Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Chavisa Woods. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Chavisa, so great to be with you and I think a lot of folks are going to benefit from hearing your story and lessons and wisdom. Imposter Syndrome is something that we know how words to describe, but it’s something that has held people back forever and so we’re really interested to hear about your story and how you overcame imposter syndrome.

It’s not a syndrome. I AM an imposter. Most current social systems don’t align with my values. Artists are best as disruptors and spies. Don’t let them assimilate you.

If you feel you don’t belong, that’s probably a good thing. If you feel like you’ve slathered on a fake corporate sheen to make a living, just keep it up. It’s all fake anyway.

And if some ego pirate talks down like you don’t know how to hustle, remember: these are the same folks who say things like, “time is money.” But time isn’t money. Although our experience of it is immutable, time bends with gravity, flows differently relative to the location of the observer. Our economy, by contrast, is built with no regard for the laws of physics, let alone the existential ticks that unwind in the hearts of humans.

Great, so let’s take a few minutes and cover your story. What should folks know about you and what you do?

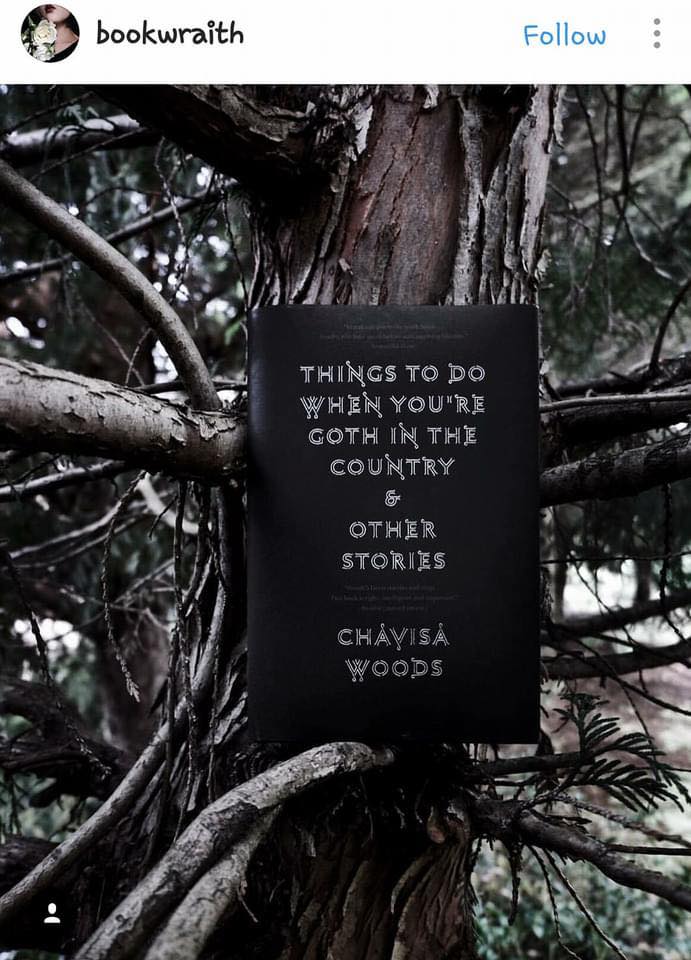

My last book of fiction, Things to do When You’re Goth in the Country, was called “a leftist Hillbilly Elegy.” It came out in 2017, and it got a lot of press for being about Trump country. But I wrote it before Trump was even really running for president. I grew up in rural, poor, conservative, religious America. I moved to NYC when I was twenty-one years old, and cities like New York are these great liberal bubbles, which is good if you live there. I mean, no matter what Fox News tries to tell you, the quality of life is just so far beyond what you find in conservative areas. But I think it’s easy for liberals and leftists to get comfortable and forget that anyone outside of their bubbles could ever be relevant to their lives.

I think, with my writing, for years, I’d been trying to sound the alarm; to say that we have a serious problem in this country. We need to pay attention to these people. I was trying to tell people, there’s a very unique sickness growing; a rotten spot on the heartland that is not healing. And I worry that a lot of people thought I was writing about something really niche at the time, something novel and interesting, but so far removed from their lives… and now this sickness has infected everything.

