Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Marvin Hayes. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Marvin, thank you so much for taking the time to share your lessons learned with us and we’re sure your wisdom will help many. So, one question that comes up often and that we’re hoping you can shed some light on is keeping creativity alive over long stretches – how do you keep your creativity alive?

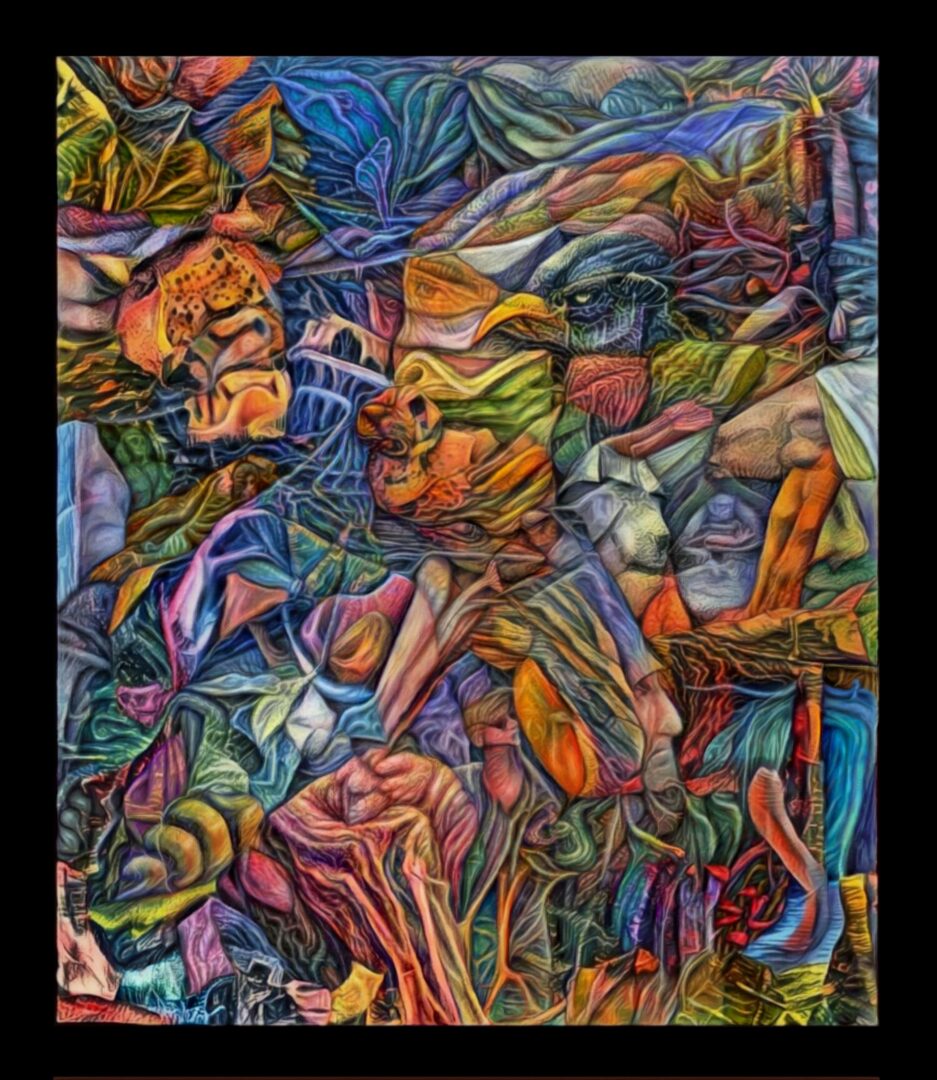

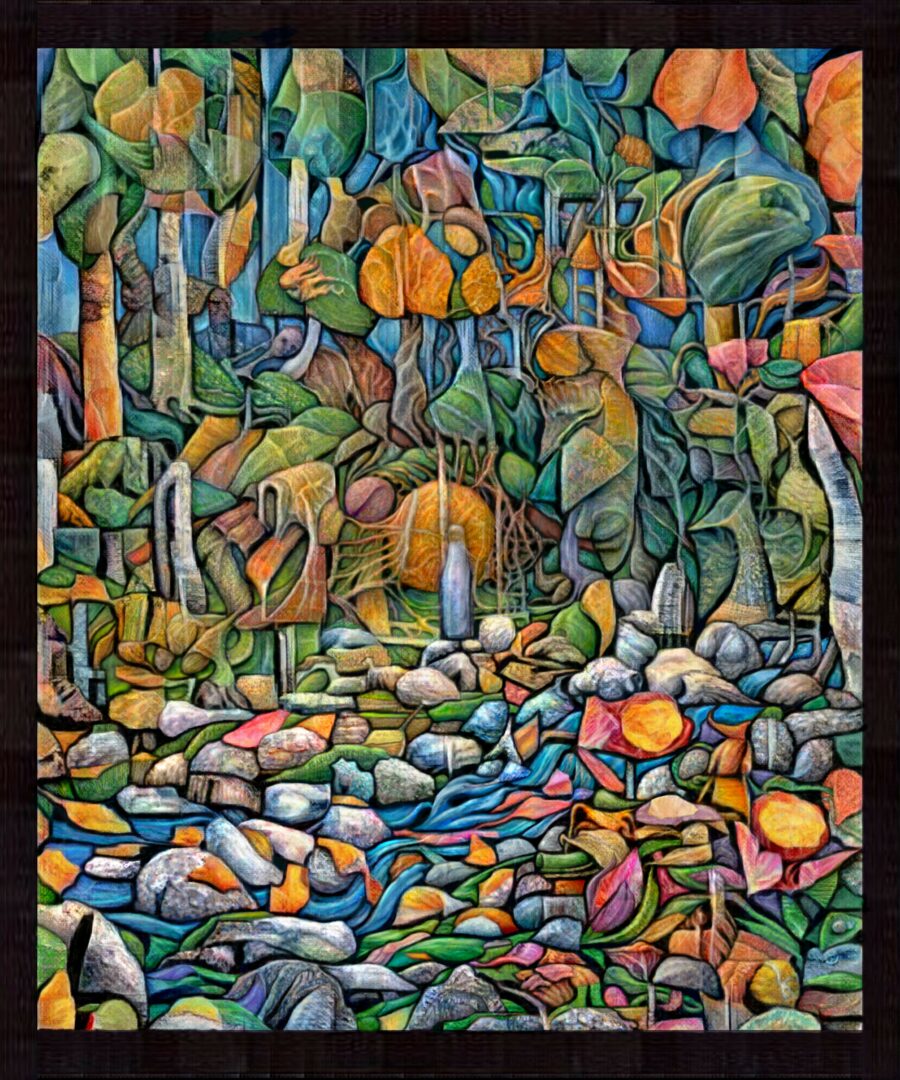

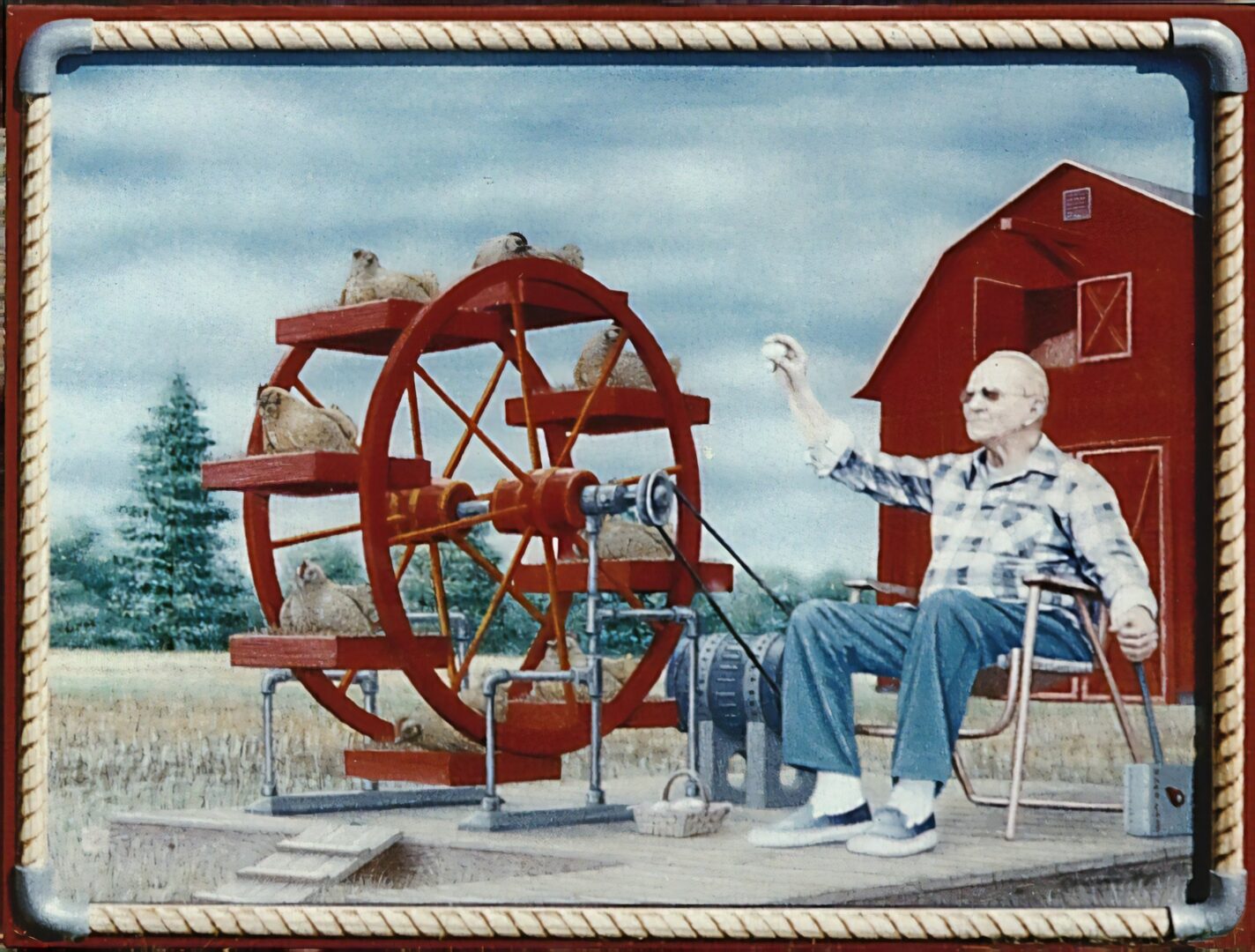

From an early age, I’ve had an intense curiosity about how things work—a drive to explore and dissect what makes them tick. Not just objects, but also the way people think. In my work as an artist, I use my knowledge of media and materials to create the unexpected, often incorporating reverse psychology, opposites, absurdities, ironies, or transitions.

For instance, I might take a watermelon as my starting subject. What is its opposite? Something very dry. What is dry? A desert. A watermelon in the middle of a desert—that would be absurd! Even more absurd? A giant watermelon in a desert.

Another example: I start with the word nonconformer. What is a nonconformer? Someone who steps outside the norm—a person among many who does not conform to the crowd. The thought of a school of fish representing a crowd of people comes to mind, leading to an image of a sardine can packed with fish. All are drab-colored except for one bright fish, happy in its uniqueness, while the others simply exist in their “don’t make waves” existence.

Creativity is deeply connected to interests. Having a wide range of interests and curiosity fuels the creation of media that sparks curiosity in others. I often find inspiration simply by observing—whether it’s other artworks or anything else in the world. The mind tends to regurgitate what it sees, reshaping it into new, interesting concepts. Much of creativity comes down to pattern recognition. Knowing a lot about a variety of subjects creates more opportunities to make connections between seemingly unrelated things.

Ultimately, creativity thrives outside of the comfort zone. The key is to cram as much media into your brain as possible. Look at photography, paintings, drawings. Listen to music, try new foods, read books. Every experience—everything you see, hear, and do—becomes fodder for creativity.

Thanks, so before we move on maybe you can share a bit more about yourself?

