We were lucky to catch up with Kat Bodrie recently and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Kat, thank you so much for joining us today. There are so many topics we could discuss, but perhaps one of the most relevant is empathy because it’s at the core of great leadership and so we’d love to hear about how you developed your empathy?

Empathy is a skill like any other. In middle school, I began taking an interest in my older relatives — the ones who tended to hang back and not say much at family gatherings. I wanted to learn about who they were, what their stories were. I was an engaged, active listener. I started trying to see from the perspectives of people I’d been taught to look down on, particularly poor and homeless people. What did they experience? Who were they? Books, too, showed me that everyone has a reason for their actions, whether conscious or unconscious.

Eventually, I wanted to go to the extreme. What about people who have killed others? What about those who have committed other types of crimes — or those in warfare who commit atrocious acts? A book called Evil: Inside Human Violence and Cruelty by Roy Baumeister showed me that everyone thinks they are a good person with good intentions, and it broke down the myth of “pure evil.” It was eye opening and went a long way in the development of my empathy.

By the time I read the book Crimson Letters: Voices from Death Row in 2021 and befriended three of the co-authors who live on Death Row in North Carolina, I had the capacity to see them as people, to see their humanity, while recognizing the horrible mistakes some of them had made decades ago. (Two maintain their innocence; such is the criminal injustice system.)

Thanks for sharing that. So, before we get any further into our conversation, can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what you’re working on?

