We recently connected with Amer Abukhalaf and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Amer, really happy you were able to join us today and we’re looking forward to sharing your story and insights with our readers. Let’s start with the heart of it all – purpose. How did you find your purpose?

I found my purpose by observing the profound and lasting impact disasters have on both the physical environment and the people who live in it—particularly those in under-served communities. Early in my academic and professional journey, I was drawn to questions not just about how we rebuild after disasters, but for whom we rebuild, and what kind of recovery we prioritize.

My training in construction and real estate development naturally gave me the tools to analyze housing and infrastructure. But over time, I became increasingly aware of the invisible toll disasters take on mental health—especially when communities are left in substandard living conditions long after the headlines fade. That realization led me to work across disciplines and connect with public health researchers, eventually becoming a faculty scholar with the Clemson University School of Health Research.

My purpose crystallized when I saw how structural decisions—about housing, planning, and investment—either alleviate or deepen human suffering after a crisis. I knew I wanted my research to bridge those gaps, not just to understand what happens after disasters, but to advocate for more just, responsive, and resilient systems of recovery.

Appreciate the insights and wisdom. Before we dig deeper and ask you about the skills that matter and more, maybe you can tell our readers about yourself?

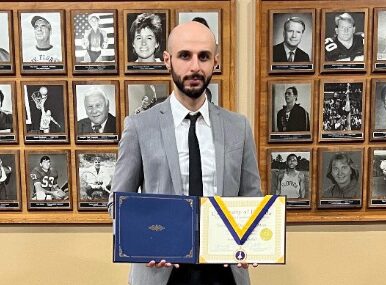

I’m an assistant professor at the Nieri Department of Construction and Real Estate Development at Clemson University, and a faculty scholar at the Clemson University School of Health Research. My work focuses on disaster management and response—specifically, how the damage to housing and infrastructure from disasters impacts the mental health and long-term wellbeing of under-served communities.

What excites me most about this work is its urgency and humanity. Disasters aren’t just technical failures—they expose deep inequalities in how we build, plan, and recover. I’m particularly passionate about making sure the voices and experiences of those most affected by these events—often communities that are already marginalized—inform how we rebuild and how we prepare for the next crisis.

One of the most rewarding moments in my career so far was when an article I published with Science X on Phys.org was republished by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction on their platform, PreventionWeb. That recognition affirmed that this research has global relevance and can help shape policy and practice at an international level.

At its core, my work is about bridging gaps—between engineering and public health, between recovery and equity, and between policy and lived experience. I want to help create systems of disaster response that are not just faster or more efficient, but also more just.

There is so much advice out there about all the different skills and qualities folks need to develop in order to succeed in today’s highly competitive environment and often it can feel overwhelming. So, if we had to break it down to just the three that matter most, which three skills or qualities would you focus on?

Looking back, I would say that empathy, resilience, and interdisciplinary thinking have shaped my journey more than anything else.

