We were lucky to catch up with Heidi Dellafera eagleton recently and have shared our conversation below.

Heidi , sincerely appreciate your selflessness in agreeing to discuss your mental health journey and how you overcame and persisted despite the challenges. Please share with our readers how you overcame. For readers, please note this is not medical advice, we are not doctors, you should always consult professionals for advice and that this is merely one person sharing their story and experience.

That I’m writing this now is astonishing having lived with undiagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for the better part of my lifetime. In grammar school, I could have been the poster child for ADHD had it been thought of as an “affliction” for young girls as well as young boys. But it wasn’t, and it would be years later before girls, let alone a woman in her sixties, would be diagnosed. And it would take years before that woman finally would believe that she wasn’t “stupid” or “less than.” And that woman would be me.

Before my diagnosis with ADHD, I fought self-doubt. The seeds had been planted by my high school guidance counselors who said based on my entrance exam scores (SATs), that college was out of my reach and capability. My dad, my biggest fan, would have none of it. He told me to dig deep inside myself, to avoid doubters, and by tweaking a famous quote by Theodore Roosevelt, to “reach for the stars but to keep one toe on the ground.” He said that if I worked hard and kept my head on straight, I could be whatever I wanted to be regardless of what others thought, even those “in the know,” or those who laughed at my ambition, which at the time was to become a trial lawyer. Everyone needs a “biggest fan” like that.

I shined academically except in math, my nemesis. Yet despite my good grades, I struggled with standardized tests. I never met one I liked or had success with any that I had taken, whether it was an SAT, LSAT (law school entrance exam), or a state law or architectural licensing exam. I knew a lot, it just wasn’t evident in my test scores no matter how hard I tried or how hard I prepared for the tests.

But, somehow in spite of it all, along the way, I learned to refuse to take “no” for an answer. It was a skill that would serve me well. If the front door was closed, I went through the back door, side door, or basement door. And often the front door was locked as well as closed.

Proving my guidance counselors wrong, I graduated with an Associate of Arts degree (A.A.) in 1968 from my “safety school,” a junior college, which at the time was considered one step above a “finishing school.” It was a detour I had to take due to my lousy SAT scores. Later in 1970, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree (B.A.) with departmental honors in government from the all-women’s four year college I had wanted to go to straight out of high school.

Law school was next. Not surprisingly, my LSAT scores were dismal, 326 out of a possible 800. Suspecting that my scores might be a problem, I visited the law school I wanted to attend to ask that they be waived and that I be accepted based on my academic record and a glowing recommendation from the head of my college government department. Before the admissions committee, I argued that I was a great student, just a horrific standarized test taker with a history of standardized test failures to prove it. I won my first case.

Three years later in 1973, I graduated with a law degree (J.D.), one of about seventy-five women out of a class of around seven hundred and fifty students, and by mid-1974, I was on my way to fulfilling my high school dream of a career in trial law. That same year I passed the bar exam after being tutored on the “art of taking standardized tests,” which I learned had more to do with methodology than with actual knowledge and nothing to do with being a good trial lawyer.

Once that was behind me, I hit the ground running. My my anxiety about being “stupid” and “less than” drove me to work harder and longer than most of my collegues and far more than what was necessary. I slept less than what I needed. I became a classic overachiever, juggling multiple balls in the air with abandon. Few could keep up with me, my energy, or my hyper-focusing. Few wanted to. Moderation wasn’t a part of my vocabulary.

But then just a few years into my legal career, the unexpected happened. Life got in the way as it always does. After I married in 1976 and shortly after my dad’s death in 1977, I became pregnant. That wasn’t part of the plan so early in my marriage or my career. It wasn’t even on my radar in high school, nor was the loss of my dad, my “anchor” and “my sounding board.”

I liked practicing law and I was on partnership track at my law firm. But the firm’s billable hour expectations with a new baby seemed beyond my reach. Combined with my lack of confidence, and the fact that there was little support for working career mothers back then, I decided that I needed a course change, so reluctantly I left the law in 1978. I couldn’t cut it, I thought. I wanted a career though, and if it wasn’t law, it had to be something else. I still had to prove myself especially to all those who had doubted me.

That something else would be architecture, an interest I had developed doing construction contract law for the firm I was leaving and while renovating the 1850s farmhouse my husband and I had bought shortly before we married. Naively, I thought architecture would be more compatible than trial law with my family life. I was wrong. Architecture was just a different kind of pressure, with more years of schooling and a husband and by then two children.

