We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Anny Fenton. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Anny below.

Anny, so good to have you with us today. We’ve always been impressed with folks who have a very clear sense of purpose and so maybe we can jump right in and talk about how you found your purpose?

This is certainly not the most fun tale to tell, but here goes. I always knew I wanted to help people on a large scale way. This was baked into me by my parents. My mom was brilliant, who suddenly left the library while pursuing a degree at Harvard, because she realized she wasn’t helping anyone by studying books. She went on to dedicate her life to major issues like improving access to housing and education and ultimately got her PhD so she could teach at our local state university’s commuter campus. My dad was more of a wiley opportunist, tackling big issues when he saw the chance. He was in politics working on race relations and poverty and, because of a little white lie, ended up advising Jimmy Carter to help improve rural healthcare.

So I knew I wanted to do something similar and I loved research, and believed that a PhD in sociology would give me the tools. Unfortunately, it was through loss that my parents ultimately narrowed my focus.

My honeymoon was in December 2015. We flew halfway around the world to a tropical island to relax, something I never do, and was shamefully unsuccessful at since I spent two days rewriting my first journal article submission. I did relinquish my phone, however, and shortly before flying home, I turned it on and was surprised to find no notes from my mother. That surprise turned to fear when I could not reach her. My mother and I were the type to speak every day, who I shared everything with. At my wedding in her backyard, I had to redirect myself as I ran to her to share moments after speeches and toasts instead of my groom.

As soon as our plane touched down in the U.S., I found a note from her that she had just been released from the hospital for a second bowel blockage in two weeks. Emblematic of what I would soon learn firsthand about urban-rural cancer care disparities in the U.S., she had been transferred by ambulance twice to MGH 3.5 hours away because there were no available beds near her home in rural Maine. I was flying home to Boston where I was completing my PhD in sociology at Harvard so one of her friends flew up from DC to stay with her at a hotel in Boston until I returned. By the time I landed in Boston, she was back at MGH for a third bowel blockage.

The subsequent operation revealed what the doctors expected, but I had thought unfathomable. My all-organic, kayaking mother had a large metastatic tumor, which would later be diagnosed as stage IV colon cancer with a prognosis of 3-5 years. I awoke at 5 the next morning to make sure that I broke the news to her and not her doctors at rounds. When she awoke, I tried to gently share the surgery results with her. In that moment, it felt the world slightly tilted as I took my first steps to care for my mother: “They think it’s cancer.” My mother, ever devoted to me, simply responded, “I’m so sorry, honey.” And so began our confusing, uncertain, and often painful attempts to remain mother and daughter while also serving as patient and caregiver.

The following two and a half years, despite many cherished moments and periods of calm, were devastating. My mother and I carted between her cancer center in central Maine and Dana-Farber. Maintenance chemotherapy and her fear of a bowel blockage prevented the travels she had planned for her recent retirement as cancer became her fulltime job. I struggled to balance writing my dissertation, job applications, and IVF treatments. My husband and I had planned to have a baby as soon as we married, but my mother’s prognosis added to that desire; I wanted her and the baby to have as much time together as possible, so our infertility diagnosis added pressure. My relationship with my mother also suffered. Our daily phone calls became interrogations about symptoms and chiding about nutrition. I struggled to balance being her daughter and her caregiver.

I also struggled to find a job. Because of my mother’s diagnosis and as her primary caregiver, I wanted to stay in the northeast, but I did not want to compromise on the institution’s quality since I thought that prestige would help me make more of a difference. Interviews at Yale, Brandeis, and RAND were near misses. A chance encounter led to an offer of a postdoc in Maine. I leapt at the idea of being so close to my mother; my child was only weeks old. Less than six months later, a month before I started my postdoc, my mother died of cancer.

