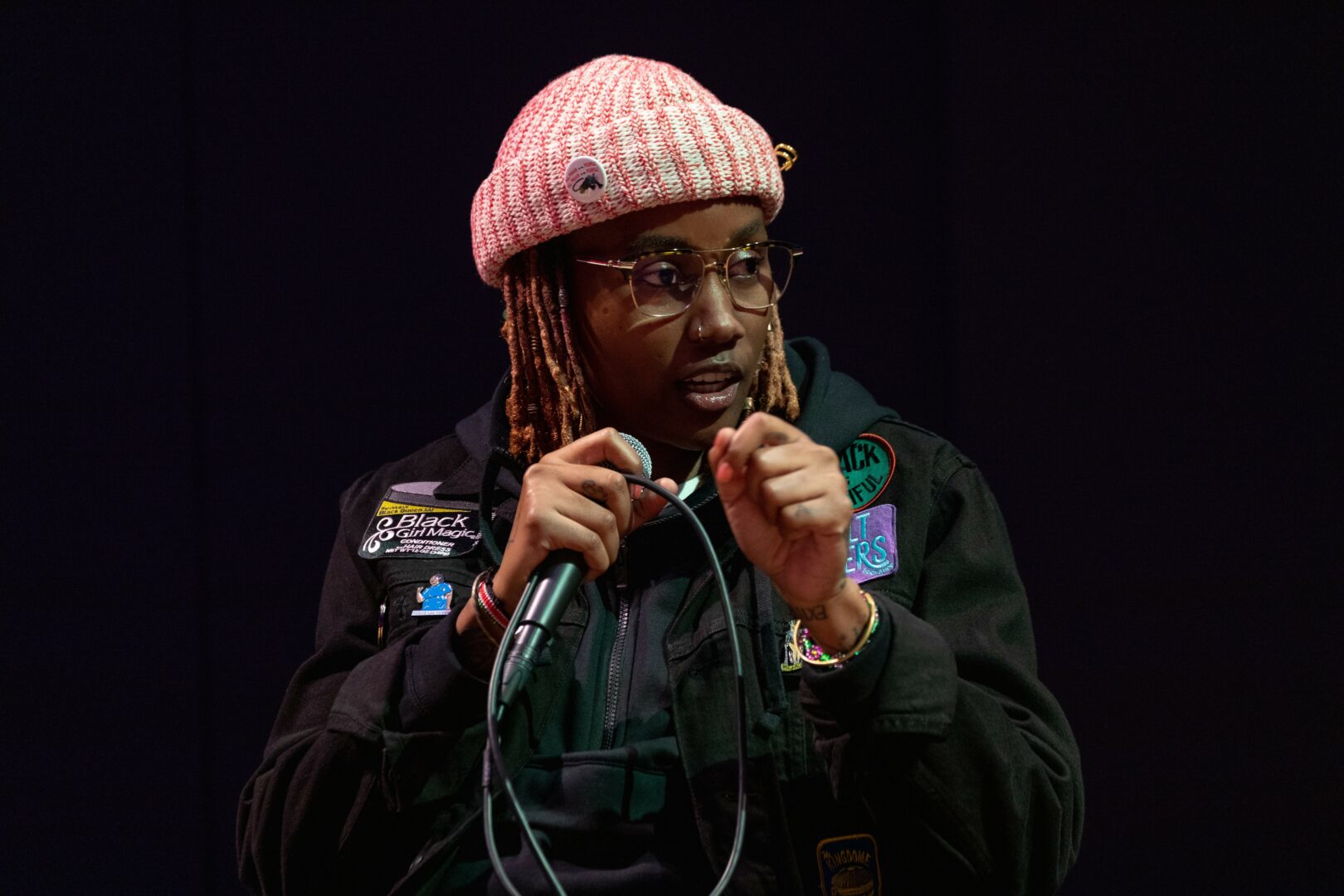

We were lucky to catch up with Aj Musewe recently and have shared our conversation below.

Hi AJ, appreciate you sitting with us today to share your wisdom with our readers. So, let’s start with resilience – where do you get your resilience from?

