We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Jenny Griffin a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Jenny, so great to have you with us and we want to jump right into a really important question. In recent years, it’s become so clear that we’re living through a time where so many folks are lacking self-confidence and self-esteem. So, we’d love to hear about your journey and how you developed your self-confidence and self-esteem.

When I think about confidence, I think of the quiet girl. The quiet girl liked things that were soft and liked her back. She liked words, candy stores, the weather section of the newspaper, Cinderella, sitting alone on airplanes, her haircut, face paint, salmon, errands, People Magazine, her mother, ease, being Italian, being an Aquarius, her Nana, pink, the rain, her tiny “boyfriends” who wore dresses in their finished basements when the moms went upstairs, field trips to the apple orchard, patience, Christmas pageants, Easy-Bake Ovens, her lavender bedroom, hospitals, and watching gas prices change.

When I think of the quiet girl and her early years, I remember her innocent soul, her gentle spirit whose favorite holiday was Valentine’s Day. I remember her dresses, pink and purple, free and easy.

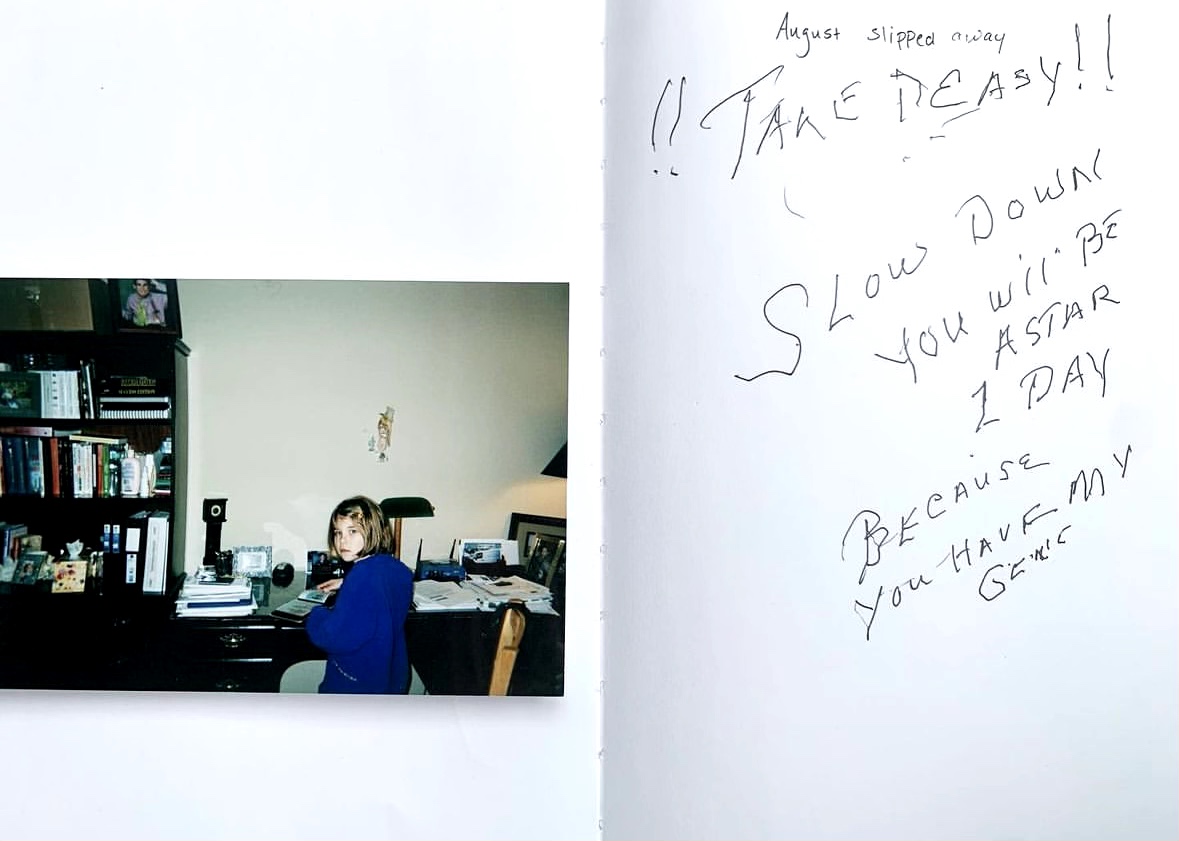

I remember how her first words were, “I do.” To many, this strange first communication was processed, filtered, and ribbon-wrapped. “She’s so smart!” they would say. “Such a big girl!” they would laugh. “It’s so cute that she thinks she can read!” they would gaslight. She could read. My Nana, who was born on Moon Street in the darkness, taught her. She would tell me her that she was special, they would sit in silence. They would lock eyes and communicate with no words until dinner was ready. They didn’t have much time, you see, as Nana and the girl met each other at the ends of a rainbow—her ready to leave, the girl ready to start—and yet, in the eleventh hour of her life, she breathed into the girl that ancient whisper from all the women who came before. Whatever it was that they wanted to do, see, or say, and whoever it was they wanted to become, leave, or love, my Nana knew that if the girl was brave enough, it was mine her’s to have. She gave the girl the gift of deep confidence. I wish Nana could have been here when everything fell apart.