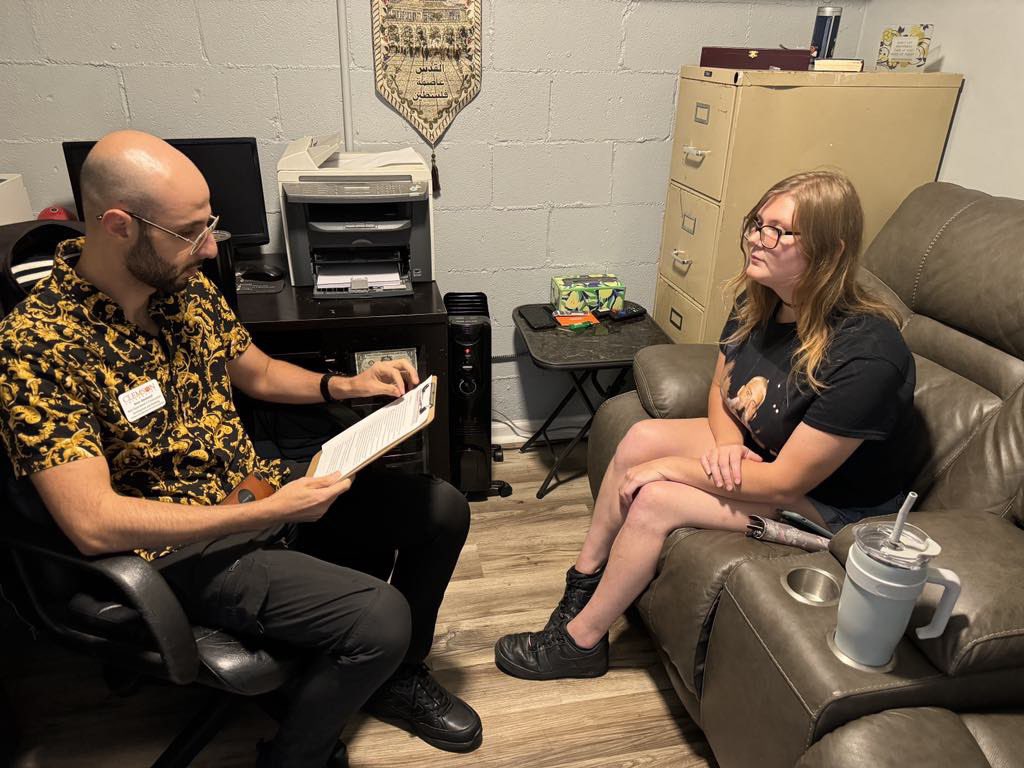

Empathy was what first pulled me into this work. You can study buildings, maps, or infrastructure, but if you can’t connect with the lived experiences of the people those systems are meant to serve, then your work risks being hollow. I started to see the hidden suffering—people stuck in damaged homes, families navigating trauma in silence—and I knew I couldn’t just study structures. I had to study lives. My advice: stay close to the human stories. Listen deeply. Let empathy guide your questions, not just your answers.

Resilience wasn’t just a research topic—it became a personal lesson. Like many in academia or in advocacy work, I’ve faced moments of doubt, isolation, and feeling like I wasn’t being heard. But each time, I reminded myself of why I do this—to make things better for people who often go unseen. So to those early in their journey: don’t expect a straight line. Purpose is not always loud. Sometimes it shows up quietly, in your persistence.

And finally, interdisciplinary thinking has been a superpower. The problems we’re facing don’t fit neatly into one box. I had to learn to speak the language of engineers, public health experts, policymakers, and community organizers. It made me a better researcher and a better advocate. If you’re just starting out, be curious beyond your field. Ask hard questions. Build bridges. The solutions we need won’t come from one discipline alone. What has mattered most in my journey wasn’t just what I knew—but how willing I was to keep learning, listening, and leading with purpose.

Is there a particular challenge you are currently facing?

One of the biggest challenges I’m facing right now is navigating the gap between research and real-world implementation—especially when it comes to translating findings into meaningful policy change for under-served communities impacted by disasters.

