We recently had the chance to connect with Varvàra Fern and have shared our conversation below.

Good morning Varvàra , it’s such a great way to kick off the day – I think our readers will love hearing your stories, experiences and about how you think about life and work. Let’s jump right in? What do you think is misunderstood about your business?

One of the most common misconceptions I hear about being an artist or sculptor is that the profession is entirely about designing and creating the artwork itself—that this makes up 100% of the job.

That couldn’t be further from the truth. When you work as a freelance artist, the actual time spent creating is unfortunately only about 30–40% of the whole picture. The rest is taken up by emails, paperwork, discussions and negotiations with potential clients, and producing self-promotion material—such as Instagram reels or newsletters. It also includes visiting galleries and networking, applying for exhibitions, and so much more.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

My name is Varvàra Fern, and I’m a sculptor who tells emotional stories through surreal, human-like figures. I was born and raised in Moscow, but at twenty I moved to Philadelphia to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts — and I’ve been here ever since, sculpting and growing as an artist.

Sculpture has been with me for as long as I can remember. It started as play, then became a language — a way to speak about things that can’t be said in words. My work blends the classical and the surreal: I love when something looks almost real, but not quite — when it touches something deeper in the subconscious.

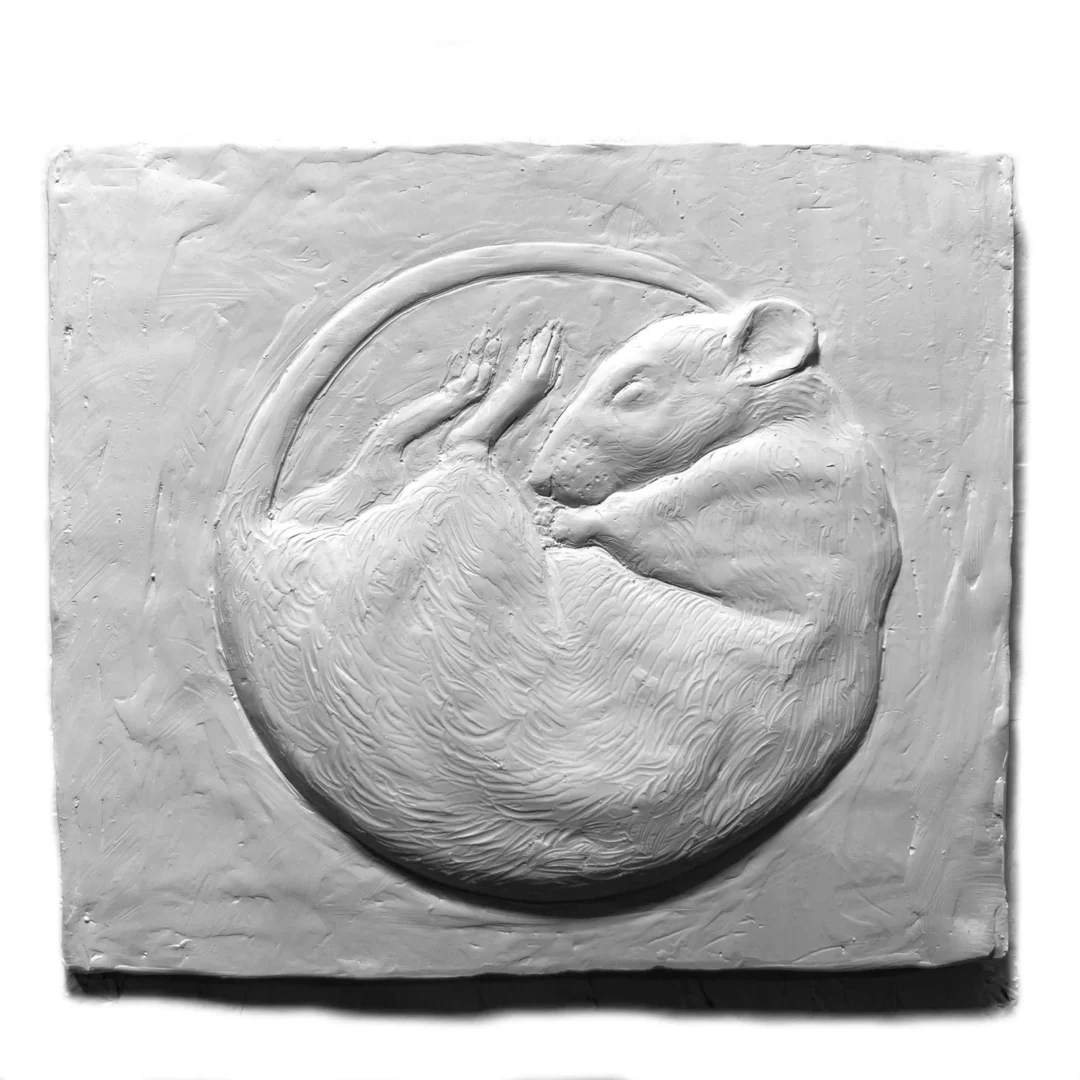

I tend to work in series, because one sculpture is rarely enough to tell a full story. Right now, I’m developing several ongoing series — Travel, Fairy Tales, Bulldogs, and Rats — each with its own emotion and mood. I move between them depending on where I am in life. And as time goes on, new themes and series naturally emerge, growing alongside me and reflecting the changes in my own journey. Right now I am currently working on my own projects such as works for the series that I have listed above, and commissions which are sculptures for other people or/and organizations. One of my favorite recent commissions that I worked on was a fun and surreal 5 foot tall sculpture of a nose for a public art project in Philadelphia.

Great, so let’s dive into your journey a bit more. Who saw you clearly before you could see yourself?

My mother. She was the first to notice that I was always sculpting — constantly shaping something out of oil-based clay and refusing to put it down. I didn’t think much of it at the time; I was a child, and it felt completely natural, almost like breathing. But she was the one who saw that it wasn’t just play — that there was something in it worth nurturing.

She took me to my first ceramics class when I was five, and later found an art high school that offered serious classical training. That became the real beginning of my journey as a sculptor.