The Christmas after Nana left to be with the other women, I remember a gifted jean jacket. It was perfect. I remember flashes of purple fur around the collar, red checks, and a sense of urgency. Moments like this, like when it all falls apart, require a locked bathroom door. Floating, I remember the hot tears of relief when I got to the mirror. I remember the heavy breaths, the tiny diaphragm working overtime, and my voice saying loudly, “I knew I’d look good, but I didn’t know I’d look this good.” What I felt was confidence. What I felt was self-esteem. I liked my jacket because it was soft and liked me back. I liked myself because I was soft. Inside, my soul rejoiced. “My god!” it said, “We’re alive, my god, we’re alive! Go! Go run as fast as you can toward the sun and the light and everything good; there is enough for all of us, and it has always belonged to you. You are a miracle. How happy we are to have you!”

There was silence. Then, suddenly, there was shame. “How cute!” said the other side of the door. “How dramatic!” giggled a holiday stranger. “She’s a star!” said a man’s voice. This story is not cruel or unusual. This story is not unique. I did not want to be cute or dramatic or a star. I wanted to feel alive like this forever, confident in my soft things and my words. Self-esteem is not radical; it is inherent, and it can be taken in an instant.

If it hasn’t become clear, I am a quiet girl. What I mean by quiet is not completely related to speech but to a sense of quietude—a state of stillness, calmness, and quiet in a person or place. Now, the quiet girl wasn’t always quiet; sometimes, she was very loud because she had very big feelings. When the quiet girl grew up, she decided to get very, very loud and feel nothing at all. She got so tired, and her feelings got so stuck inside that the quiet girl lost her voice for a very long time.

The shame that became my undoing crept up on me in the form of a private Christian school. It was subtle like my sixth-grade teacher wiping off stolen foundation from my mother’s bathroom in front of the class. I had my first pimple, and she said I was vain. It was confusing, like in eighth grade, when my friends and I were held after school for three hours without our parents. M*nors without representation, we were interrogated by four teachers, three eleven-year-olds, and their parents. My eighth-grade friends and I had just discovered Taylor Swift and were singing “Our Song” in the bathroom as we changed for P.E. We danced in the bathroom, we scream-laughed, we threw our shirts in the air, and we were girls together. “You are not role models,” said our teacher. “You violated my child’s innocence,” said a mother. “You should feel shame,” said my body.

I cried so hard I threw up on the rug, my back against a chalkboard. We were not monsters; we were not disgusting; we were not wrong. After this, I became very, very good to avoid feeling very, very bad. I got perfect grades. I shuddered at cigarette butts. I cleaned the house without being asked. I spent a summer looking for my tiny twin brothers, who hid in trees, cabinets, and passing cars, which made my mom very upset. If you told me I would eventually have a drinking problem, an eating disorder, and love who I’ve loved, I would tell you to kill me. You would tell me it would save my life.

Eventually, I grew up, and my parents said I would be going to the largest public school in the county. I was still the quiet girl and was not prepared for the version of me that would emerge over the next four years. I entered the building still soft, still liking things that liked me back, and I left, well, different. Self-esteem came in the form of truth or dare in a janitor’s closet on Halloween. I found that I was smart and was also good at acting. I liked the people, too; they were strange, and I was in love with them all. During the annual haunted house, someone dared me to kiss someone who made my stomach feel weird when we first locked eyes at a read-through for The Crucible. She was cast as Hawthorne, I as Mary Warren. When we kissed, it was sloppy and insane because we had skeleton makeup on and were waiting our turn to lead a tour of people who came drunk to school on the weekend to watch the “freaks” take them through the haunted house. When we kissed, I felt like I was wearing a jean jacket with purple fur and hearing Taylor Swift for the first time. But, instead of the voices from behind the bathroom door, the call was coming from inside the house. It was through others that I began to question my confidence, and it was through myself that I made a deal with shame. This shame about what felt correct and normal to my body became a whirlwind of mango vodka, poetry, smoking inside my bedroom, and having s*x with boys to feel like they worshipped me. I discovered Tumblr and Kate Moss and diet pills. I started to talk back a little to teachers. It felt so good. I was sick of it all; I wanted to run away from myself all of the time. The weight of shame was so heavy it transcends words. It can turn you to stone. I loved writing for the newspaper and getting the leads in many productions, but that was about it. Oh, and I also loved getting drunk. God, I loved getting drunk. I loved getting drunk so much I stayed drunk for ten years.