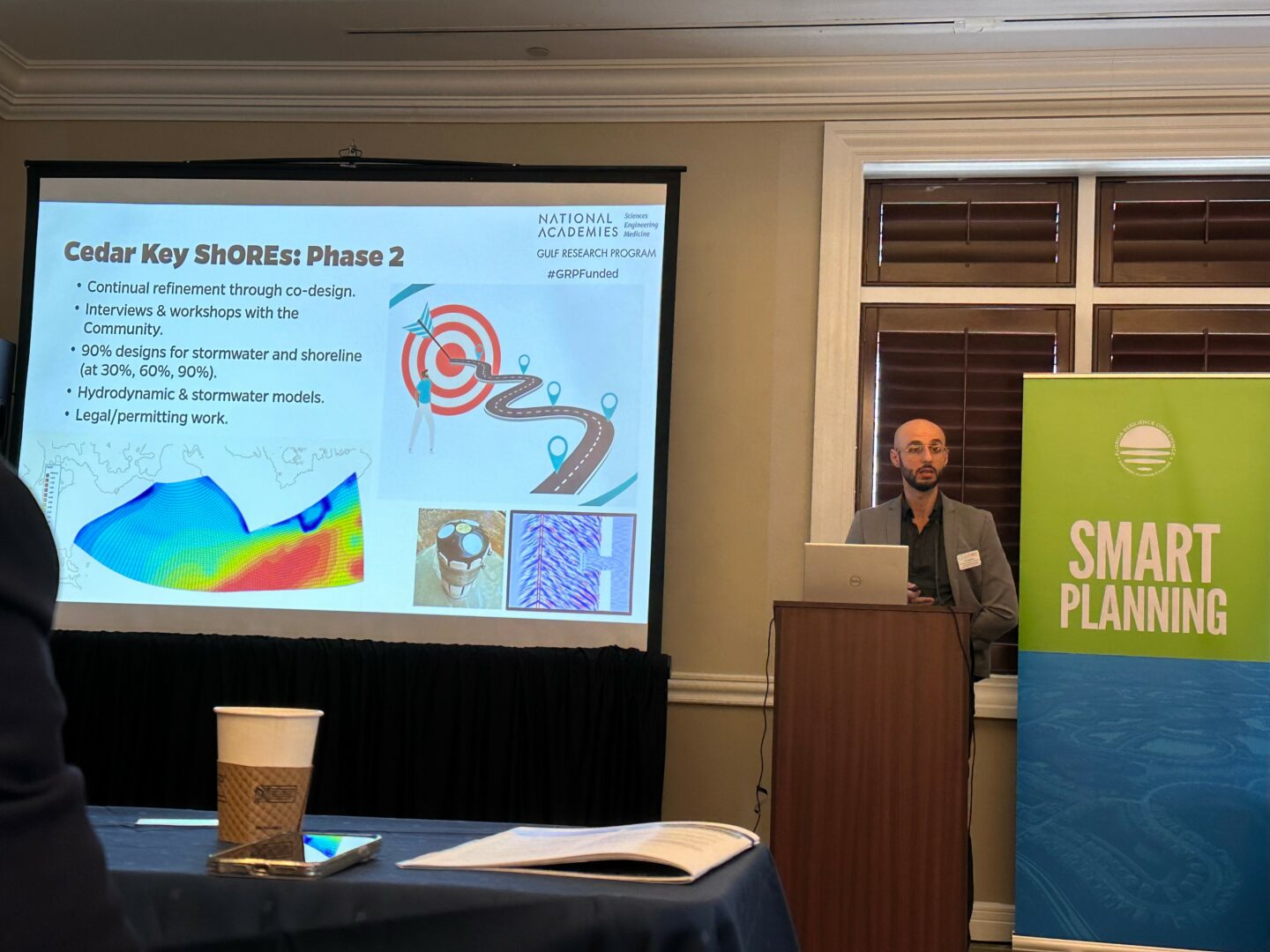

It’s one thing to publish in academic journals or speak at conferences, but it’s another to ensure that the knowledge actually reaches the people making decisions on housing recovery, mental health services, or infrastructure investment. Too often, those most affected by disasters are left out of the conversations that determine their futures. That disconnect is something I think about constantly.

To address this, I’m working to build stronger partnerships—with local communities, government agencies, and interdisciplinary teams—so that my research doesn’t just sit on a shelf. I’m also investing more time in public scholarship, through platforms like Phys.org and PreventionWeb, to communicate findings in accessible, actionable ways. And I’m learning to listen more—to what communities say they need, rather than what we assume they need.

It’s a long road, but I believe that meaningful change happens when research becomes a bridge, not a barrier. That’s the challenge I’m committed to overcoming.

At last, I want to extend my sincere gratitude to the Nieri Department of Construction and Real Estate Development at Clemson University. The support I’ve received from my department has been invaluable to the work I do. In a time when researchers across the U.S. are facing increasing political and institutional challenges, finding a supportive academic home is not something I take for granted. I’m proud to be part of a team that not only advances critical research across disciplines but also remains deeply committed to delivering one of the top-rated student learning experiences in the country. Being surrounded by colleagues who value both innovation and impact makes all the difference—and I’m truly grateful for that.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.clemson.edu/health-research/faculty/faculty-scholars/abukhalaf.html

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/amer-hamad-issa-abukhalaf-71320275/

- Twitter: @AbukhalafAmer

- Other: https://www.clemson.edu/caac/about/facultybio.html?id=7499

Image Credits

Dr. Amer Abukhalaf

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.