Resilience is like a legacy for me. I come from a line of women who had the “well, I’ll just do it” gene when things got hard or a solution needed to be created out of thin air. My family comes from Kenya, where I was born, and while technically, I am the only child of a firstborn, by our Luo traditions in my family, I’m also the firstborn of a firstborn. Two of my four middle names come from my great-grandmother, who carved her own path when she went against her family’s wishes. She was so sure in her journey that when she was threatened with being kicked out of the family, she took her five children and lived under a tree until she got housing. That headstrong woman then gave birth to my grandmother, who is equally stubborn and tenacious when it comes to her own accomplishments. When the HIV/AIDS virus hit Kenya, my tribe was pummeled with death, wiping out a whole generation and leaving orphaned children and grandparents too elderly to take good care of them. My gran, seeing the devastation of her home, gathered the able-bodied women, made porridge from the extra money sent to her by her kids, and went about checking on orphans to make sure they had something to eat and assess their health.

When speaking of my mom’s resilience, that’s really where I get a burst of pride. We got to the States in the mid-90s and ended up in an awful place. My mom’s ex-husband was the textbook definition of an abusive spouse, and my mom was in a country where the systems and way of life were so drastically different than what she had been used to for her whole life with a young child. With her mind made up that I wouldn’t be raised in that environment, she looked for resources, kept her wits about her and got us out of California and into a shelter system in Seattle. A month later, we were in transitional housing, and two months after that, we had permanent housing and were entirely out of the shelter system. A year later, she was one of the early employees of a budding nonprofit organization called The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Talk about boss moves. By the early 2000s, my mom lost her baby sister and baby brother to the virus, and when she went home for the first time in 2003 as an employee with the Gates Foundation, she got a first-hand understanding of what my gran had been trying to explain to her over the years. My mom knew more needed to be done, and soon, she left the Gates, deciding to go back to school, earning her BA in Public Health and a Master’s degree in Public Administration as a recipient of the prestigious Truman Scholarship from the University of Washington.

In the last two decades, my mom has bucked the patriarchal systems of our tribe and, on her terms, built on the legacy started by my grandmother, building two schools, a health care center, a daycare center, and a library. She has also educated more than 300 kids through high school and brought jobs to her village, where she employs almost 1,000 local workers, teachers, doctors, and more. Having her as a living example of what to do with life’s lemons gives me a blueprint on how to work for your community to ensure they have all the resources to match any opportunity that comes their way.

Appreciate the insights and wisdom. Before we dig deeper and ask you about the skills that matter and more, maybe you can tell our readers about yourself?

I started a facilitated history initiative called With Reverence Co-op (WRC) as a way to support today’s history makers through intentional, informed movement and sustainable community care. Grounded in compassion and curiosity, its mission is to build community-centered programs that spotlight historical truths, contextualize history for the modern era, and create investment models of tangible care for the current generation of activists. I am the Groundskeeper of WRC, and I see my role as planting seeds of exploration, then watering and nurturing the curiosity that follows through curated dynamic storytelling sessions filled with scholastic mischief.