I liked college. I went to Emerson because it was gay and far-ish away from my shame. I dated diverse, interesting, and kind people. But by now, I was cold, drunk, and scared everyone. I got a little bit of self-esteem back through living as myself, but since my family was in denial and around them, I was too, it was never grounded in reality. My confidence was rebuilt when I started to write for a weird magazine, worked at American Apparel, dedicated my Instagram to the color pink, and had space to cry in collegiate classes without being called dramatic. Juxtaposition became my soulmate—teaching yoga and working in a bar to pay for an apartment and roller skates. I graduated with a degree in acting and left for Los Angeles, California. When I got to LA, I lived with the coolest person I’d ever known. Grace is a goth and was my sophomore-year roommate. When I got taken to the hospital in September for throwing up vodka on the walls, just a few weeks into my sophomore year, she filmed me from under the door and told me she “knew we were going to be best friends.” She is a psychic and was right. My days with Grace consisted of just that, grace—a type of West Coast grace I had never known, one built from rehab centers and authenticity. Grace smoked weed, and we skipped class when our magic eight ball told us not to go. Instead, we walked around the Boston Commons as she fed squirrels and never made me be anyone else. She never tilted her head or kept her words stuck inside when I told her about my crushes. Grace liked to find single mothers on Facebook, buy them diapers, and host them in her dorm room for the day along with their babies. When I moved to LA to live with Grace and her father, we did whatever we wanted to do. It was silly, magical, and as far away from my shame as I could find. Eventually, I had to go. Going back to what is comfortable and ancient as we so often do in our early 20s. I left, met a boy, moved in with him, and everything was fine. I was a version of myself that was new and should’ve scared everyone, however, for the first time, I felt that my family would now love me without questions. I find the most insidious versions of ourselves feel the safest.

At 26, my shame caught up with me. I didn’t understand why staying in bed all day was all I was capable of. My mother found a therapist for me, whom I’m still with four years later, and she rocked me to my core. When I came to her saying I had to get my career in order, she told me I had to stop drinking. I laughed. Two years in, I wasn’t laughing. When I finally strung together 30 days of sobriety in 2022, the truth came out. I had never fully gotten to live confidently as who I was, and the shame of that person kept me from even trying. With tequila, that person didn’t have to exist. Eventually, my parents and I went to therapy and discussed things in one hour that had been swept under the rug for ten years. I had already come out to them before, but it wasn’t talked about. It still really isn’t, but it’s better. It’s better because I got to say it and permitted myself to dip a toe into self-esteem. What does it feel like to live authentically? It feels like alcohol doesn’t feel as good or necessary. It feels like a deep breath after almost drowning. It feels like not wanting to die. It feels like freedom.

Sarah is the coolest person I’ve ever met in my entire life. We met at the German restaurant where we both worked and were friends for a long time before we kissed on a random Tuesday—those unexpected weekdays that change everything. We connected over books and chain restaurants. I watched Sarah save two customers from an overdose. I fell in love with them slowly and then all at once. Sarah is blonde and a California dream. They have the same type of energy my friend Grace had, which is exclusive to children with strange families from the West Coast and raising yourself. They have letters on their fingers that spell “Lover Boy” and two rings on each side of their nose. Sarah has a pair of Converse that are 3,000 years old. They used to be black, but now they’re a musty brown. If I could go back in time, it would be to see Sarah live the thousands of lives they lived in those brown, limited-edition shoes before I knew them. They are a collection of the most balanced and musical minds that have ever lived. I can’t wait for my Spotify Wrapped this year because it has transformed from being in Taylor Swift’s top 0.03% of listeners to: “You love The Smiths, Nirvana, Elliott Smith, PJ Harvey, Radiohead, and Spare Parts for Broken Hearts; you are also still in the top 0.03% of Taylor Swift’s listeners.” That’s because I didn’t know anything before I met Sarah. I knew everything I knew, but I didn’t know all this new stuff I know now. Before Sarah, I knew the things that were soft and liked me back, but I didn’t know how to like myself. I do now. I know what real self-esteem and confidence are because of how far I ran away from them. I know them because of how many times they were taken from me before I decided to adapt to that feeling of nothing, before my own mental health went into protection mode for the body that held my broken pieces.

