We recently connected with Joan Reutershan and have shared our conversation below.

Joan, we’ve been so fortunate to work with so many incredible folks and one common thread we have seen is that those who have built amazing lives for themselves are also often the folks who are most generous. Where do you think your generosity comes from?

First off, I would like to be much more generous: hunker down more with friends and family who appreciate support, and increase my contributions to crisis arenas in the world. I do my best! To the extent that I am generous, I think it comes from a felt connection to other humans, to living creatures, and to the planet. Life is a miracle, but it seems that we often make it tough for one another in our time between the dramas of birth and death. In any case, for me, helping others in concrete ways, and also supporting the environment and biodiversity, nourish my spirit and enhance my life experience. In my art life I acknowledge with gratitude the opportunities that come my way. And everyday small moments of generosity like a smile from a stranger, just connecting to others with kindness–these feel like soul food and give me joy, which I try to pass on!

Thanks for sharing that. So, before we get any further into our conversation, can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what you’re working on?

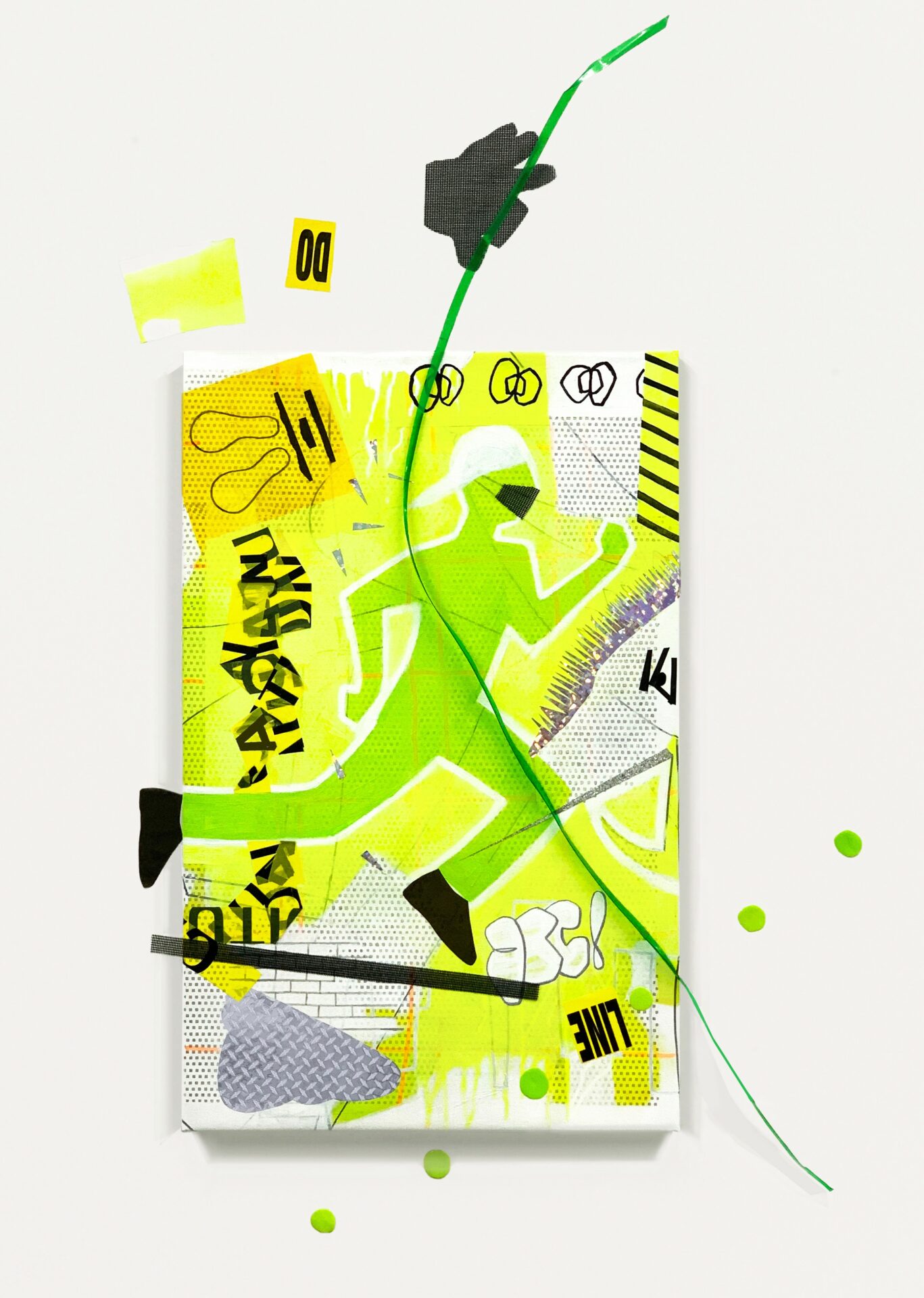

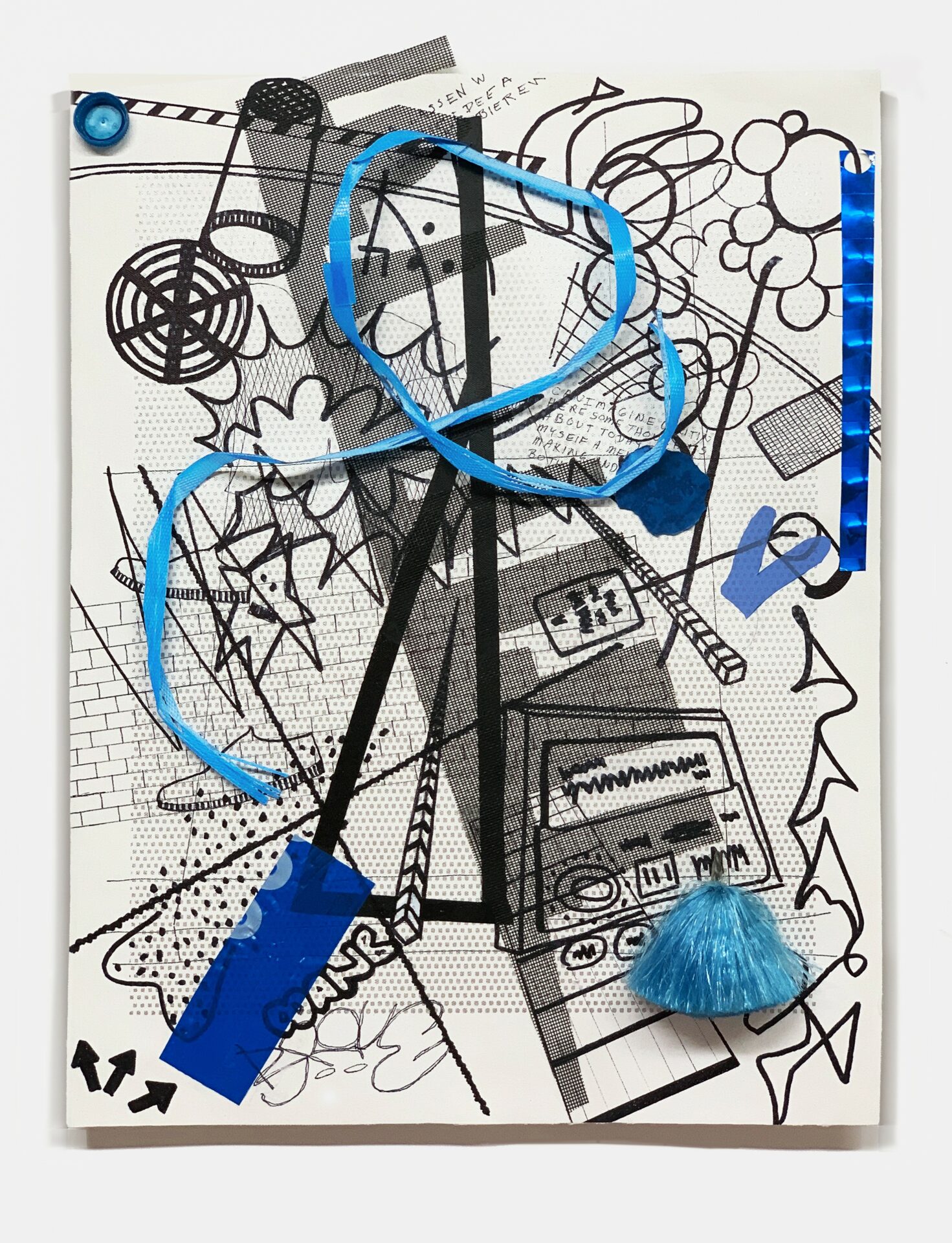

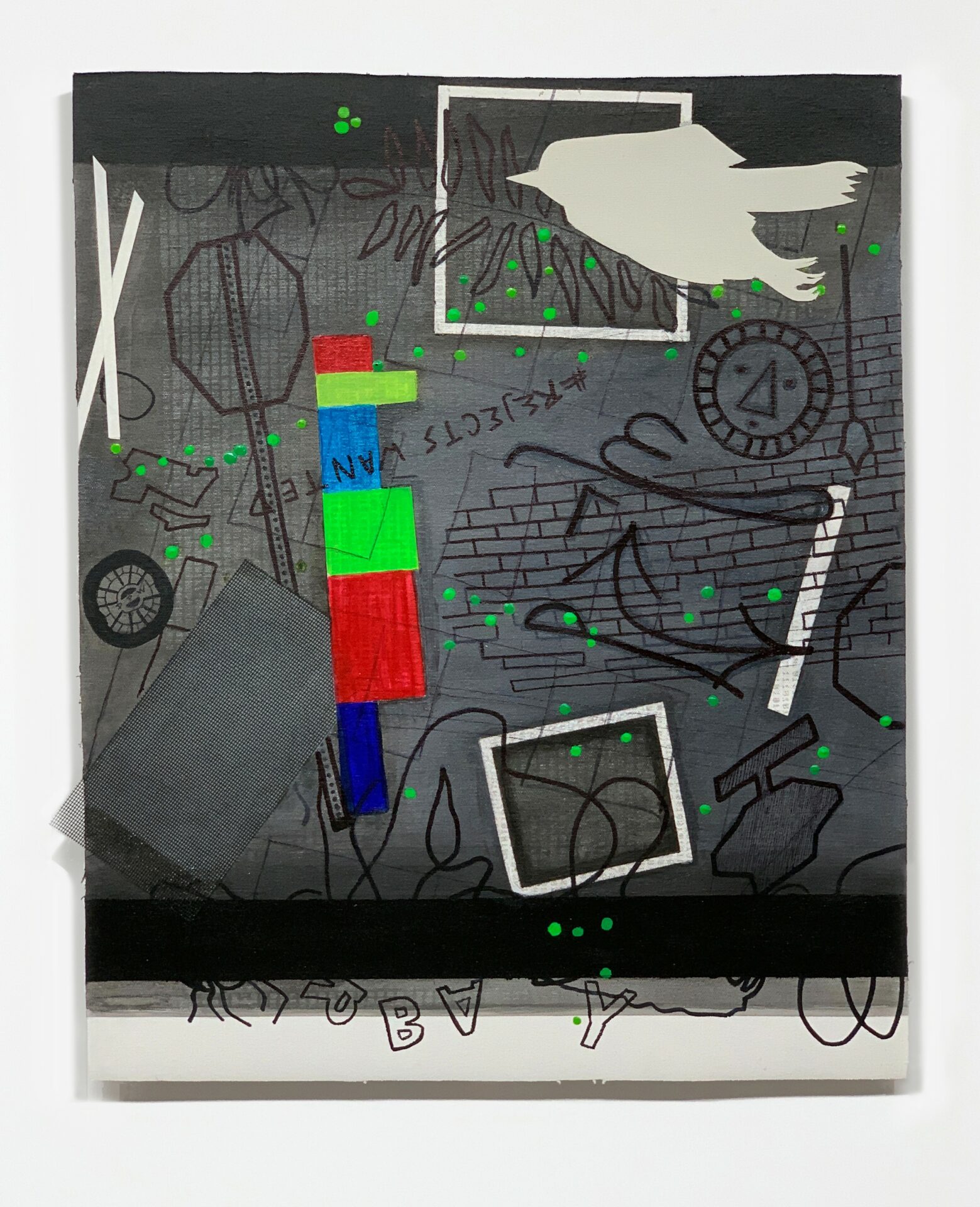

I’m an artist, and I live in Brooklyn, NY and work in Long Island City, NY. I paint brightly colored collage and assemblage paintings based on my experience of New York City. Presently I have work in a group exhibition called “BQE: an Iconography of Queens,” and I look forward to more upcoming shows this year. My artwork these days looks radically different from when I began. This transition really was a “Bold Journey.”

