We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Janelle Christa a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Janelle , thanks so much for taking the time to share your insights and lessons with us today. We’re particularly interested in hearing about how you became such a resilient person. Where do you get your resilience from?

Picture this: you are nowhere. No body, no time, no language—just a black, endless void and the sensation that you’ve been dropped into the worst corner of hell. The only image in your mind is a worm eating itself over and over, forever. And you are the worm. There are no people, no souls, no God, no exit. In reality, you’ve overdosed on ketamine and your body is slowly dying somewhere, but where you actually are feels worse than dead. It’s annihilation with a pulse. Crawling back from that kind of nowhere—that’s where dissociation began to mutate into resilience, where the part of me that had always floated above the wreckage finally decided to climb out of it instead.

For me, resilience comes from learning to breathe inside the blast radius and call it home. It did not arrive as a gift; it was carved out of years spent wrestling my own nervous system for the right to stay alive. For about thirty years, suicide wasn’t an abstract concept; it was background radiation, humming in my skull from the moment I woke up until I finally passed out. Every day was a negotiation between a brain that wanted an exit and a self that refused to hand over the keys. The “strength” people like to compliment was, in reality, thousands of tiny, grimy acts of defiance: brushing teeth when it felt pointless, answering texts when disappearing sounded holy, walking into hospitals when shame said stay home and bleed quietly.

During all of this, I was still showing up on sets—memorizing lines with a brain that wanted an off‑switch, hitting my marks while part of me was calculating exits, pretending to be other people when I was barely holding on to myself. The camera kept rolling, and somewhere in that tension between survival and performance, the seeds of the director I would become were already being planted.

Bipolar disorder taught me early that my own mind could be both the weapon and the battlefield. Resilience, for me, is not about being unbreakable; it is about learning how to walk while shattered, to override the screaming impulse toward self‑destruction so many times that it starts to become a reflex in the other direction. It is the muscle memory of not giving in. My “personal growth” didn’t happen in yoga studios and retreats; it happened under fluorescent lights, in psych wards and detox rooms, wrapped in hospital gowns that never quite closed in the back. Mental health crises, substance use, spinal fluid leaks, a hysterectomy, a traumatic brain injury—my body has been a recurring crime scene. Every time, the script could have ended there; every time, it didn’t.

Resilience grew in those ugly rooms: learning how to advocate for myself when I could barely string a sentence together, how to sign consent forms with shaking hands, how to keep choosing treatment even when part of me was addicted to chaos or numbness. It came from realizing that if my body kept insisting on survival through all that, maybe there was something in me worth protecting, even when I couldn’t feel it. I was born into instability: a very young mom, welfare, adoption by her husband, then the revolving door of relationships and family structures. By eighteen, I had fourteen siblings and a crash course in emotional whiplash. There was trauma threaded through it all—things that don’t need detail here to be real—but the net effect was simple: the ground was never solid, so I had to learn to walk like it was shaking.

That childhood taught me to read a room in seconds, to anticipate explosions, to find the quietest corner in a house that didn’t have any. It taught me to mother myself long before I became a mother to anyone else. That is where my resilience first formed: in the gap between what I needed and what was available, in the decision to become the adult I couldn’t find. Becoming a single mom at twenty‑one welded a different kind of steel into my spine. Suddenly, survival wasn’t philosophical anymore; it had a face, a bedtime, a favorite snack. The option to disappear became something I no longer had the right to entertain in the same way. I had to learn how to parent while barely holding myself together, how to show up to school events and midnight fevers and bills while fighting my own brain for air.

Resilience, in that season, was profoundly unglamorous: it was getting up when I hadn’t slept, making decisions when my head was fogged with depression, choosing not to let my story end in a way that would become my child’s origin wound. It was dragging all my fractures into the light and saying: you don’t get to define the ending. Most people who grow up in chaos spend their lives chasing stability. I chose entertainment. I walked straight into an industry that feeds on rejection, uncertainty, and ego death, and said, “Yes, that one.” That wasn’t self‑sabotage; it was strangely logical. I already knew how to function in environments where nothing was guaranteed, where you could give everything and still lose the part, the deal, the funding, the festival slot.