I am now 27, nearly a year sober, and closer to the quiet girl I was in childhood. When asked about confidence and self-esteem, I offer the idea that these qualities belong to us from the moment we enter this life. When we reach the point where something has to give, there’s no time for soft reflection on our past—only the urgent need to survive. My drinking, my long-term straight relationship, my intense urge to run were all ways I coped with shame. But before everything finally fell apart, before I left that relationship, looked my parents in the eyes, and put down my drinks, there was always a sense of quietude. It was something inherently mine.

When I chose to stay in the feeling of “I’ve had enough,” peace settled over me. I sensed self-esteem on the horizon; all I had to do was reclaim it with simplicity. Taking our lives back, you see, is not complicated. In my case, I knew exactly what I needed to do: find things that I liked, that were soft, and that liked me back. I see now that the thing I liked most was always me.

Great, so let’s take a few minutes and cover your story. What should folks know about you and what you do?

Right now, you’re catching me in a period of rest. I was (and am) pursuing a career in acting and had some pre-COVID success with a play and a feature film. From 2022 to 2023, I auditioned for 43 projects, but I struggled to connect with my management on who I was and why things weren’t working. I burned it all down and realized I wasn’t taking care of myself. In February 2024, I decided to get sober, which didn’t leave much room for professional pursuits. However, after a long stretch of inactivity since COVID, I auditioned for a Fringe show and gratefully accepted the lead role, feeling a renewed sense of faith.