While caring for my mother, I noted similarities between our experiences and my doctoral work. As one of the first to collect and analyze audio-recordings of HPV vaccine communication during pediatric visits, I informed interventions that improved vaccination rates, published several first-authored papers in high-impact journals, and planned to develop interventions to raise HPV vaccine uptake. As my mother’s caregiver, I learned that the struggles of cancer that I hoped to prevent via HPV vaccination were unimaginably worse than I had thought. I also saw parallels between my vaccine research and what my mother and I experienced – medical uncertainties, time-scarce providers, families and oncologists who struggled to communicate uncertain and upsetting realities, and families unsure of what questions to ask and to whom. My postdoctoral training at Maine Medical Center with a palliative care doctor contextualized my experiences. There, I joined studies of prognostic communication among cancer patients. I also received a crash course on the difficulties that rural cancer patients, their families, and providers face. My mother and I encountered similar issues, but at Maine Medical Center, I met caregivers who juggled work, childcare, and driving eight hours to see a specialist, only to make the same drive the next day for treatment.

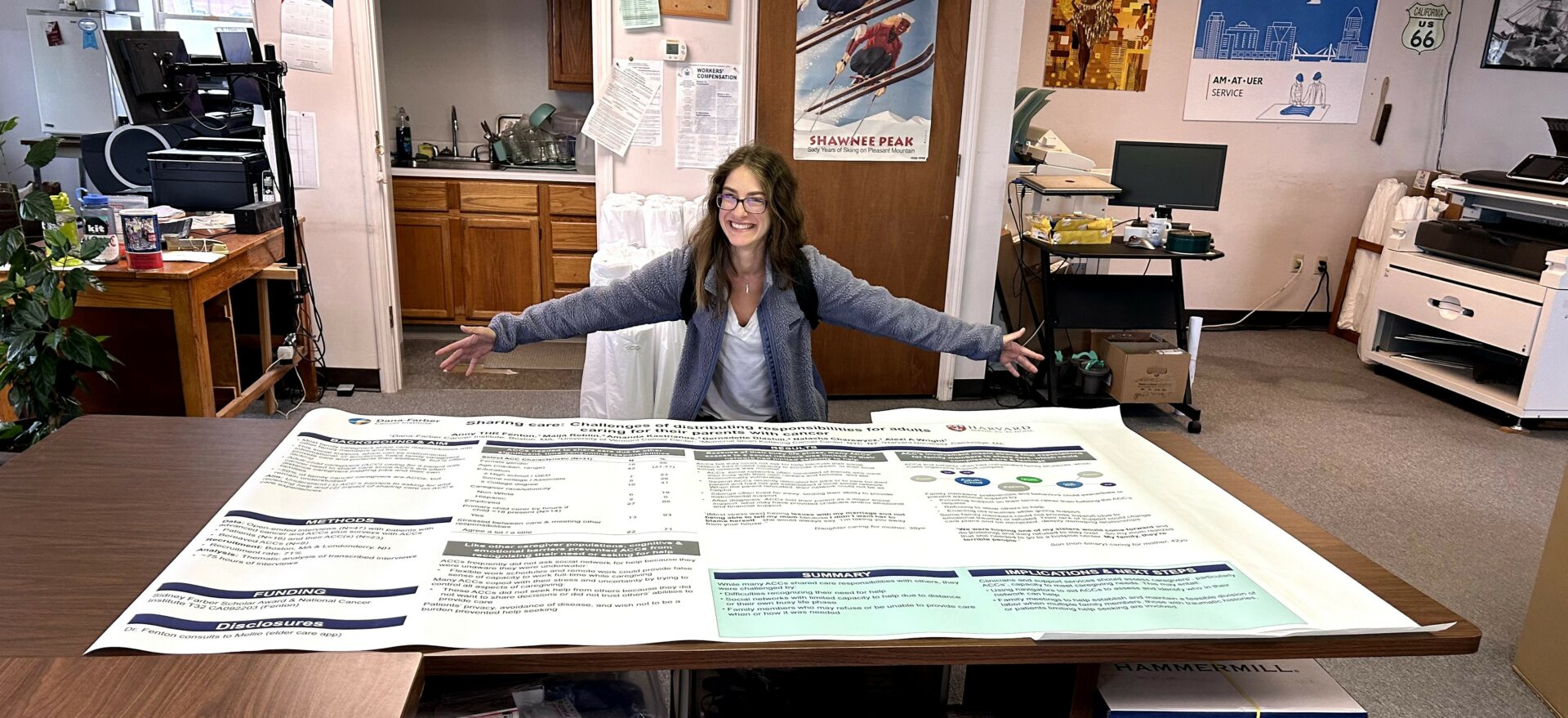

Ultimately, I decided to leave an established research program on vaccine hesitancy (DURING A PANDEMIC) because I felt so strongly about helping caregivers and patients facing cancer. I reconnected with Dr. Alexi Wright, my now mentor, with whom I had a budding collaboration when my mother’s needs grew. Dr. Wright asked me to join a study of ovarian cancer patients’ fatigue experiences on a novel therapeutic agent. During this time, she urged me to apply to Dana-Farber’s TOPS fellowship to pursue caregiving research. With this fellowship, I realized little was known about my and my mother’s experiences navigating cancer as child and parent, especially those in rural areas. With Dr. Wright’s mentorship and network of collaborators, several of whom now advise me, I launched several caregiving studies to describe the challenges that adult-child caregivers face, how they compare to the well-studied spousal caregiver, and what factors affect adult-children’s caregiving burden.

Let’s take a small detour – maybe you can share a bit about yourself before we dive back into some of the other questions we had for you?

As a medical sociologist, I use qualitative and quantitative methods (e.g., interviews and statistics) to study the vital role and experiences of cancer caregivers (those caring for a family member or friend) and their impact on patients and their care. I focus on adult-children caring for a parent with cancer, a vastly understudied population that accounts for half of cancer caregivers in the United States. Often called the sandwich generation, adult-child caregivers frequently juggle caring for their parents and their own children with full-time jobs. My long-term goals are to (1) understand how to help these families cope with and navigate the distress and challenges of an advance cancer diagnosis; (2) prove that supporting caregivers is good for healthcare institutions’ and employers’ bottom line, and (3) use my findings to build innovative, evidence-based, scalable programs to improve families’ lives.