I struggled to keep up. Like law, architecture required an enormous commitment and so did my family. I spent many “all-nighers” in the design studio, going back to campus after tucking my children into bed at night, to crank out designs and building models. I had never pulled an “all nighter” in law school. During the day on campus, I was known as that “older student” with two kids in tow. It was clear to them from the outset that my children and I were a package deal, an anomaly for college students in the mid-1980s. My youngest son came to school with me. I set up his playpen under my drafting table. My older son wasn’t far off. I could see and hear him on the playground at a small private school across the street from the architecture school building. After a few fits and starts, with time outs here and there, I finally received my Master of Architecture degree (MArch) in 1986.

Sometimes, in my more somber less frantic moments, I questioned what I was doing. In my heart I had accepted that I was different, and more importantly that I thought differently. My life to date had left no doubt about that. But what I had accepted in my heart then didn’t matter. I still had to appear to “fit in” and appear on the outside, the side everyone would see, in this case, to be an architect’s archtect.

After getting my MArch, I spent the better part of ten years first in Missouri and then after relocating to Texas trying to pass all six sections of the architectural licensing exam to be able to call myself an “architect,” hang up my shingle, and start my own practice. Eventually, and once my three-year internship under a practicing architect was finished, a requirement to sit for the exam, and having to start the exam all over because of a move to a different state, I passed all six sections. But I hadn’t passed them in the right sequence and all sections at once for credit and a license. The end result was that I could not nor could ever be able to call myself an “architect.”

My self-esteem took a big hit. The scars had grown deeper. My “stupid” and “less than” meter was off the charts. I felt like a total failure. Depressed, I decided to get help with a cognitive behavioral therapist in Houston where we were living at the time.

After many therapy sessions in my sixties, many tears, and an ADHD diagnosis, I became convinced that the time I spent chasing the architectural licensing exam was time not well spent. Eventually, I understood that the chase had been driven entirely by my relentless anxiety, like so much of my life before had been driven, believing that I was “stupid” and “less than” and my unstoppable need to prove that it wasn’t so.

I’m grateful that I didn’t have to pay the ultimate price, estrangement from that which brings me my greatest joy, my family. During the years I was on the chase I came close to almost losing the very thing I had wanted most, a healthy balance between my career and my family life, a balance which women today still struggle to achieve. By the time I appreciated this, my two sons had grown up, graduated college, and become awesome young men with families of their own.

During those same years though, my career suffered little, it flourished. In 1989, I started my own architectural firm, Royse Eagleton Architects, partnering with an architecture school professor, a licened architect. In 2004, I folded our architectural firm into a combined practice called Open Design & Development, Inc (The Odd Group; a development, architecture, construction, and real estate company, and for over fifteen years I was its principal and owner. During this time from 2008 to 2011, I also was an Adjunct Professor of Architecture at a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) in Prairie View, Texas and a guest lecturer at several college and universities with SAT, LSAT, and GRE standards so high that, ironically, I wouldn’t have had a prayer of being accepted to a first-year class there when I graduated from high school in 1966. Today, I am a writer, my company is Spintails, LLC. Not bad for a “girl” who wasn’t college material.

In retrospect I believe that I navigated my life’s journey and the bumps along the way because I unwittingly embraced the positives of my ADHD by using my differences and my ability to “think outside the box” to carry on despite my high school guidance counselors’ “dire predictions.” Going to a junior college, my law school admissions visit, hiring a tutor to teach me the “art of taking standardized tests,” partnering with a licensed architect, and taking my kids to architecture school with me are evidence of all of that. However, at the same time, I also believe that in retrospect my ADHD challenges: “impulsivity, perfectionism, and my inability to moderate,” often in overdrive and unchecked, resulted in me staying in the I have to prove that I’m not “stupid” or” less than” game way too long.

My ADHD and I will always be a work in progress. I can only speak of my personal experiences living and aging with ADHD both diagnosed and undiagnosed, I’m not a mental health professional. I can say that passion, a sense of humor, and the courage to change course in the face of fear and do it anyway helps. Flexibilty doesn’t hurt either. I still do a million things, not just all at once. After all, I am who I am.