She was the first to truly see me — to see what I could become — and she’s been by my side ever since, supporting me through every stage, including the hard ones. I’m endlessly grateful for that.

What have been the defining wounds of your life—and how have you healed them?

Trigger warning: the answer below discusses sexual abuse. Please take care of yourself while reading — skip this section if it may be distressing.

The biggest wound of my life is the sexualized abuse I experienced from my father during childhood. I don’t like the word ‘defining’ — I don’t believe wounds should define a person. To define yourself primarily as “the one who was hurt” is itself part of the trauma. The goal, for me, has always been to shift away from that traumatic definition toward something fuller — “I am an artist, a friend, a fisherman,” and so on. So instead of “defining wound,” I’ll speak of the greatest wound of my life.

The abuse lasted for years throughout my childhood. I don’t remember exactly when it began — I was very small — and it ended around the age of ten. I won’t go into detail; it’s still painful to speak about. Because the abuse wasn’t obvious and because my mind built strong defenses, I didn’t fully understand what had happened for a long time. As a child, I told myself, “Yes, sometimes he does strange things that for some reason make me feel ashamed and confused, but he also seems to love me — he takes me on trips, he kind of supports me. If he does these good things, then he can’t be a monster… right?” Later I realized those gestures weren’t for me at all, but for himself — to keep himself entertained or to show others how “great” he was. Back then, I believed that people who did such things looked like monsters you could recognize instantly. My father didn’t look like that. So for years I pushed away the frightening thoughts — telling myself that maybe I imagined it, maybe it wasn’t what it seemed.

I didn’t face it openly until I was twenty and finally went into therapy. Even then I couldn’t say it out loud — shame held me in a grip so tight I couldn’t speak. I ended up writing it in a message to my therapist, and at the next session she named it plainly: “This is systematic sexualized abuse.” My relationship with my father was already strained after I left Russia, and after that I cut him out of my life completely — blocking him wherever I could.

What followed were two years of hell. I felt utterly broken, as if everything I knew about myself and my family had shattered. I thought there were “normal” people and then there was me — damaged, exposed, different. I thought that everyone could see how “not normal” I was. Slowly, with time, I learned that I was not an anomaly. Most people have survived violence. The problem was never “us” — it was the people who commit abuse. Years were spent gathering the fragments of myself and growing into someone new. I am still doing this work. I continue therapy. I still can’t speak about the details easily — shame and fear of judgment remain — but I know I am on the right path and I am in a far healthier place than I was.