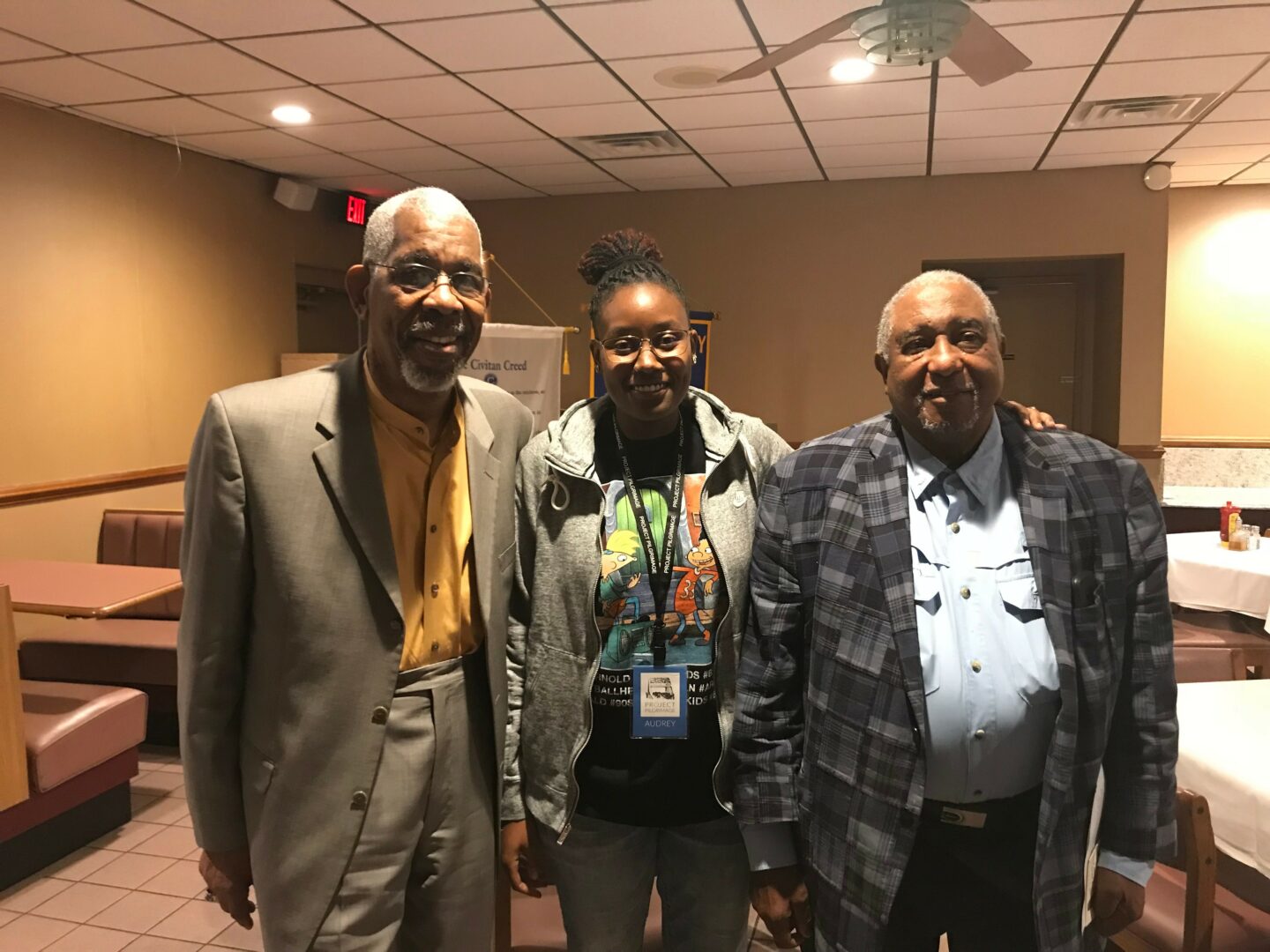

In 2017, I traveled to the South to learn and experience physical moments of history I had only read about in school. From Greenwood and Jackson, MS, to Montgomery and Birmingham, AL, I got a tangible lesson on how working together can literally change history. Those lessons stuck with me, and over the next few years, I worked to figure out how to honor the history of Black community care. Official and unofficial co-op models were intrinsic to progressive social movements and core marginalized communities.

In the United States, before slavery, Indigenous people were always stewards of the land. After the implementation of race-based slavery, enslaved men, women, and children were taken from West Africa and forced to clear land to build the sugar plantations in the Caribbean, the rice fields in the Carolinas, and the cotton fields all over the South that fueled an economy that caused the Civil War. During Reconstruction, Black people were promised “40 acres and a mule”, a dream that devolved into oppressive sharecropping practices that kept land ownership and, with it, the opportunity to build equity and generational wealth further out of reach.

The Civil Rights Movement utilized restaurants like Dooky Chase in New Orleans, Paschal’s Restaurant in Atlanta, and Ben’s Chili Bowl in D.C., while “shoebox lunches” offered fewer obstacles for families traveling across the Jim Crow South. Women like Georgia Gilmore started groups like Club From Nowhere (CFN), a stealthy crew of Black women who sold food and raised money for the entire 381 days of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Community events like the CFN fish fries to fund and maintain the Movement. Many were organized by Black-founded co-ops like the Freedom Quilting Bee in Alerta, AL, to the personal inspiration of this initiative, the Freedom Farm Co-op in Sunflower County, MS, founded by one of the most outstanding community organizers, the activist and visionary, Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer.

Mrs. Hamer and many Black women like her had a fearless and deep love for their communities. That love spurred Mrs. Hamer to create the Freedom Farm Cooperative, which fed, educated, housed, and sustained the residents of her home in Sunflower County, MS. My deep admiration for Mrs. Hamer and my love for history, storytelling, and my community drove me to create the With Reverence Co-op (WRC). Along with the name, the ethos of this initiative is, in part, a love letter to those who got us to this point, a way to honor the past, revere those who laid the foundation, take that flame, and move it forward.