So, in short, I’m an academic. Officially, I am an Instructor of Medicine in the Division of Population Sciences at Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School’s Department of Medical Oncology.

I also occasionally advise and consult for for-profit and non-profit companies that are trying to understand how to better support caregivers whether it’s helping them measure their impact or develop new programs in order to figure out what they should actually focus their efforts on. I would love to do more of this since I think these institutions and programs have the best chance of supporting caregivers.

If you had to pick three qualities that are most important to develop, which three would you say matter most?

Doing what’s important and/or personally meaningful. I’ve spent a lot of time doing things for work and socially that I felt like I should do instead of doing what would move me towards my larger goal (i.e. making people’s lives better) and/or be personally important and meaningful (spending time with friends instead of clearing my inbox). This does not mean skipping every bullshit task…if completing the bullshit tasks keeps you employed, that’s probably working towards your larger goal.

Relatedly…saying no to new projects (both personal and professional). We only have so many hours in a day, so, if there’s any reason to say no to a project, you should probably say no.

Do you want to be right or do you want to win? My father always said this to me when I was tempted to burn things down out of principle. Ultimately, we have to navigate a system that is often unfair, and so, if we want to reach a goal, we might need to bite our tongue and instead strategize…and secretly hoard a bunch of voodoo dolls at home to secretly exorcize our angst.

Thanks so much for sharing all these insights with us today. Before we go, is there a book that’s played in important role in your development?

This is hokey, but I have forever adored Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney. It takes place in Maine and is the story about a girl growing up who wants to travel and eventually move home to live by the sea. That is all very good, said her grandfather, but how will you make the world a better place? Yah, nothing to do with my life narrative. Heh. Heh. I get this book for every friend when they have a baby (and some temporary tattoos…for the baby of course).

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.dana-farber.org/find-a-doctor/anny-fenton

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/anny-fenton-7b53848/

- Twitter: @anny_fenton

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.