this creative reclamation keeps growing.

At the end of the day, it’s all about keeping our voices strong, present, and beautifully heard—in every way possible.

Amazing, so let’s take a moment to go back in time. What was your earliest memory of feeling powerful?

My earliest powerful moment was the first time I read my poetry. I was 13 years old, in a little coffee shop in downtown Tulsa, and I was shaking with excitement and fear. I had a rough childhood and poetry genuinely saved me, it was my outlet, it was my lifeline. I could talk to the page when I had no one else to talk to. But reading it out loud, discovering Spoken Word, changed my life. I come from a long line of storytellers and oral tradition, and the moment I opened my mouth, it was like I had all my ancestors and aunties and grandmothers in the room with me. I understood what I knew without being able to articulate it when I was younger- the power of a story to heal, to console, to change the air in the room. I felt powerful because I was able to speak to a room of strangers and remind them that we are not so different, that this human life is a mutual experience. It was the transference of emotion, of meaning, of making this group of strangers feel something, together. I knew that there was power in the spoken word. I used that power to heal my younger self, to help guide others to healing, and I’ve never looked back.

What did suffering teach you that success never could?

Suffering taught me how to stay. How to stay with my feelings, my emotions, my own discomfort and shame and fear, and welcome it. Suffering taught me that nothing lasts forever and that I am capable of surfing the waves of grief and heartbreak and loneliness without letting it consume me. It made me confident and brave that no matter what I attempted, whether I ‘succeeded’ in the eyes of the world or not, that I could handle anything that came my way because I learned how to stay with the pain. I learned how to take that pain and transmute it, to make it into something beautiful, to create out of pain is the alchemical gold of true connection. It taught me that the deepest healing often happens not when we escape what hurts, but when we finally sit down in the middle of it and listen to what it has to say.

That practice of staying and listening is the very heart of my work now. It’s how we approach indigenous language creative work at Words of the People—not as a historical artifact to be preserved, but as a living, breathing entity that holds our collective grief, our joy, and our resilience. Suffering taught me that our most profound creative power isn’t born in success, but in the sacred, quiet act of staying present long enough to witness the transformation. Suffering taught me to trust.

Next, maybe we can discuss some of your foundational philosophies and views? What’s a cultural value you protect at all costs?

Rematriation. Rematriation is returning the sacred to the mother, is rebuilding relationships with and in our communities.

It’s more than a word; it’s a commitment to returning to a place of balance. It goes beyond returning the land (repatriation) to restoring Indigenous ways of being, matriarchal principles, and our spiritual and community connections that were often violently suppressed.

For me, this isn’t an abstract idea. Being raised far from my Mohawk territory in Six Nations, I felt the disconnect intensely. I felt like I didn’t fit in, like I didn’t belong, and that absence created in me a longing not just for the land, but for a specific kind of belonging—to the language, to care, to creation and community in a way that doesn’t seek to dominate or extract.

It reminds me of this quote by Lee Maracle, talking about “a time when Turtle Island women had no reason to fear other humans.” Indigenous women were honored and understood for our power in our communities.

Protecting rematriation means creating safe and welcoming spaces where our people, especially our women and Two Spirit relatives, can come together to heal, to speak our languages, to create, and just exist without having to translate our experiences. It’s the foundation of our Rematriation Writing Support Circles, our language work, and our art at Words of the People.

I’ll quote directly from here and leave you with the words of my ancestors

From the Iroquois Confederacy Constitution — Article 44: “The lineal descent of the people of the Five Nations shall run in the female line. Women shall be considered the progenitors of the Nation. They shall own the land and the soil. Men and women shall follow the status of the Mother.”

Okay, so before we go, let’s tackle one more area. Are you doing what you were born to do—or what you were told to do?

I am FINALLY doing what I was born to do! When I began to listen to and learn the language, Kanien’kéha- I was incredibly emotional. The first time I read a poem in public that incorporated Kanien’kéha, people laughed! this was in 2019 when I was living in Atlanta, Georgia and I remember feeling, not ashamed, but embarassed for the people that laughed. Because in that moment I knew my ancestors were proud, even if I was speaking like a toddler and I knew that I didn’t need to be embarassed, I was proud. I was proud of my act of reclaiming and learning my language and no one else needed to understand that journey in that moment. That experience was a tiny fracture in the world I was told to live in—one that asks us to quiet our most authentic selves to fit in. One that had told me I didn’t fit in, I didn’t belong. It cracked everything open.

When I was invited to do this work, I was doing work that was fulfilling but draining, and I did not expect the invitation! It felt less like a career change and more like a homecoming. It was an answer to a call I had been whispering to my entire life without fully realizing it.

I remember my mom saying, “Take care of the language and the language will take care of you.” That has never been more true for me than right now. This work—centering our voices, our stories, our creative spirit in our own languages—isn’t just a job. It is a responsibility and a profound gift. It is the deepest kind of belonging. So yes, this is what I was born to do. It just took me a little while to listen.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://wtpgathering.org

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/wordsofthepeople/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/words-of-the-people

- Other: https://www.newson6.com/story/67f9211f3c2df0b5fac8fa12/words-of-the-people-rematriation-retreat-indigenous-language

Image Credits

Photos by Erica Pretty Eagle, Mariah Gonzalez, Kenna Stimson,

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.