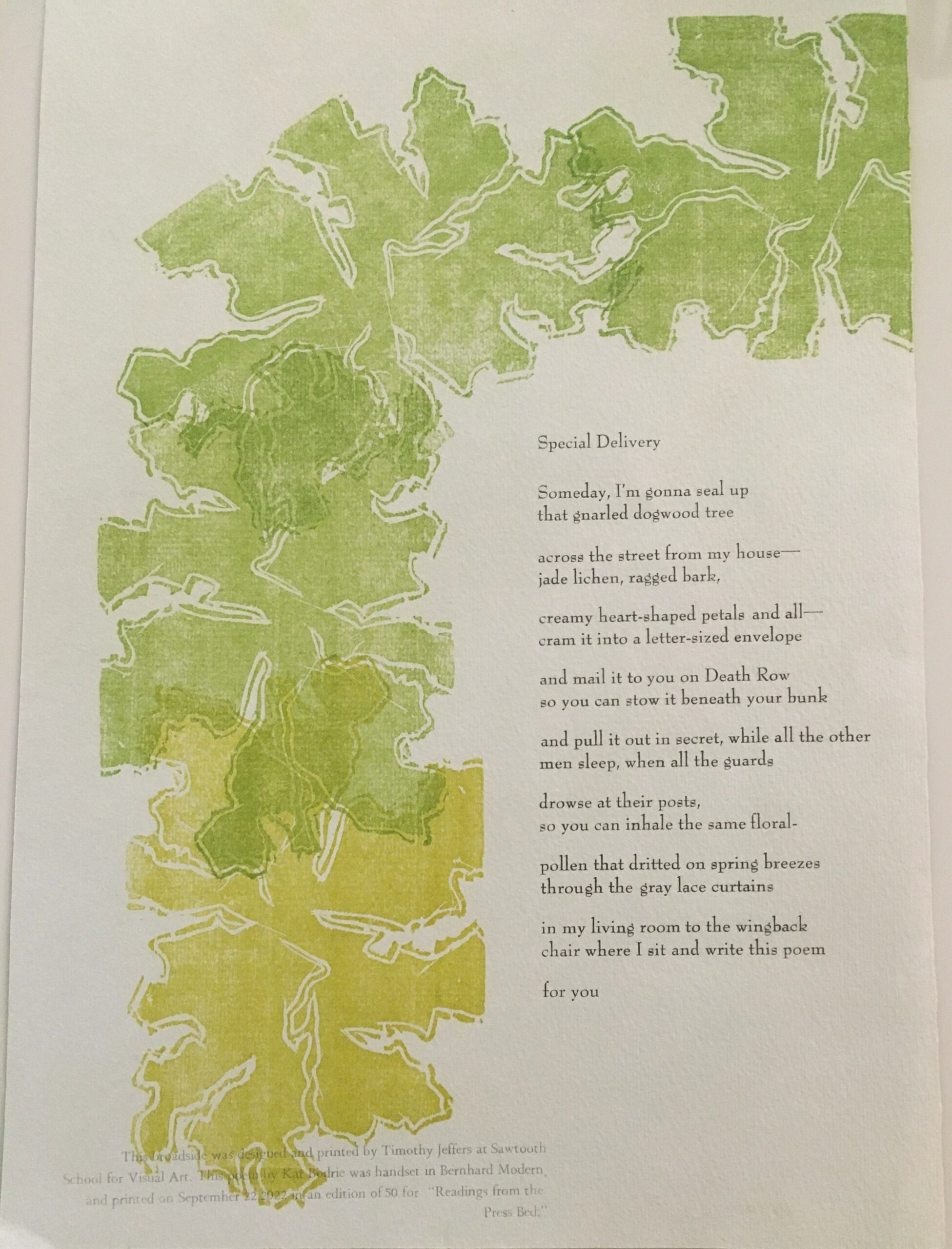

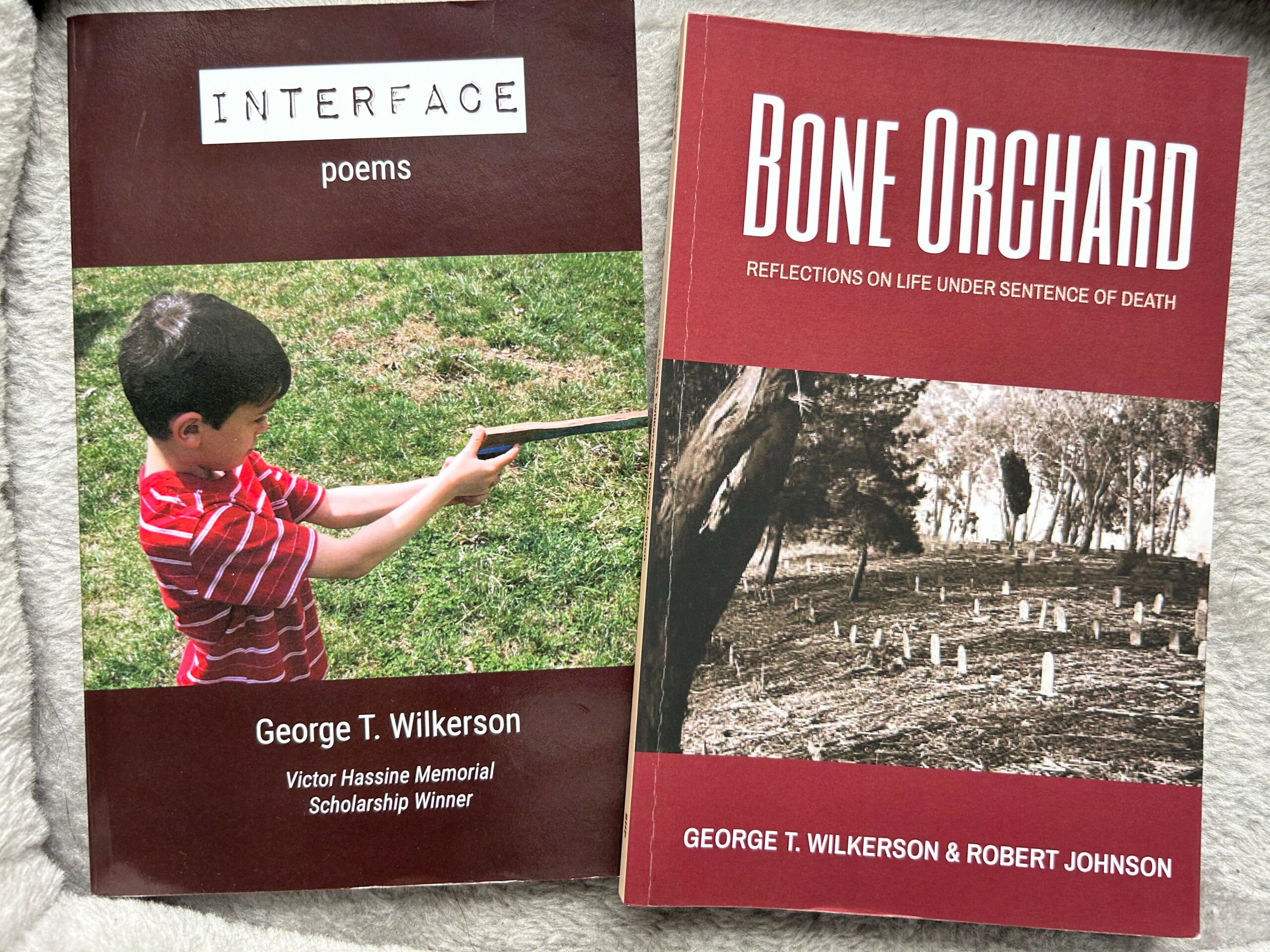

The most exciting and meaningful thing I do is work with incarcerated individuals on their poetry. After I read Crimson Letters: Voices from Death Row in 2021, I contacted three of the co-authors, one of whom was a fellow poet. He and I hit it off, and he’s one of the best poets and critiquers I know, completely self-taught. Our styles of narrative poetry are similar, and we write about some of the same topics. To date, George T. Wilkerson and I have worked on nine manuscripts together, most written individually (like Interface and Bone Orchard, both published by BleakHouse) and two written collaboratively. We even developed a new form of poetry that we call “triangulation