The industry didn’t build my resilience; it refined it. Auditions, near‑misses, projects that fell apart at the one‑yard line—these weren’t catastrophes compared to waking up with a brain that wanted me gone. They were just another flavor of chaos. If anything, film and television became the place where my particular scars were an asset: I could sit with darkness on screen because I had lived with it off‑screen for decades. What I never could have scripted, lying in that metaphorical void or in those literal hospital beds, was the life that would grow out of staying. I went from being “just” an actress who never dared dream she could direct, to the person standing behind the monitor saying “Action,” designing sets and wardrobes, writing scripts from nothing and shepherding them all the way to the screen, surrounded by collaborators and friends.

Resilience is why I get to trade hospital gowns for glitzy dresses, to step onto festival carpets in Los Angeles, London andFrance, to sit in dark theaters on the other side of the world and watch an audience breathe with a film that started as a survival instinct. It’s why I get to live a life I never could have imagined when all I could see was the void. So where do I get my resilience from?

From learning to live inside long‑term suicidal ideation and still keep the lights on.

From psych wards and ERs and ORs where I kept signing back in for another round.

From a childhood that taught me love can be unstable and still worth seeking.

From early motherhood that turned survival into a responsibility, not a preference.

From an industry that treats “no” as punctuation, not a verdict.

More than anything, my resilience comes from my ability to inhabit chaos without letting it rewrite my ending. The life story here is only the tip of the iceberg; each chapter could be its own book. But the through line is simple: everything tried to convince me I should not be here, and every single day, in a hundred uncinematic ways, I have chosen to stay—and to make something out of the staying.

Thanks for sharing that. So, before we get any further into our conversation, can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what you’re working on?

I don’t make “content.” If you are looking for something that hits harder than the scroll—something that disturbs, awakens, and stays with you after the credits, that’s the world I live in. I’m an avant‑garde, experimental filmmaker working where trauma collides with mysticism, where mental illness stares down meaning, where horror and faith share the same frame. My work sits in the borderlands between psychosis and spiritual awakening, curse and consequence, sin and salvation; it’s built from a severe lifelong mental health condition, a body that’s been through more hospitals than holidays, and what I call my “PhD in the experience of trauma,” earned in psych wards and recovery rooms instead of ivory towers.

What excites me most is using cinema as initiation. I am not interested in noise, algorithms, or “content.” Film is a medium in the literal sense: it channels, transmits, and imprints belief. It programs us—toward conscience or toward numbness. I make what I think of as conscious entertainment: stories that drag shadow into the light and dare you, and me, to look—while never forgetting that God is still somewhere just off‑screen…