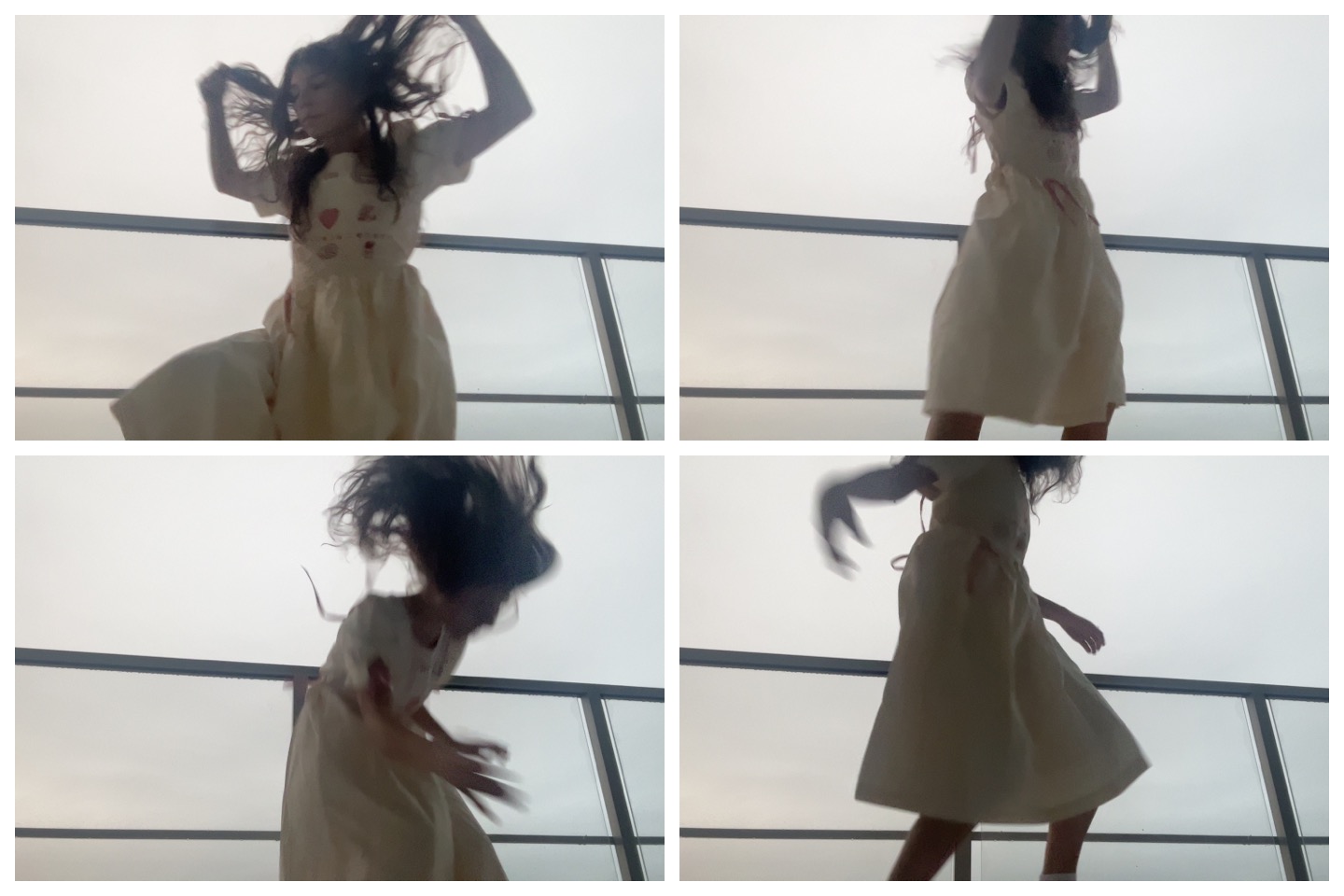

The production was led by John Wuchte and his company, Kickboom Theatre, an avant-garde company that produces original material through highly specific movement and sound—hence the name “Kickboom.” While the show fulfilled me creatively, I’ve found additional joy this year in writing and reading, returning to the softer, more solitary experiences I enjoyed as a girl. I’ve worked to reconnect with my joy in art through writing poetry and by taking Polaroid pictures, especially of people crying. I believe it’s important to capture our humanity in moments of vulnerability when everything seems to fall apart. I also have found catharsis through self-portraits on my camera. I mix the style of Francesca Woodman with the “selfie.”

I’m looking forward to what lies ahead as I continue to grow into this version of myself—a version I genuinely enjoy.

There is so much advice out there about all the different skills and qualities folks need to develop in order to succeed in today’s highly competitive environment and often it can feel overwhelming. So, if we had to break it down to just the three that matter most, which three skills or qualities would you focus on?

Three areas that were impactful on my journey were working in the service industry, intentional alone time, and radical patience. I have worked in restaurants since I was 12 years old—yes, probably illegal—but my first job was working the counter at a beach snack bar. I then went on to work at a diner, a Boston pub, a corporate tourist restaurant, a fine dining French bistro, and now I work in a Los Angeles German bar. I love working in restaurants; it is a real job, and it is enough despite what people may say. I have found freedom, family, and a type of work ethic that nobody could ever take away. I have found a deep understanding of people and how to interact with the varying degrees of human nature. I have learned how to stick up for myself and never let anyone make me feel small (I learned this skill in the bars). This line of work is simultaneously scrappy and generous. As your server, I will make everything yours, and we can be friends. However, if the tide changes and I become less than, chastised, or an object of one’s lack of human decency, I have learned how to tell you that no, you are wrong. No, you are not always right.

Intentional alone time has been essential to my growth. Whether I spend it doing yoga, reading, or taking myself out to dinner, I’ve found it life-changing. In an era of hyper-connectedness that paradoxically leaves us feeling more disconnected, I’ve discovered that I recharge best in solitude. When I’m alone, ideas align and solutions emerge. It can be daunting to sit with oneself, especially without external distractions, but pushing through that discomfort leads to a kind of moving meditation that I can access almost anywhere. If I need to figure something out, I know an hour alone will get me closer to truth. Every answer we need is already inside of us, we just have to be willing enough to listen.

I say radical patience because the waiting will never end. We are always waiting: for the train, the mail, the answer, the job, the bathroom—you name it. I spent far too long fussing internally over not booking work that I began to approach auditions with that same desperation I felt in the waiting. It was impossible to escape. So, I eliminated it. I had an acting teacher tell me that we, as artists, must have seasons of “crop rotation” in order for our plants to grow. The artist must experience life for the art to truly emerge. If you’re just waiting around to hear back from a casting director and then going right into the next audition, there is no time for crop rotation—no break from the waiting. Many people can function like this, but some cannot. The waiting gets too big, and patience becomes obsolete. The space between the waiting is filled with things to distract from it. I decided that I must learn radical patience or stop waiting altogether. So I stopped. I learned patience in simple things before I took on the big ones. Instead of looking at my phone in a dentist’s waiting room, I looked around, read boring pamphlets on gingivitis, and watched a lady braid her hair. I got curious instead of desperate to move through the present moment—the one they say brings peace, where waiting is obsolete. We are here, now. We have always been right here.

How can folks who want to work with you connect?

I am! I have done a lot of solo work and feel ready to put myself out there again. I would love to find people in LGBTQIA+ spaces – whether that be photography groups, writing groups, poetry readings, theatre troupes, script collaboration/acquisition (I have so much material I’ve written), fringe groups, or anything in between I’m open to it all. Connecting through Instagram is best.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jenykale/

- Other: https://vimeo.com/jennygriffin

Image Credits

None – taken by myself

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.