It seems like I’ve always been an artist. I first realized this when, at around six years old, I started using ink pens on nylon parachute material from my mom’s sewing room. Around the same time, I decided to make myself a pair of tight-fitting gloves. I traced my hands onto some fake leather with a pencil, then cut and sewed one glove. But by the time I got to the second one, I realized my hand wouldn’t fit into the first—an early lesson that art, like life, is about making mistakes in order to learn. Or better yet, watching others make mistakes and learning from them!

The idea that some people are simply born with talent is a myth. By the age of nine, I was considered an artistic child prodigy, but no one is born with a fully formed skill set. People may have a natural inclination for certain abilities, but it takes hard work and time to develop and refine them. Art has always been my obsession—a means of communication. I’ve never thought of myself as a strong verbal communicator. Media and art have always been my preferred language.

Over time, I made a point of trying new mediums. I started mostly with drawing, despite having no formal art education—mostly black-and-white pencil work, some colored pencil, and pastels. Around high school, I transitioned into painting with acrylics and oils. I’ve never struggled with shifting between mediums. When I started sculpting, it felt like a natural extension of my creative exploration. My work often moves between realism, semi-abstract, and surrealism—partly to keep things interesting. I don’t get bored easily, but I’ve never understood artists who stick to one style for their entire careers. Personally, that would feel stifling. I enjoy working in multiple mediums and styles, which tends to confuse the art industry; they prefer continuity, whereas I am more multifaceted. If I had to conform to a single medium or style, it would feel like working on an assembly line—or being imprisoned.

Lately, I’ve been considering writing children’s books and other types of stories. I’ve compiled outlines for several stories that I find really interesting. One of my favorites is a story about a teenage detective—a dark comedy about a boy genius whose parents have gone missing and who is now being raised by his aunt. Think of it as a blend of James Bond and Harry Potter, with a touch of The Addams Family.

If you had to pick three qualities that are most important to develop, which three would you say matter most?

Persistence, curiosity, and an understanding of how things work form the foundation of most—if not all—talent. One lesson I wish I had learned earlier is that structural knowledge is the core of most media. For instance, a painter should understand anatomy, perspective, and color theory. Talent is often less about innate ability and more about a deep structural understanding. Recognizing the underlying frameworks of any discipline transforms raw skill into refined artistry.

A musician, for example, benefits immensely from studying the theory behind harmony, rhythm, and composition. These principles allow them to move beyond intuition and craft complex, expressive pieces with intentionality. Similarly, a writer thrives when they understand narrative structure, character development, and pacing—elements that ensure their storytelling is not just expressive but compelling.

In every field, foundational structures serve as both a launchpad and a guiding framework. Athletes study biomechanics to optimize movement, architects master physics and engineering to create stable yet stunning designs, and chefs refine their skills through an understanding of flavor chemistry.

Deconstructing a subject—breaking it down to its core mechanics—is essential to building mastery. Whatever one sets out to do, it is best to first examine its foundational structure—the underlying principles that govern its function. Mastery is not merely about repetition or surface-level skill; it is about dissecting the essential components that shape a craft. The deeper one grasps these structural foundations, the more freedom they have to innovate and push boundaries.

Do you think it’s better to go all in on our strengths or to try to be more well-rounded by investing effort on improving areas you aren’t as strong in?

I learned well into my artistic journey that avoiding certain skills—simply because they seemed uninteresting or difficult at the time—was a mistake. Take anatomy, for example. I started out more interested in scenery, surrealism , monsters , animals, and insects—anything but people. I had little desire to draw or paint the human form and thought, Why learn anatomy if I rarely depict people?

Over time, I realized that virtually all structure is important. That includes human anatomy. Animals and insects have anatomy, too—everything has structure in some form. Understanding these underlying frameworks deepens artistic expression and technical ability, regardless of the subject matter.

Whatever the skill, don’t shy away from the challenging or unpleasant areas. Work on your weaknesses first—then refine your strengths. Always push beyond your limits. Failure isn’t just part of the journey; it’s essential to it. Don’t avoid failure—embrace it! Because from failure, success takes root.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.redbubble.com/people/marvinhayes/shop

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MarvinHayesArtist/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCYkA-eLdcVSK8a41O3ub-dA

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.