Therapy, the people who have supported me, and my art have all been essential to that healing. Reading this now, some may feel I’m skimming over things or withholding details; perhaps someday I’ll tell more, but not here and not yet — I don’t yet have the strength for that, and this interview is focused on my work as an artist.

I didn’t immediately understand why Little Red Riding Hood appeared in my work. The first piece with her was made for an exhibition, and then I kept returning to the figure. It later became clear how directly that tale helped me process what had happened. In the earliest versions, she walks along a road strewn with wolf skulls — a reflection, I eventually realized, of recurring dreams in which I confronted and killed my father. I lost count of how many times that happened in my dreams, but the number of skulls suggested it was many.

The fairy tale itself became the perfect subject to study and work through. Its Freudian subtext — where the wolf convinces her to remove her clothes, throw them into the fire, and climb naked into his bed — lays bare the story’s underlying themes of violation, abuse and vulnerability. Yet it is also a profoundly feminist tale: in early versions, the wolf devours the girl, but in later tellings she cuts her way out of his belly and kills him, reclaiming her power. Propp’s folkloric interpretation — that being swallowed and later emerging symbolizes not eternal death but rebirth — resonated deeply with me, as it mirrored my own process of confronting the trauma, reclaiming my voice, and transforming pain into strength.

Then I made “Now when I’m stronger than you”, a piece that developed intuitively and whose meaning revealed itself slowly. At a late stage of coloring it, I discovered Ethel Cain’s song “Strangers” and listened to it endlessly; the song’s imagery — of a girl consumed by someone she loves and making him sick when turning in his stomach — echoed my work. Creating that sculpture felt like granting the little defenseless girl inside me a sense of justice and revenge: to return the horror she endured to the person who inflicted it. The piece is bloody because it answers hidden, secret violence with an open, uncompromising image. The girl is now stronger than her abuser and stands on his severed head. Even so, I don’t know what satisfaction such a bloody revenge would actually bring — for a psychopath that might be pleasure; for that little girl it is a tangle of mixed, messy emotions, which is why her face is ambiguous.

Right now I’m working on a sculpture of a dead wolf with its belly torn open and a small child’s hand holding a knife emerging from inside — a symbol of emerging from trauma. Another piece shows a small girl, covered in blood, sitting with a wolf’s pelt over her shoulders and a chamomile flower with a single remaining petal — a sign that childhood and innocence have been wounded, but not entirely destroyed, that a last petal offers a hope for reblooming.

I believe many people, many women, many children have had their own “big bad wolves.” With my art I want to show them they are not alone, to give voice to their pain and, in some way, return that pain to those who caused it. If Little Red Riding Hood can tear herself out of the wolf and go on to heal and live, then that means that I can too. That means that we can.

So a lot of these questions go deep, but if you are open to it, we’ve got a few more questions that we’d love to get your take on. What’s a belief you used to hold tightly but now think was naive or wrong?

A few years ago, I used to believe that rationality should always come first — that the right decisions could only be made through logic, without letting emotions interfere.

Now I see that this belief was really a way to distance myself from feelings that felt too overwhelming to face. Avoiding emotions doesn’t make us stronger; it just hides the tension until it turns into anxiety or even illness.

I’ve learned that relying only on reason might help you survive, but it doesn’t help you truly live. To live fully — with harmony and happiness — you have to listen to both sides of yourself: the rational and the emotional. Finding balance between them is where real strength comes from.

Okay, we’ve made it essentially to the end. One last question before you go. What do you understand deeply that most people don’t?

I’ve come to understand that there’s no such thing as something “everyone knows.”

I think I got enough of that attitude growing up in Russia — when people would act shocked or even judgmental if you admitted you hadn’t read a certain book, seen a certain film, or heard of a certain artist. I’ve seen it less in the U.S., but it still happens sometimes.

I really dislike that reaction — the “How can you not know that?!” kind of tone. To me, that kind of shaming over someone’s lack of knowledge is the highest form of snobbery and passive aggression. If someone doesn’t know something that seems obvious to me, that’s not a reason to judge them — it’s an opportunity to share, to tell, to exchange stories.

We all come from different cultures, backgrounds, and experiences. What feels obvious to one person might be completely foreign to another — and that’s what makes human connection so interesting. Instead of shaming someone for not knowing, we can teach, share, and learn from each other.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.varvarart.com/

- Instagram: @varvara_fern_art

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/varvara.mitrofanova.31/

- Other: Email: [email protected]

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.