poems.” Take any three things you can think of (like cold air, a demon, and clover) and write a poem in which you compare them to each other; this can be done through simile and metaphor. The point is to not only compare each one to the other (three comparisons in all) but to weave them into a cohesive poem.

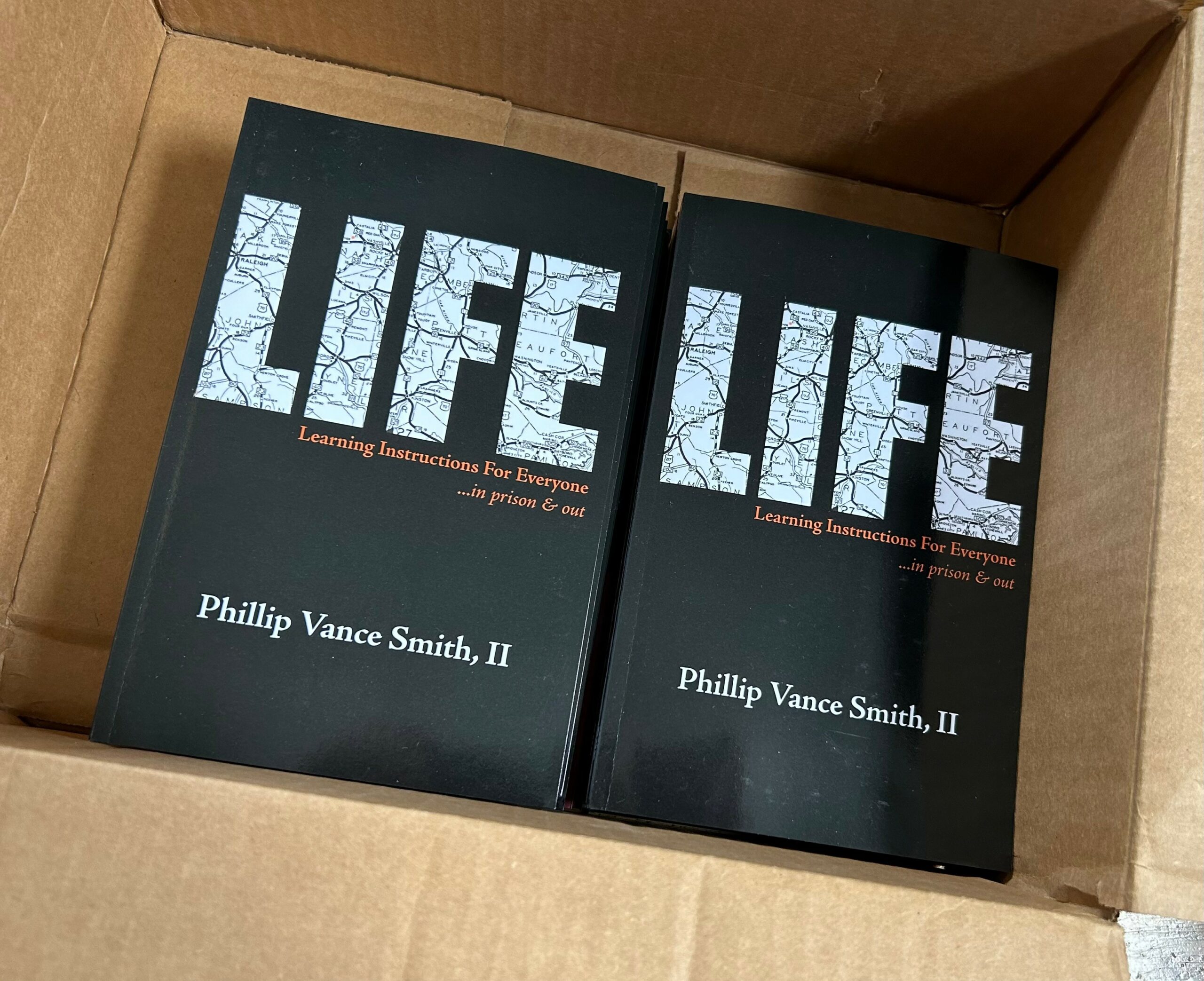

Through my work with George, I became Book Editor with BleakHouse Publishing. We just published a book of poems by Phillip Vance Smith, II, who has life without parole and writes about the conditions of his incarceration, the injustices he and others have experienced, and even the romantic feelings that have blossomed while he’s been inside. (Prisoners, after all, are people, with feelings, wants, and needs.)