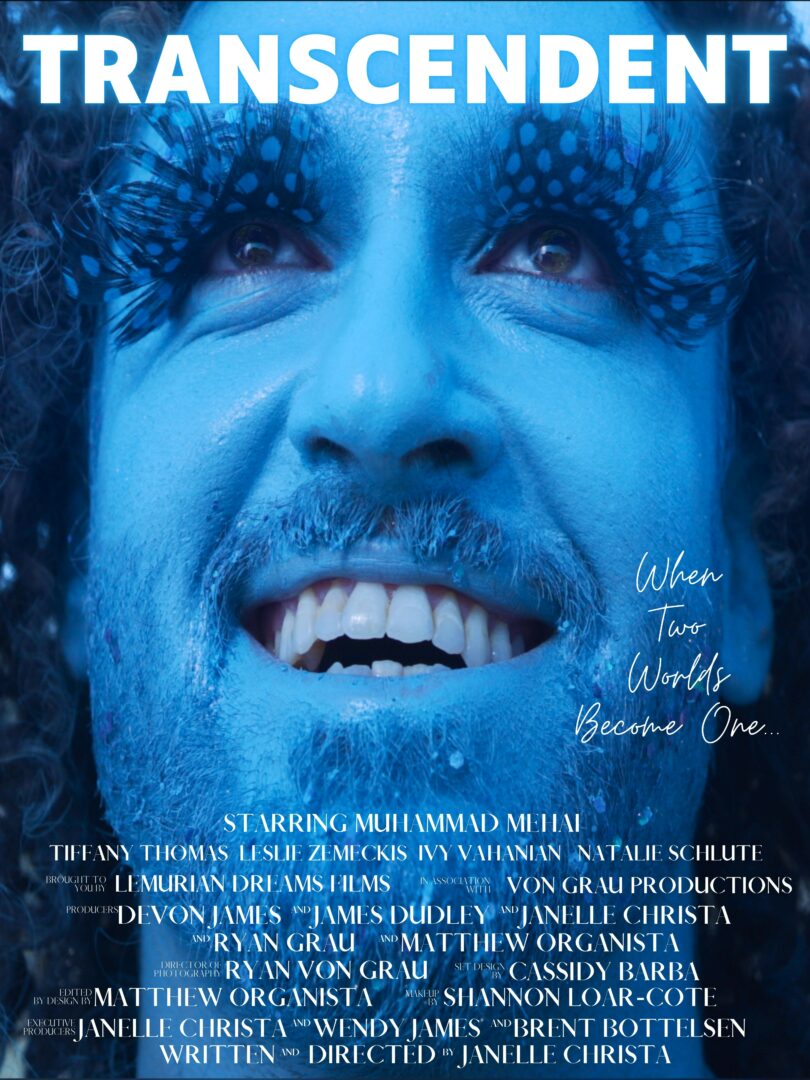

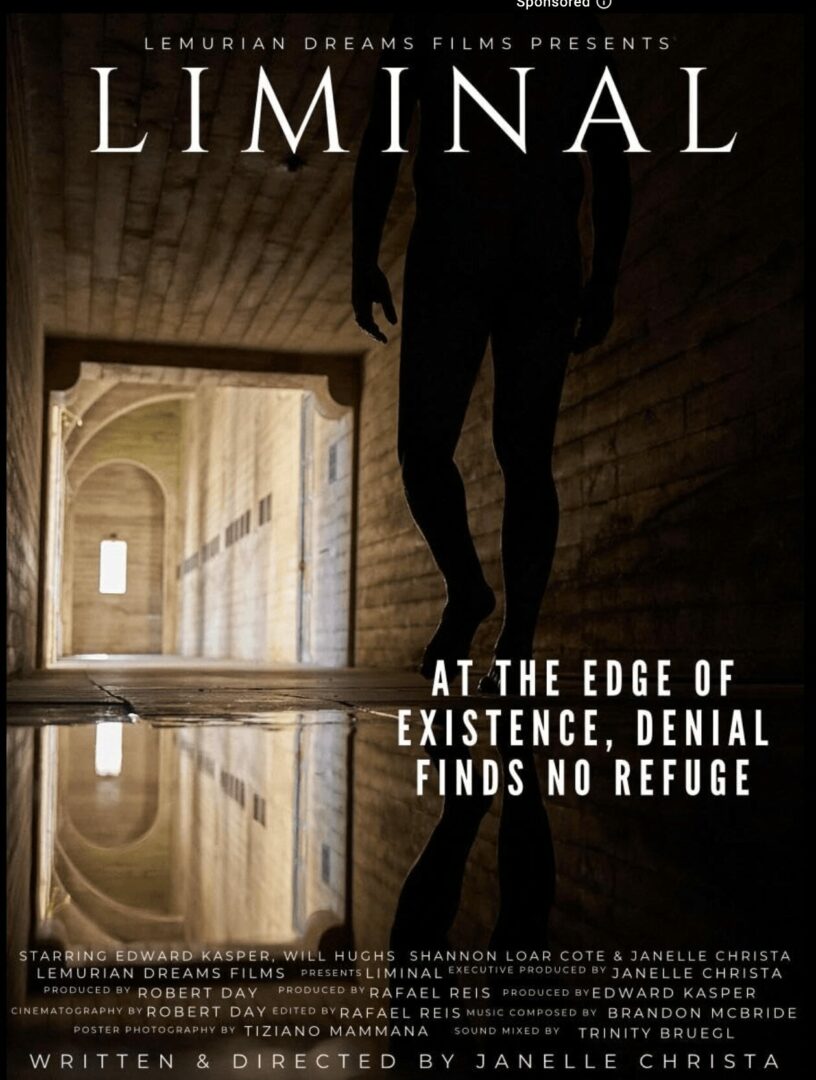

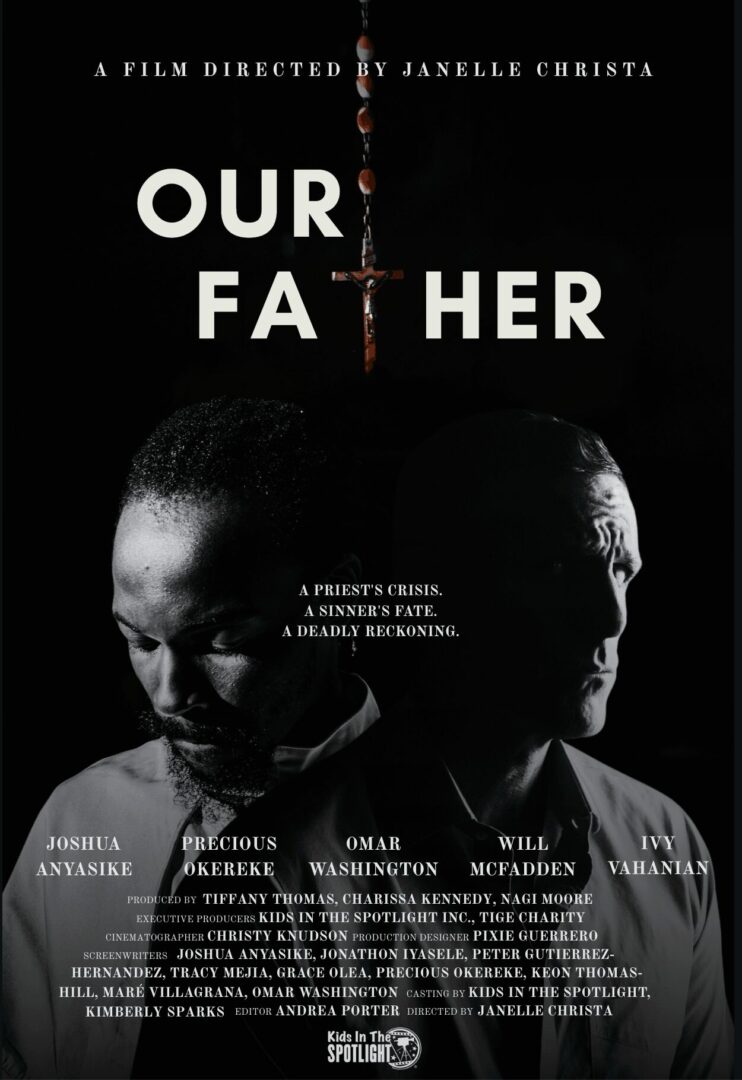

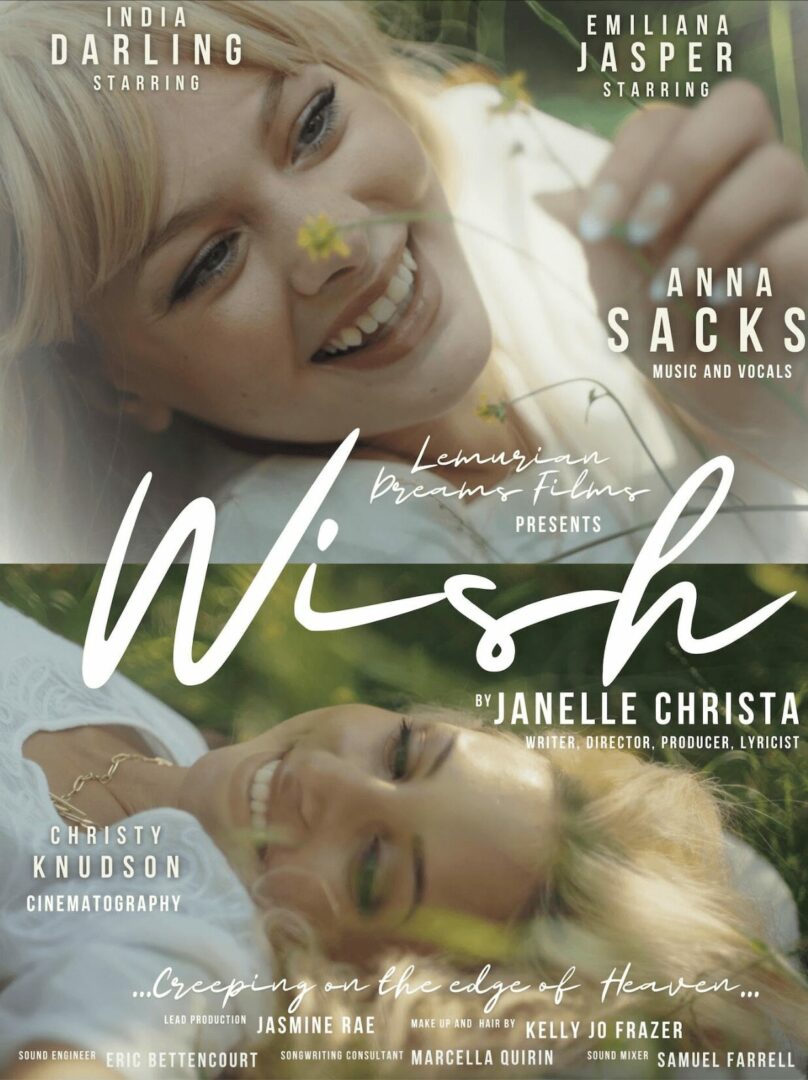

My short “Transcendent” follows an alien who drops LSD and becomes human, only to be slammed with the full weight of our contradictions—ecstasy and despair, cruelty and tenderness, love and obliteration—and has to decide if this mess is worth staying for. “Liminal” lives on the edge of a rooftop with a man flirting with suicide, forced to turn and face his own shadow instead of stepping off. “WISH” is a broken fairy tale about a young woman dying from fentanyl poisoning, grief wrapped in myth for the opioid era. “Our Father,” made in collaboration with Kids in the Spotlight, follows a priest unraveling when a parishioner confesses he is killing “sinners”—a collision of faith, corruption, and moral terror, told with youth who’ve already seen more than most adults.

A friend once called my lane “faith‑based horror,” which sounds impossible until you realize horror already demands faith: faith that you can endure what you’re seeing, that there is meaning on the far side of terror, that stepping into the dark won’t erase you. I am not interested in darkness for its own sake. I have watched work made by people who haven’t done their own inner excavation—films that feel like unprocessed pain dumped onto an audience, gritty just to be gritty. I detest that.