So, I’m not sure what to do anymore. I keep writing. I always keep writing. I’m working on some things that are much clearer now; nonfiction. I’m working on some essays that say what I mean much more clearly and directly than I was able to while working with the magical realism and the short story collection. I’m going to see how that goes.

Looking back, what do you think were the three qualities, skills, or areas of knowledge that were most impactful in your journey? What advice do you have for folks who are early in their journey in terms of how they can best develop or improve on these?

One. Look directly

Two. Describe every aspect of what you see

Three: Especially if it’s something you’re not supposed to look at or talk about.

What I mean by this is, I always had a tendency to look directly at things and describe what I saw, especially at the things I knew I was supposed to pretend not to see. This is the job of a writer. And it upsets people. Your job is to upset people.

Like, for instance, in the county where I grew up, there was an active Klan. In fact, the Grand Dragon of the local chapter lived in my town. And when I was a teenager and would complain about the Klan, and like, suggest we try to oust the Klan or protest them or anything, people would push back, with like, “Yeah, but they don’t really DO anything. Why don’t you just ignore them?” They acted like I was the drama for being upset about the presence of the KKK.

When I was a kid, I internalized this, and felt guilty and embarrassed, and thought maybe they were right; maybe I was just being dramatic whiny teenage girl for being so upset. It made me feel crazy. I had to think, like, what did the Klan actually DO? They weren’t exactly publicly active. From what I knew, they held bonfire potlucks in the fields off the backroads throughout the fall. They rode their horses around these bonfire parties and drank beer and ate Miracle-Whip-based noodle salad and talked about white pride. They had private meetings in private homes, and they gave membership cards out to teenagers. Throughout the year, a couple of boys would show up to school occasionally and show off their Klan cards like it was a joke, and then, sometimes, more seriously.

I guess if you were white, and straight, and fairly normal, they really didn’t do anything to you. But I was not straight or even fairly normal, and my senior year, a boy who had showed me his Klan card, not jokingly, started threatening to kill me because I was openly gay and the girl I was dating (in Saint Louis) was black. And the year before, his older brother had killed himself and his own child. And I knew he was capable of serious violence, and because he had previously told me he was affiliated with the Klan, whether it was true or just something he said for shock value, I was never sure if it was just him targeting me, or a larger group, as well. And I was genuinely afraid for my life showing up to high school some days. And I didn’t feel safe in my hometown. I felt hated. And I moved away as soon as I finished high school, like within eight weeks. And I still have nightmares about my hometown. And there were things I loved about where I grew up, that I loved so dearly and just had to walk away from forever.

And I understand now how the presence of something like that works. I understand why my town, which was historically a sundown town, was still 99% white the year I graduated, in the year 2000, even though its official sundown ordinances were gone by the 1970’s. I understand how the presence of fascist organizations like the Klan work quietly in the shadows, isolating certain individuals and groups, and pushing people out, and keeping them out, decade after decade. And somehow, they do it in a way that allows the larger populace to say, “They’re not really doing anything. Just ignore them.” And for some reason, writing about this, even now, twenty-five years later, I still feel… ashamed and silly… for making a big deal of it. I still feel like maybe I’m just a dramatic teen girl making a big deal of nothing. They implanted that idea in me, and it’s hard to out. It’s like some microchip, I need to gouge out of my flesh, but no matter how much I jab at myself, and can never quite locate the illusive little bug.

But it doesn’t matter if I still feel that way. To be a good writer, you just have to push through all that, stop hacking at yourself and simply describe what you see, especially if people are telling you not to look at it.

How would you spend the next decade if you somehow knew that it was your last?

If I had ten years left, I’d definitely get out in the ocean more, make love more, finally read Moby Dick… Maybe it’s really just the ocean that’s calling me… I’m seeing as I say this. Maybe I should just get on a boat with a lover, take to the sea, and bring Herman Melville along for the ride.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://chavisawoods.com/

- Instagram: chavisawoods

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/chavisawoods

Image Credits

Photo with burning flag by Liz Liguori

Photos of Steve Cannon and Chavisa Woods by Nikki Johnson

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.