At this time, WRC is partnering with Samuel Adaramola on a podcast called Papers For My Acres, a show focusing on history, culture, and the shared experience of the diaspora. There’s a lot of internal strife in the diaspora caused by a lack of information and a lack of understanding. The hope is that me and Sam, as two first-generation immigrant kids who spent most of our lives in the States and have a deep love and respect for Black American culture and contributions, can create a project that allows us to show that our differences make us unique but also can bring us all together. We have a fantastic show with some epic guests that I’m really proud to be a part of, and I can’t help but be excited to get more ears tuning in as we share our pilot season.

If you had to pick three qualities that are most important to develop, which three would you say matter most?

One quality that has had the most impact on me is my nurtured curiosity. My mom has always made room for me to ask questions, and that inquisitive nature has had a significant effect on how I’ve moved through the different jobs I’ve held in my life. It has lessened frustrations when I didn’t get something on the first try and has allowed me to create friendships and connections just by being curious about how someone did a task or even moved up the ladder to their job position. Curiosity has allowed me to let go of perfectionism, creating space for me to enjoy being in the trenches when starting something new and getting dirty as I wade through those initial experiences.

Another quality I lean on is the ability to pause, observe, and listen. There are so many lessons out in the world that we miss out on because we are moving too fast to pause and listen to those who hold a lot of wisdom. It’s the everyday person we may not think to listen to who holds a wealth of knowledge but has been shunned by the typical hierarchy. When you treat those around you as equals, coupled with curiosity, you learn a lot about how the world works.

The final one is more of a three-for-one. I was raised with three simple rules for life: Do the right thing, especially when no one is looking. Try and live a life of purpose and be kind. Anything that I was dealing with in my professional or personal life fell into one of those buckets. In my career, it meant not taking shortcuts and doing my tasks to the best of my ability. These foundational rules helped me produce work that I was always proud of, working hard while on the clock, not just when my boss was in the building. Greeting support staff and delivery folks the same way I would greet a client or some other important person coming into the office.

All these qualities help me streamline the person I am no matter where I go. That gives me the freedom to focus on the task at hand, making me more successful even if the work is hard. At the end of the day, when I lay my head down, I want to be proud of the way I have conducted myself in my professional and personal life, leaving those I engaged with that day with a positive feeling. I advise those on any journey of self-discovery or a new career to figure out how they want to bring themselves to those spaces. What type of impression do you want to leave behind? Would you like to work with yourself? How can you channel your natural soft skills into a path moving you forward? What is needed for you to accomplish that? Those self-reflective questions can impact how you traverse any space you are in.

If you knew you only had a decade of life left, how would you spend that decade?