If I invite you into the abyss, I owe you at least a shard of light. My influences—“Fight Club,” “Natural Born Killers,” “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” “American Beauty,” “Requiem for a Dream,” “American Psycho”—are ruthless in the best way: precise, intentional, morally engaged. They interrogate identity, addiction, memory, violence, emptiness, and the rot of modern life with a scalpel, not a sledgehammer. That’s the lineage I’m in: films that unsettle you because they’re telling the truth.

Right now my primary focus is on two feature scripts I wrote at the David Lynch Graduate School of Cinematic Arts, where I had the rare and surreal experience of being in the last class to work with him before he died. That time gave me permission to trust the subconscious, to let nonlinearity and the uncanny sit right next to the sacred…

“Lucid” follows an actress in Hollywood who is abducted into a government mind‑control program—or is she? The film walks a razor edge between conspiracy thriller and psychotic break: is she being targeted by a hidden machine, or is she collapsing under untreated trauma, spiritual crisis, and industry pressure?

“Dolly” is a horror film set in Goldfield, Nevada in the 1990s, where a woman must break a curse to get free. On the surface it’s desert ghosts and haunted Americana; underneath it’s about generational trauma and the brutal work of refusing to reenact what destroyed the people before you. Both projects are in play as features, and I’m also novelizing them—“Lucid” first, then “Dolly”—to dive even deeper into the psychological and spiritual interiors of these characters.

Outside of my own slate, a huge and growing part of my work is mentoring. I’ve spent years working with youth, young adults and new filmmakers/writers/actors. I most recently began working with under‑resourced and foster youth, helping them take films from script to screen, watching them step behind a camera or deliver a line and realize, maybe for the first time, “My voice matters.”

I also offer paid mentoring and coaching for screenwriters, directors, and actors who want to go beyond surface craft into the real work: how to tell dangerous, honest stories without destroying yourself or your audience in the process. People come to me when they’re ready to stop faking it—when they want their work to have teeth, soul, and consequence, not just aesthetics.

Shameless plug: If you’re reading this and something in you is waking up—if you’re craving films that feel like rituals, entertainment that actually risks something, guidance from someone who has walked through real fire and still believes in beauty—then you’re the person I’m making this for. Everything—films, updates, mentoring details—is at www.janellechrista.com and @directedbyjanellechrista on Instagram. Those spaces are my little corner of the industry where darkness is treated with reverence, stories are invitations not distractions, and cinema is allowed to be what it has always secretly been: a kind of magic—and a doorway.