Today I look at my ADHD not as a “disorder” or “deficit” or negatively, but as a “difference,” an attention and/or hyperactivity difference with positives to be harnassed, and challenges to be addressed. Going forward as I age with ADHD, my job is to embrace and announce its positives: “creativity, tenacity, boundless energy, curiousity, the ability to hyper-focus, and to think outside the box,” and to negotiate its challenges: “inattention, difficulty concentrating, poor listening skills and impulsivity.” Not an easy task at any age, but a necessary one. And above all, my job is to hold close to me the differences that make me, me, to find joy, and to live life to its fullest from the front seat focusing on what’s working and drawing from it.

Thanks for sharing that. So, before we get any further into our conversation, can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what you’re working on?

Today, I am a writer, my company is SpinTails, LLC, and I am chosing to answer this question focused only on my writing career, although my previous careers as a lawyer and running my own development, architecture and construction company are a large part of my life’s story. Both provided a strong foundation for who I am and what I do today and I’m grateful to have had those career opportunites.

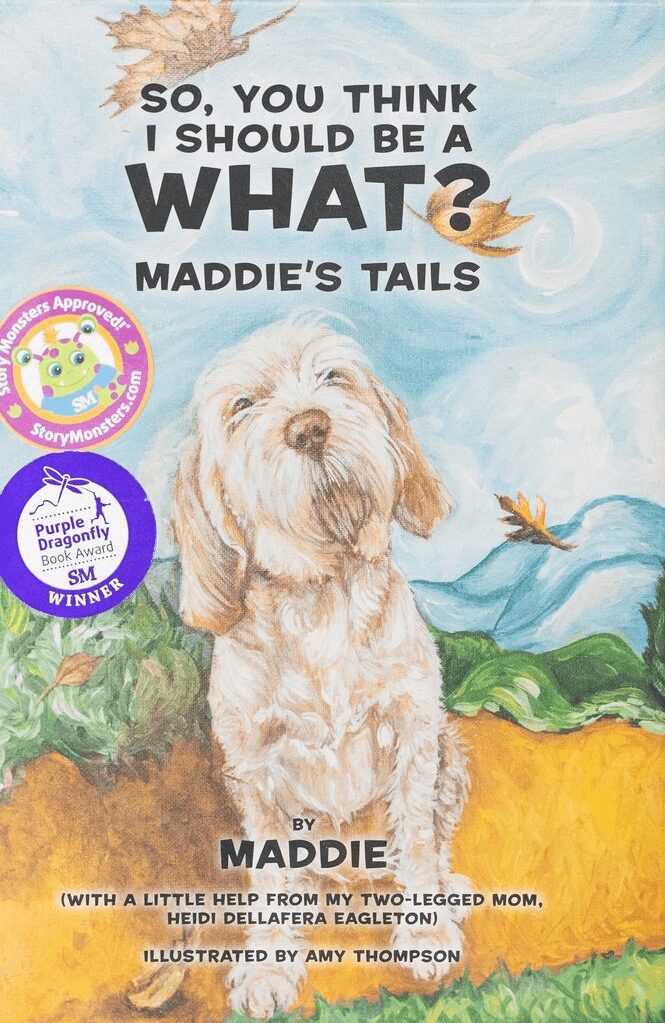

Since 2020, I have written and published two children’s chapter books of a five part series, “Maddie’s Tails,” a biography of my dog’s life, Maddie, an Italian Spinone, loosely drawn on my experiences growing up as a girl with undiagnosed ADHD. The first,”So You Think I Should Be a What” was published in 2021 and the second, “Road Trip with Tia.” was published in 2023. Both are in my dog’s words and from her point of view. “So You Think I Should Be a What” was showcased by “Readers Magnet” at the 2024 LA Times Festival of Books, April 20th-21st at University of Southern California and won a “Story Monsters Approved Award” and a “Purple Dragonfly Book Award.”