As a painter I’ve always been enamored of landscape and place, curious about the world around me and what lies just beyond my view. I followed the horizon down the block as a kid, and after college I traveled in Europe and lived in Berlin, Germany, while writing a PhD dissertation. All the while my favorite landscape painters–from Giotto, El Greco, and Cezanne, to Hopper and Diebenkorn–were molding my notion of landscape art. When I returned to NYC to teach literature, I painted and sold oil-on-canvas cityscapes, “views” of Brooklyn neighborhoods I knew and loved. In order to widen my repertory, I became a licensed NYC tour guide, exploring the visual kaleidoscope of NYC from atop the moving double-decker bus. It was terrific fun, especially at night!

My entanglement with landscape was not just as an observer, as painter or tour guide, but also as an active participant in city politics. I live near downtown Brooklyn, and starting in the early 2000s a relentless neoliberal building boom altered neighborhoods in a day. Grass roots groups began contesting real estate and planning decisions, creating alternative proposals, and advocating to preserve urban natural resources like street trees and greenspaces. I joined a number of compelling initiatives. Visually, a plethora of 21st Century forms appeared on the street–from contemporary architectural designs, to fluorescent construction signage, flashy advertising, graffiti and detritus. In terms of my painting, I felt that my representational cityscape style—the orderly stack of sidewalk, architecture and sky planes – was out of sync with my times. I wanted to engage with this 21st Century urban friction. How could I acknowledge the disjointed dynamics of the NYC streets in my artwork?

It took years, but I was determined, and over time I grabbed my materials and methods by the bootstraps, did stylistic somersaults and opened my work to embrace high-key color, energetic line and fragmented imagery. I experimented on my own, and studied at Hunter College for a BFA and an MA in art. My go-to source of inspiration was now the vibrant contemporary painting of artists like Charline von Heyl, Trudy Benson, Katherine Bernhardt, Laura Owens and others, who took on modernist aesthetic traditions critically, pushing their limits, and often with humor. Dada Movement artists with their blending of things disparate and incommensurable, often through chance procedures, also became a generative model for me.

Summing it up: I no longer work with conventional oil-on-canvas; my materials include a mix of marker, acrylic, reflective plastic foils and found objects, layered as collage and assemblage. The traditional “view” has also been left behind, and my cityscape is a more abstract space with incongruous parts, perhaps baffling to the viewer, but open to multiple interpretations. I think these new methods align my painting more with the friction between chaos and design, and sense and nonsense, that I experience living in 21st Century New York.

Looking back, what do you think were the three qualities, skills, or areas of knowledge that were most impactful in your journey? What advice do you have for folks who are early in their journey in terms of how they can best develop or improve on these?

Curiosity: Keeping curiosity alive allows me to explore and enjoy what is transpiring in the moment, and it helps me plan for and imagine the future. But it also guides learning from my mistakes and failures: I try to see them as another way to know what my life and world are about. This is more interesting than licking my wounds for too long.

Determination: Maybe I’m just stubborn, but I usually manage to stay with commitments, and trust that somehow it makes sense to persevere. In terms of art making, a mentor once told me to cultivate what I like, be true to it, and that afterwards the meaning would become clear. This advice is not easy to follow when I’m trying new things and leaving security behind. But some inner guide does often seem to move me along.

Humor: Laughter airs out my spirit if I get stuck or sad. And often gratitude and humility come along with humor.

Thanks so much for sharing all these insights with us today. Before we go, is there a book that’s played in important role in your development?

Lauren Elkin’s book Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo is a riveting read of women’s lives in some urban centers of the 20th and 21st Centuries. The character of the flâneur is a usually well-to-do, fashionable, often gay, man, who leisurely savors the urban world at an ironic remove, from the sidelines. The flâneuse is distinctly different–she is involved: Elkin’s women in the cities, foremothers like Virginia Woolf, Agnes Varda, the suffragists, etc. courageously asserted the right to walk the streets by themselves, go to work, demonstrate, and participate in culture. Long story short, Elkin’s text affirmed my personal desire to know the city through engagement with others in contemporary issues, and to let this excitement, hope for change, and “deep landscape” experience transform my painting. Rejecting the idea of cityscape as a “view,” and replacing it with more abstract structure open to the poetry of the absurd, is for me a “queering” of the cityscape. Contemporary art historian and critic Julia Bryan-Wilson thinks of queer as also encompassing the earlier notion of “strange,” a disruption of mainstream expectations and a challenge to the status quo. As a queer artist, this way of understanding my cityscape painting makes sense to me.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://joanreutershan.com

- Instagram: @joanreutershan

- Facebook: @joanreutershan

Image Credits

For the vertical photograph of me you can give this credit: Photo by Izzy Nova