Looking back, what do you think were the three qualities, skills, or areas of knowledge that were most impactful in your journey? What advice do you have for folks who are early in their journey in terms of how they can best develop or improve on these?

My film “Transcendent” was not born out of inspiration; it was born out of a pileup. In what felt like a single, unbroken exhale, my best friend died, my sister Jolene died, my mother‑in‑law died, my dog died, I suffered a traumatic brain injury, and a month later I was hit by a car while walking. My nervous system was already wired for chaos, but this was a different level. I became chemically dependent on ketamine, spent two weeks in a mental hospital and then four months in a mental health rehabilitation center, trying to remember how to live inside a body and brain that felt hostile and unfamiliar. Out of that wreckage came a film about an alien who takes LSD, becomes human, and is slammed with the full weight of the human condition—grief, sensory overload, absurdity, fragile beauty. That alien was my stand‑in: stunned, dissociated, trying to decide if staying human was survivable, let alone worth it.

Grit, humility, and gratitude are the three qualities that carried me through that era and shaped me as a filmmaker. They are woven into every frame of “Transcendent,” even if no one watching knows it. Grit, for me, has been the repeated, stubborn decision not to disappear. It is the muscle built from decades of overriding a brain that hands me suicide as a daily suggestion and still choosing to stay. It looks like making work when it feels pointless, returning to sets and blank pages right after hospital beds and breakdowns, refusing to let pain be the author of the ending. Grit is not about being unbreakable; it is about learning to move while you are in pieces and treating that movement as a kind of prayer.

Humility has been the antidote to both ego and despair. It is admitting I do not have this figured out—that I can be cruel, selfish, jealous, wrong—and still choosing to grow instead of hiding. Humility lets me write bad drafts, take sharp notes, scrap a project, and start over without turning the whole thing into a referendum on whether I deserve to exist. It keeps me teachable in a life and an industry that never stop handing out lessons. It asks a question that cuts through the noise: are you being a good person, or just a talented one?

Gratitude is the quiet, defiant choice to notice what’s left. After bipolar episodes, addiction, medical emergencies, shattered family systems, and that concentrated stretch of death and impact, the fact that I still get to make films, tell stories, love my kids, collaborate with other humans, and breathe is not something I take for granted. Gratitude doesn’t sanitize the trauma or the anger; it just refuses to let them own the entire stage. It’s standing in the aftermath and thinking: statistically, I shouldn’t even be here, and yet somehow I am still on the call sheet. That means there is still something left for me to do. “Transcendent” going on to win somewhere around forty awards and taking me all the way to Europe for the Red Movie Awards was a strange, beautiful confirmation of that—proof that something made inside absolute darkness could carry light into other rooms.

So if there is advice in all of this for someone entering this insane, magnetic world of entertainment, it’s this: do everything you can to build a life that is the opposite of chaos. My nervous system was forged in chaos; it’s what I know. Do not make that your blueprint. In an industry this unstable, creating your own stability is not a luxury; it is survival protocol. This business is built on variables you will never control—who calls, who funds, who suddenly becomes the “it” thing and who gets ghosted. If your self‑worth and nervous system are hitched to those swings, you will burn out or break.

That is why practical stability—financial, emotional, spiritual—is non‑negotiable. Early on, a very successful actor told me that if I truly wanted a career, I had to do nothing but act: no trade, no day job, no “distractions.” Later I learned he’d grown up on a massive trust fund while he was “risking everything.” That advice, filtered through a cushion I didn’t have, was poison. It took years to understand that having a way to support myself was not a betrayal of my art but the foundation that allowed my art to be brave. When your rent is paid and you’re not terrified of the next emergency, you can take creative risks from groundedness instead of desperation.

Community is the other half of that safety net. The work itself is isolating—hours alone writing, self‑taping, editing, obsessing—and the industry adds comparison, rejection, and illusion on top. Without real people around you, it becomes dangerously easy to mistake your last credit for your worth. Community cuts through that. It is the friend who reminds you the trust‑fund guy’s path is not your path. It is the people who ask how your soul is, not just “What are you working on?” It is also built through service—mentoring, volunteering, standing alongside people whose lives are not cushioned by this industry at all. Going to Mexico to help build a home for a family, and choosing to keep doing that every year with my own family, has been part of my reset button. It pulls me out of my head and back into the reality that being alive, and being able to create at all, is a privilege.

