We were lucky to catch up with Andreas Troeger recently and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Andreas, really happy you were able to join us today and we’re looking forward to sharing your story and insights with our readers. Let’s start with the heart of it all – purpose. How did you find your purpose?

I didn’t find it. I built it—out of broken parts, sidetracks, and refusal.

I grew up in working-class Munich during the ‘60s and ‘70s. My mother made hat molds, my father worked as a precision mechanic for a local camera company—so our house was littered with film and photo gear. At seven, I got my hands on a Normal-8 camera from AGFA, spliced 16mm film down to 8mm, and shot my first sci-fi epic with action figures, English UFO merch, and a gang of willing friends. I was hooked—not just on images, but on the machinery behind them. I learned to cut film with a blade and glue, then screened it for whoever would watch.

At 14, I joined a rock band as lead guitarist. Got kicked out because I couldn’t sing. No big loss—I already knew I was chasing something else. But when my father died suddenly, I shelved art school plans to support the family. That detour led me to become a mainframe computer analyst. The job paid. The job drained. Meanwhile, I was sneaking into mosh pits and rock shows with a fake press pass, hustling to get good shots, never thinking of myself as a “real” photographer.

One day I dropped both my girlfriend (who was cheating) and the job. With help from friends, I applied to film school in Munich. That was the reset. I fell deep into the underground performance art scene—filming, photographing, and slowly stitching together a new identity. A doc I made about paramedics earned me the German Short Film Award, followed by an even darker one about morgue workers. These weren’t stories the mainstream wanted. That made them worth telling.

A scholarship took me to NYU in ’92. That’s where I met Nam June Paik—father of video art—and became his cameraman and editor. Through him, I was pulled into the chaotic heart of New York’s experimental art world, collaborating with radical choreographers, painters, and filmmakers.

By the mid-‘90s, the internet hit—and I saw it as another blank canvas. I co-founded Name-Space, an activist project to open up domain names beyond the corporate gatekeepers. We were trying to build a freer internet. We were ahead of our time. Bureaucracy buried the project, but the scars stayed.

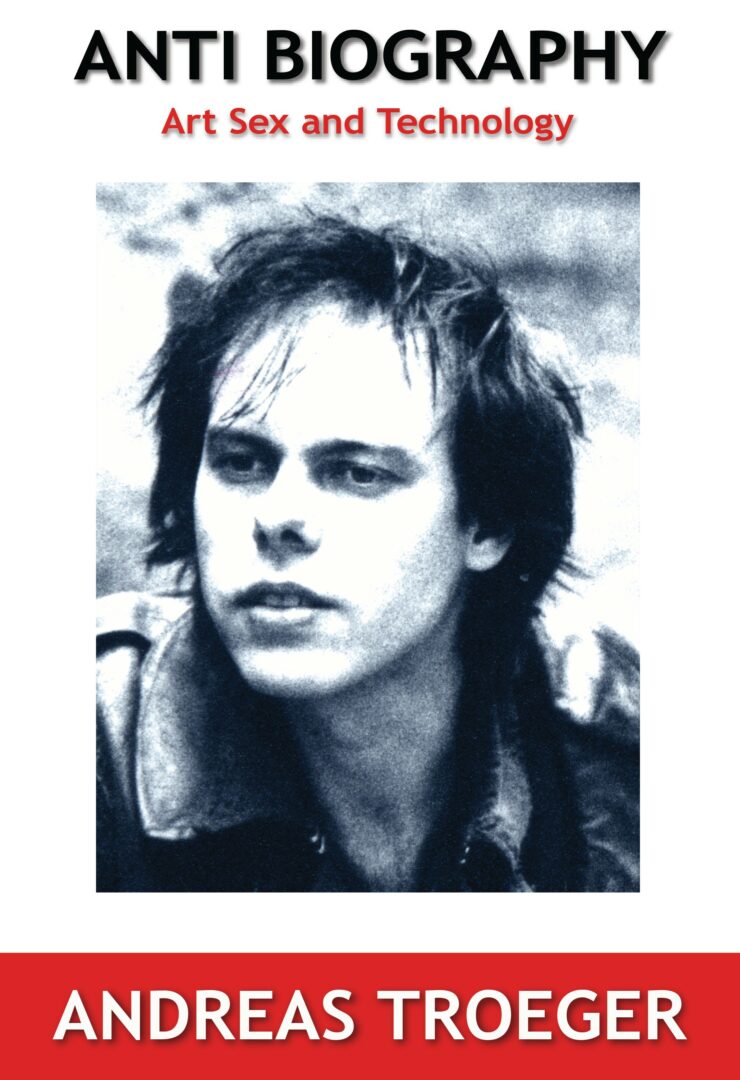

So I turned back to film. Kill the Artist was my middle finger to censorship—featuring raw, unfiltered voices like Richard Kern, Nick Zedd, and Jörg Buttgereit. Around that time, I also started writing the Anti Biography series—a rejection of polished narratives. No tidy arcs. Just fragments and reality.