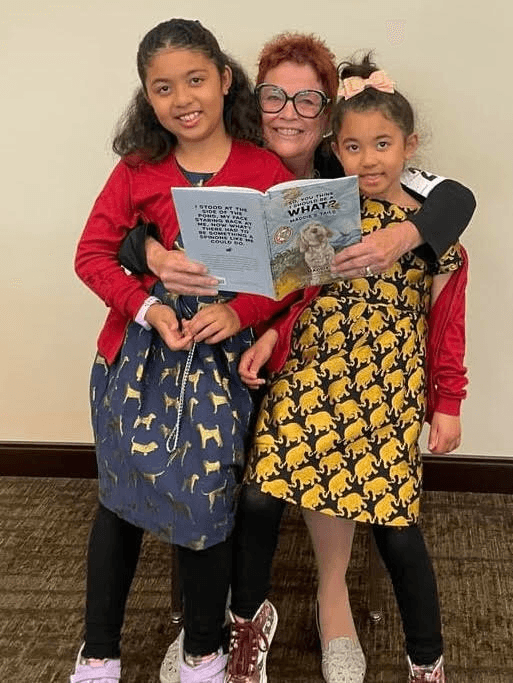

In conjunction with writing children’s books, Maddie and I also work directly with children as a way of giving back. We recently visited Lincoln Fundamental Elementary School in Corona, California to read “So You Think I Should Be a What?” to sixty second graders on Read Across America Day. Maddie is an Animal Samaritan Therapy Dog in Palm Springs, California where we live during winter months, and participates in the “Read to Dogs” library program throughout the Coachella Valley. We are looking forward to continuing our therapy dog work by participating in the “Reading with Rover Program” in Redmond, Washington now that we are back in Seattle where we live during summer months, The third book in the “Maddie’s Tails” series will be based on her experiences as a therapy dog reading with children.

My short story about living on a floating home, “Mi Sueno” can be found in “Landless in Seattle published in 2023,” an anthology of work from artists, authors, photographers and architects who live on floating homes on Lake Union and Portage Bay in Seattle.

My blogs can be found in “Letterlife.se” a digital platform for girls and women with ADHD and on my website, https://www.heidieagleton.com. I currently am writing a book about my personal experiences “Aging with ADHD.” I will be participating in a Peer Support Group discussion at the 2024 Annual International Conference on ADHD in Anaheim, California, November 14-16 to encourage the community to learn more about aging with ADHD and ultimately help those older adults with ADHD thrive from developing research and alternative therapeutic possibilities out there on the horizon.

There is so much advice out there about all the different skills and qualities folks need to develop in order to succeed in today’s highly competitive environment and often it can feel overwhelming. So, if we had to break it down to just the three that matter most, which three skills or qualities would you focus on?

The three qualities that were most impactful on my journey were my ability to:

I. think “outside of the box,” appreciate differences, including my own, and never taking “no” for an answer;

2. have passion, a sense of humor, and the courage to change course in the face of fear and do it anyway; and,

3. ultimately believe in myself, learn from my mistakes, and hug myself every day.

My father’s advice, not mine, says it best for those of you who are early in your journey……. “dig deep inside yourself, avoid doubters, and ‘reach for the stars but keep one toe on the ground.'” I carry his thoughts in my heart wherever I go to this day. I encourage you to do so too.

All the wisdom you’ve shared today is sincerely appreciated. Before we go, can you tell us about the main challenge you are currently facing?

My biggest challenge as an older adult living with ADHD is to combat commonly accepted and internalized ageist stereotypes, or what is thought to be evidence of cognitive decline, or the beginnings of dementia, among older adults, “inattention, difficulty concentrating, poor listening skills and impulsivity.” For many aging adults, like me, these are ADHD challenges that have been with us, diagnosed or undiagnosed for almost a lifetime, and are not necessarily a part of the “normal” aging process, as is often thought. Few ask whether these “stereotypical behaviors” are something else, like ADHD, although it has been estimated that about two million people worldwide over sixty-five live with ADHD.

While I’m not a healthcare professional, much of my writing of late addresses aging with ADHD based on my own personal experiences to get the word out there on its issues and to encourage more research and public discussion on how ADHD and its co-occurring disorders, in my case, anxiety, impact the everyday lives of aging adults. My hope is to help give older adults with diagnosed or undiagnosed ADHD a platform and an opportunity to connect with the ADHD community and to raise public awareness of diagnosed or undiagnosed ADHD among older adults.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.heidieagleton.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/heidieagleton

- Facebook: https://facebook.com/heidieagleton

- Youtube: https://youtu.be/GQ7Tn0t_F-0?si=MsKrwXqElcrzf4pc

- Other: https://www.linkedin.com/in/heidi-eagleton-a6153b11/ (mistakenly left out of the linkedin space)

Image Credits

Dipan Desai Photography

https://dipandesai.com

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.