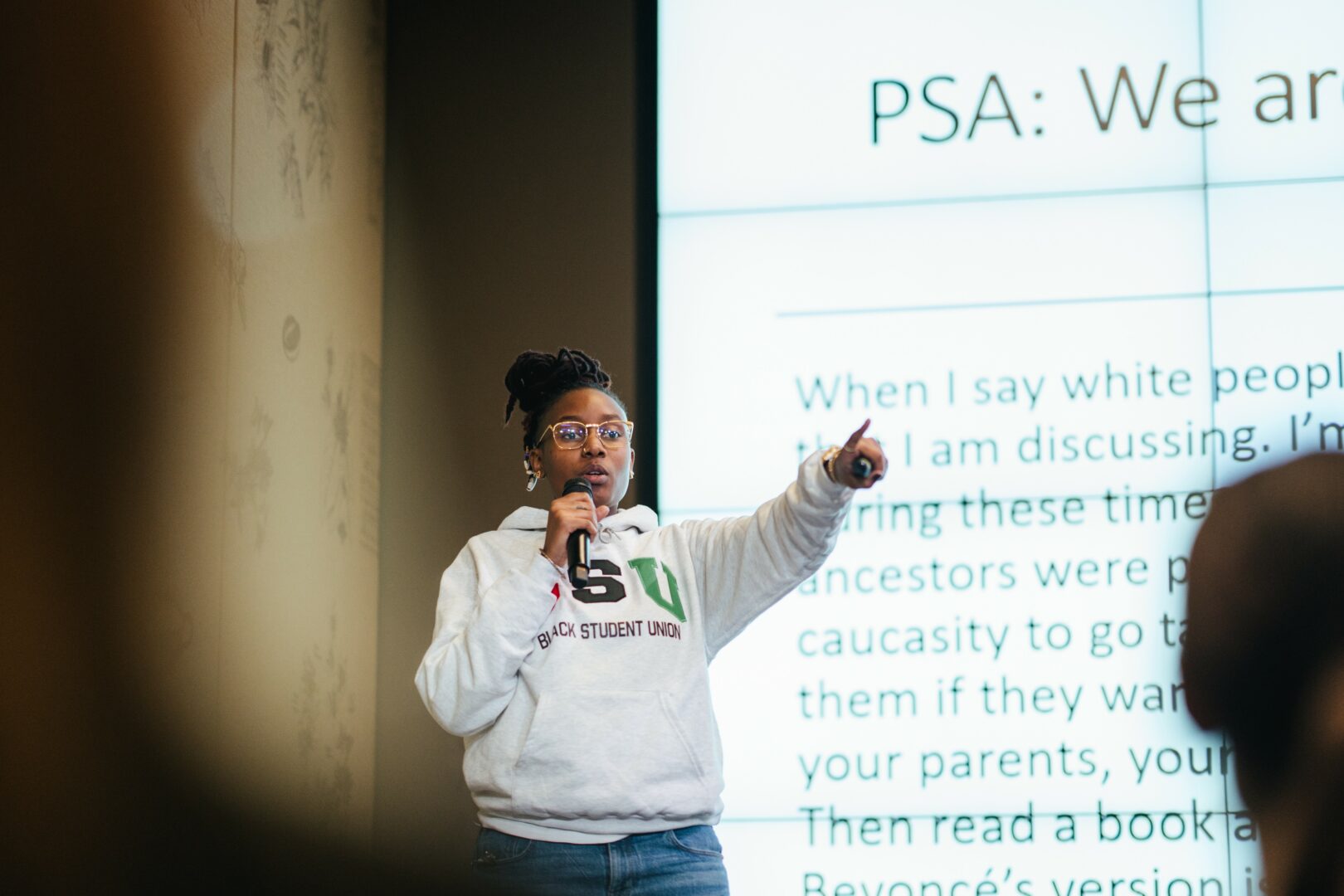

My current challenge with the work I do is the fatigue around learning about history and how that affects how we function today. With how heavy the last few years have been, it’s understandable for folks to be overwhelmed, and coupled with how biased and incomplete our schooling was, getting factual history that centers on Black achievements can feel jarring for the general public. The lack of attention to an honest retelling of the contribution of Black and Brown ancestors, along with the whitewashing of general history, can make anyone feel like righting that ship is too monumental of a task.

One aspect of that challenge is getting more white folks to come to the table and face the fear of “messing up” and the discomfort that comes with being made aware of how they play into larger social narratives. Yes, I know that you don’t own enslaved people now; I’m not even asking you to look into your ancestral past to find out if you had slave-owning ancestors. What I want is for you to be an active participant in undoing the social inequities at play due to the way this country was set up.

Living in the Pacific Northwest, I deal with a covert racism that can be hard to decipher. In my lectures and sessions over the last five years, I’ve found that “well-meaning” white folks have a really challenging time when they realize they have done something bigoted or even downright racist. They want to share all the books they have read and all the activism they have engaged in rather than pause, acknowledge the harm they caused, and then work to do better. The conversations turn into a downward spiral, focusing on how even a gentle call out feels offensive to them.

Another challenge comes with talking to the elders who have survived Jim Crow to hear their stories and the lessons they have learned without traumatizing them all over again. A lot of our elders didn’t go to therapy for various reasons, so silence and putting that trauma in a box in the back of their mental closet was the best way for them to survive and move forward. Those experiences and stories are so crucial to how we build a fuller picture to enhance the academic narratives we are flooded with. Dr. King’s contributions are legendary in the fight for civil rights; there is no denying that at all. A respectful but, as a community educator who wants to honor women like Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, an activist who learned at age 44 that she had the right to vote and soon became one of the oldest Field Secretaries for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the everyday Black people like her were the ones who made Dr. King’s vision possible. These foot soldiers were the ones who boycotted, marched, and faced fire hoses and police dogs in the tens of thousands across the Delta. They lost their jobs and their homes for the right to register to vote and made up the many nameless faces in the crowds of these significant historical moments that center the greats mentioned during Black History Month.

I hope to keep working on ways to get more people, not just Black and white, to want to know more about those who challenged this country to live up to its founding documents and then put those lessons into practice.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.withreverence.org

- Instagram: @ajandthebeanies

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ajmusewe/

- Other: Our podcast Papers For My Acres can be found anywhere you listen to your favorite shows!

Image Credits

Personal photo credit: Sayed Alamy

photo 5: Chantal Evans

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.