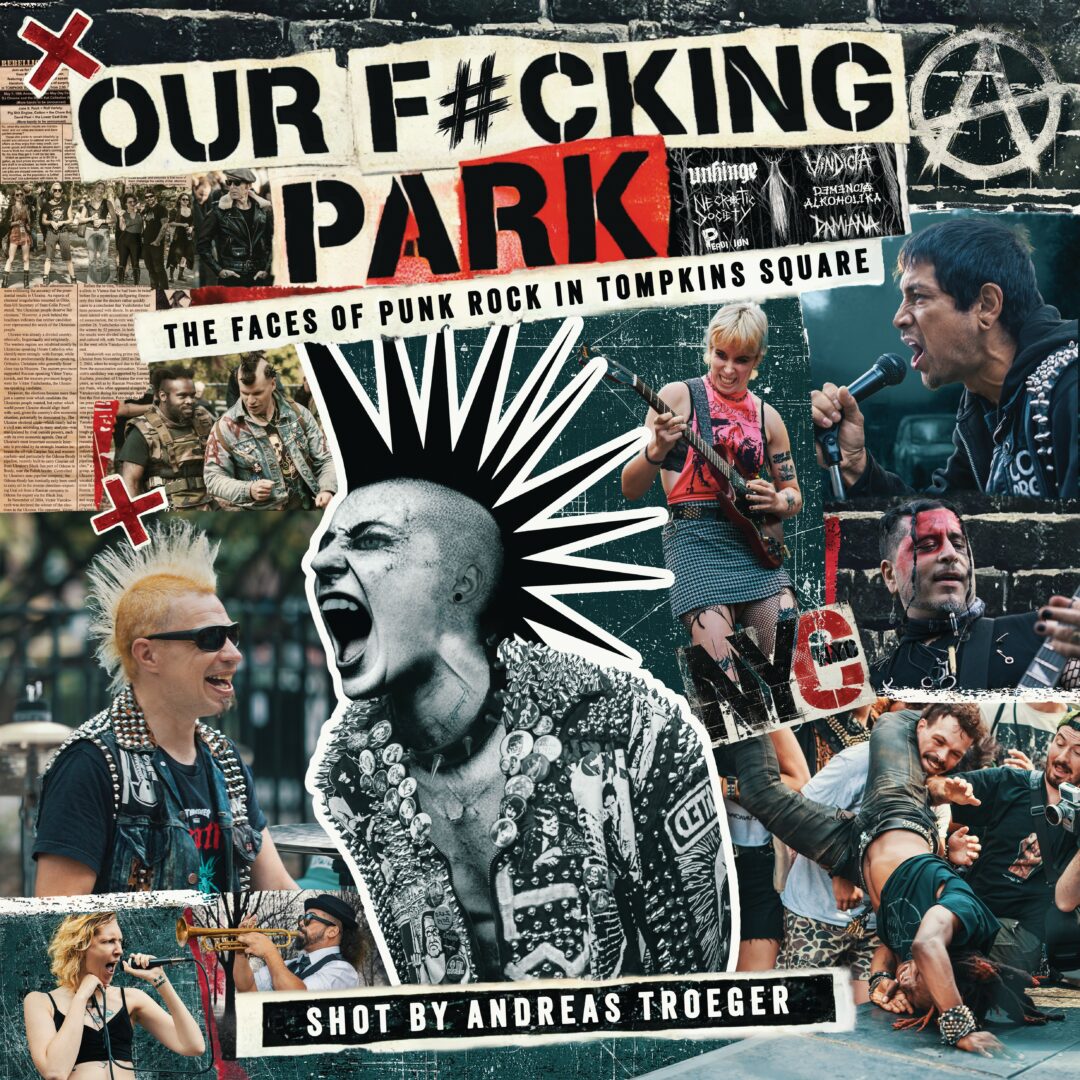

From 2019 to 2024, I shot the punk revival in Tompkins Square Park. Hundreds of shows. No permits. No filters. That became OUR F#CKING PARK—a photo book that captures the final bastion of unpolished, collective chaos in NYC.

Purpose wasn’t a goal—it was a side effect of refusing to conform.

Thanks for sharing that. So, before we get any further into our conversation, can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what you’re working on?

I move between images and sound. My work lives where photography, music, and underground culture collide—and none of it is sanitized.

The musicians that interest me have circled back to their roots: gritty, analog hardcore rock & roll. No polish. No auto-tune. Just amps, distortion, and sweat. No label, no middleman—just direct transmission.

As a photographer, I stay close to chaos. My lens isn’t here to flatter. It’s here to expose. I focus on unfiltered human moments: punks in the park, artists on the fringe, strangers in resistance. OUR F#CKING PARK was the latest product of that—the culmination of five years shooting the punk scene in Tompkins Square Park. It’s not nostalgia. It’s survival. The book is out now—on Amazon, in local bookstores (Village Works in NYC), and museum shops (Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space). It’s loud, honest, and full of dirt under the nails.

Right now, I’m working on a 2025 photo book of hardcore concerts in Tompkins Square Park, along with the next installment of my Anti Biography series—titled No Survivors. It’s the rawest yet. No fake arcs. No triumphs. Just fragmented memory, wreckage, and the strange beauty of still being here. The first two books in the series tore away the myth of the hero’s journey—this one sets fire to the wreckage.