The moral, if there has to be one, is simple: beautiful, feral, necessary things can come out of darkness—but you do not need to manufacture darkness to make great work. Let your films, your writing, your performances hold the chaos, not your life. Build as much safety around yourself as you can—through grit that keeps you here, humility that keeps you honest, gratitude that keeps you open, stability that keeps you grounded, and community that keeps you human. “Transcendent” is proof that something made in the worst season of your life can still carry you into rooms you never imagined. Your job is to survive long enough, and gently enough, to make it.

Alright so to wrap up, who deserves credit for helping you overcome challenges or build some of the essential skills you’ve needed?

In seventh grade, I got bused out of my inner-city neighborhood to a rich kids’ school on a special transfer. On paper, it sounded like a miracle: better resources, better opportunities, the kind of place adults whisper about when they say “this could change your life.” In reality, it was the year I learned how brutal it is to be the outsider in a world that runs on money and bloodlines. I was bullied relentlessly. The way I talked, the clothes I wore, the fact that I didn’t have what everyone else seemed to have—it was all fair game. By the time they eventually kicked me out, those kids had done something far more lasting than get me removed from their school: they had convinced me of who I was allowed to be. In their eyes, I was less-than, disposable, a mistake that had slipped through the front gate.

For a long time, that version of me stuck. When you’re young, you don’t realize how quickly other people’s opinions can harden into your own internal script. You start to curate your dreams to fit what you think you deserve. You choose friends, partners, collaborators who match the story you’ve absorbed: that you should be grateful for scraps, that real rooms, real chances, real belief belong to other people. The tragedy is not that those kids were cruel; kids are often cruel. The tragedy is how long I let their voices narrate my life from the inside.

Years later, my life filled up with a very different kind of person. My husband, my daughter, and my son became the center of my universe—people whose love is not contingent on performance, status, or perfection, who refuse to let me disappear into my own darkness and who, by their very existence, argue against every early lesson that said I was too much, not enough, or fundamentally wrong.

My mentor and best friend, Dick Latta, looked at my chaos and saw possibility; he treated my strangest ideas like seeds worth watering. Embrace and hug every person in your life that does this.

Tiffany Thomas (Mandalorian, The Proud Family) risked her own time and reputation to produce my first film, effectively saying, “You belong here,” long before I had the credits to prove it.

Gregory Goodman (Civil War, The Gorge, Captian Phillips) walked me through the reality of big films and still made space for my voice.

JV Hart sat down with a notebook to take notes from me, inverting the power dynamic I’d been taught to expect.

Kate Lanier took scripts from the girl who once watched Set It Off on repeat and returned them covered in notes that assumed I could handle the truth.

Somewhere in that shift—from being shaped by kids who wanted me gone to being shaped by people who wanted me to rise—I started to understand something that sounds simple but is actually radical: who you stand next to will quietly teach you who you are. The rich kids at that school taught me I was an intruder. The people in my life now teach me I am a collaborator, a peer, a creator, a soul with something to offer. The difference between those two narratives has nothing to do with destiny and everything to do with proximity.

So if there is a story here for you, it is this: pay ruthless attention to who gets a microphone inside your head. If the loudest voices around you make you feel small, replaceable, or ashamed of what you want, they are not just “friends” or “colleagues”—they are ghostwriters on your identity. You deserve people whose faith in you is steadier than your circumstances, whose success makes them more generous, not more competitive, whose honesty cuts through your excuses instead of cutting you down. Seek out those people. Learn from them. Let their belief in you raise the ceiling on what you think is possible.

And then, when you’ve gone a few miles further down your own road, become that person for someone else. That is why mentoring actors, writers, and filmmakers matters so much to me now: because I know what it feels like to be the kid in the wrong hallway, convinced she doesn’t belong, and I also know what happens when even one person takes the time to say, “You’re in the right place. Keep going.”

The moral is simple and not sentimental: the people you choose will shape the story you think you’re allowed to live…

Choose like your future depends on it—because it does.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.janellechrista.com

- Instagram: @directedbyjanellechrista

Image Credits

Tiziano Mammana – Liminal Poster + BTS

Christy Knudson – Our Father Poster

Transcendent – Ryan Grau

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.