I am beyond blessed to know these incredible individuals who are thriving despite their sentences and conditions of confinement. Some think you’re changing their life when you contact and befriend a prisoner, but the truth is, you are also changed, indelibly. It’s a symbiotic relationship.

One of the manuscripts I wrote that I’m trying to publish, What I Wish for You, is about what it’s like to have loved ones in prison, and it touches on the injustices of the carceral system. I want readers to know how it feels to be separated from friends by plexiglass and distance, to be isolated in solitary confinement (which I’ve heard does irreparable damage to your psyche), to face myriad restrictions outside your control, to live in a place that never feels safe. It’s a whole other world in there, with different social rules and etiquette, different conflict management even when it’s nonviolent. George, who’s one of my best friends now, has to context shift every time we talk on the phone. He’s used to apologizing in an indirect way and then “keeping it moving,” as he calls it. I’m used to talking out my problems, listening to the other person’s side, and coming to a mutual understanding or solution. We’ve had our fair share of arguments and know how to deal with them better now. That’s actually something that isn’t in the manuscript, so I clearly have more to write!

Looking back, what do you think were the three qualities, skills, or areas of knowledge that were most impactful in your journey? What advice do you have for folks who are early in their journey in terms of how they can best develop or improve on these?

When it comes to writing, courage, perseverance, and objectivity have helped me most: courage to be honest about even the most difficult feelings and experiences I’ve had (I largely write memoir poetry); perseverance to develop my craft and to continue submitting my work for publication despite the huge number of rejections I receive; and objectivity to remember that rejections aren’t personal and don’t reflect the quality of my writing, and also to see my writing from outsiders’ perspectives so I can fill in the gaps and get my point across without confusing readers.

Every new writer or those new to publishing should know that rejections happen even to the best writers (yes, your favorite writers have received lots of rejections, too!), that finding experienced critiquers and implementing their feedback is essential to the process, and that ultimately, writing is best done for yourself. Even if you publish, forget, for a while, that an audience will see it. When you write the first draft, write it for yourself: because it brings you joy, because you simply must express yourself, and because the act of writing will transform you. This is true, I believe, for every form of art and every act of creativity.

Finally, writers should not work alone. We want to think we’re standalone geniuses, not in need of anyone else’s help, but the best writers work with others, and getting one another’s encouragement and support will boost you in good times and bad. Read books on your craft, take workshops, read books that are in your genre, read books that are outside your genre, get feedback on your work from other writers, implement that feedback, and get to know other writers. Some essential resources include Poets & Writers (magazine and website), Duotrope, Submittable, books like Poet’s Market and Writer’s Market, organizations like Amherst Writers & Artists, and your local and/or regional writers’ groups and clubs.

What has been your biggest area of growth or improvement in the past 12 months?

Last year, I finally recognized that my desire to do good in the world was at odds with my lack of self-love. If I can see the best in my friends who are prisoners, some of whom have made horrible mistakes in their pasts, why can’t I see the best in me?

I’d been seeing a therapist to treat my anxiety and depression, and we’d already been touching on body image and self-image. I’d also heard about self-compassion and radical self-acceptance. I asked her for workbook recommendations because I genuinely love homework and writing exercises. The Self-Love Workbook for Women by Megan Logan has significantly changed the way I talk to myself, think about myself, and treat myself.

Part of my self-care has involved scaling back my commitments because I finally recognized how stressed I was and realized I don’t have to feel that way. Most days, now, I’m able to say that I’m beautiful, talented, useful, and a good friend. I’ve also reignited my spirituality, which involves trusting a higher power — very hard to do for someone who likes having control.

Mental habits are hard to change, so it’s an ongoing practice, like yoga or writing. I’ve had to trust the process and be in it for the long haul. For me, self-acceptance didn’t happen in a day; it’s happened over the course of more than a year through writing exercises, journaling, talking to friends, listening to friends, and meeting with my therapist. And still I lose touch with it and start sinking back into my old mindset. Like many people, my self-hate became entrenched in my teen years, and now that I’m 40, I figure it’s about time to finally love and accept myself. Filling my cup is the only way I can continue giving.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://katbodrie.com/

- Other: https://www.bleakhousepublishing.org/

https://katbodrie.com/georgewilkerson/

https://katbodrie.com/pvs2/

Image Credits

Portrait of Kat: Eric Lynch