The brand? If you want to call it that—it’s resistance to polish. A refusal to filter. Whether it’s film, photos, books, or music, the core is the same: truth that hurts a little. Truth that doesn’t sell well. But truth that sticks.

Looking back, what do you think were the three qualities, skills, or areas of knowledge that were most impactful in your journey? What advice do you have for folks who are early in their journey in terms of how they can best develop or improve on these?

Early creative obsession, resilience, and building raw, honest connections—those are the three anchors of everything I’ve done.

Creative obsession started young. I was slicing 8mm film, using stop-motion to blow up plastic tanks with firecrackers. This wasn’t just about fun—it was about escape. My father was an epileptic with a violent temper who weaponized discipline and humiliation. Filmmaking was a lifeline. The act of creation gave me control when nothing else did. It taught me that invention isn’t always born in a studio—sometimes it’s born from fear and necessity.

Resilience came as a survival skill. I detoured hard—working corporate tech, living a double life as a programmer by day, artist by night. Anti Biography is laced with near-collapse moments: being cheated on, scraping by, juggling paramedic shifts and underground theater, sabotaging a life I hated just to force a new one to emerge. But I didn’t stop. Not after losing film reels, not after getting rejected, not after lovers left or projects died. The trick isn’t toughness—it’s persistence without permission.

And connection? That’s your fuel. Not networking—real connection. I found performance artists, punks, dancers—people living on the edge and making meaning from it. I shot their shows, lit their sets, built trust in dark rooms and underground clubs. These bonds helped me get into film school, win awards, and co-create work that meant something. Without community, art doesn’t survive—it just echoes.

Advice for the next generation? Start before you’re ready. Use what you’ve got. A cheap camera is better than a perfect plan. Learn to live with rejection—it’s not a wall, it’s just noise. Stay close to people who challenge you, not flatter you. And never underestimate the power of documenting your life as it is—ugly, wild, fragmented. That’s where truth lives.

Do you think it’s better to go all in on our strengths or to try to be more well-rounded by investing effort on improving areas you aren’t as strong in?

Of course, one needs to discover their strength and unique ability and focus on that skill. As a filmmaker and photographer, it’s important to understand the entire palette of the craft. The more you know about all aspects of expertise, the better you can direct and communicate with specialists like colorists or sound designers to clearly explain your creative vision.

When I was shooting and directing “Lifepak”—the German short film that won me the German Short Film Award—my background as a paramedic in Germany played a critical role. I had spent about two years in the field, and that firsthand experience laid the foundation for the film’s authenticity. I knew exactly what the paramedics were going to do, so my camera moves weren’t reactive—they were premeditated. I had the sequence of actions mapped out in my head. That allowed me to position myself precisely to capture the intensity of the moment, especially during a scene of resuscitation in a bedroom, with the patient’s entire family watching as three paramedics worked to revive the patient. That level of realism is what made the film resonate.

Being a musician and guitarist also helps immensely when photographing musicians during live performances. Understanding chord progressions, knowing when a solo is about to drop, and anticipating lighting changes gives me the edge. It puts me in the right spot at the right time to get the shot.

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.TechnologyArtist.art

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/TechnologyArtist

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TechnologyArtist

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/atroeger/

- Twitter: https://x.com/TekArtist

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@technologyartist8917

- Other: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0F32NFWXB (Photo Book)

https://www.amazon.com/stores/author/B0DVMCPBWT?ccs_id=22ca1ff1-07ac-42b5-8c56-03d3779a4111 (Author Page Amazon)

Image Credits

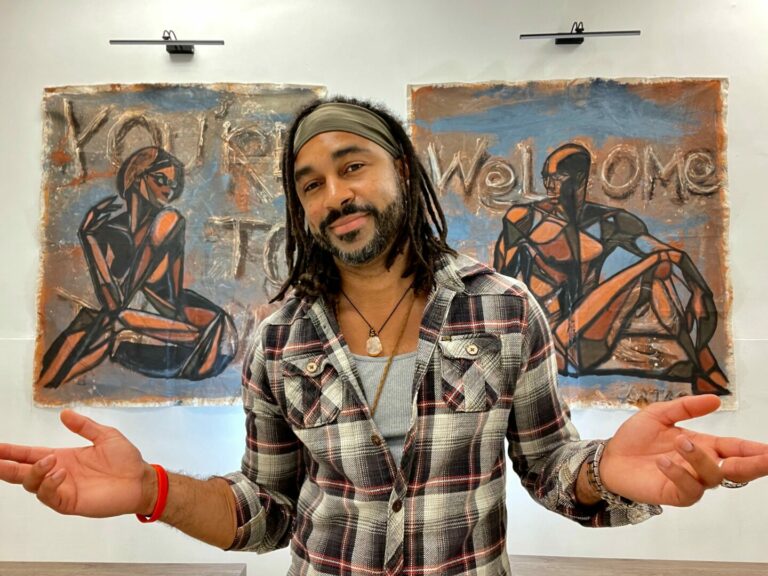

Photo of Andreas Troeger by Richard Lerner

All other photographs and images by Andreas Troeger

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.