We were lucky to catch up with Nick Brito recently and have shared our conversation below.

Nick, so excited to have you with us today. So much we can chat about, but one of the questions we are most interested in is how you have managed to keep your creativity alive.

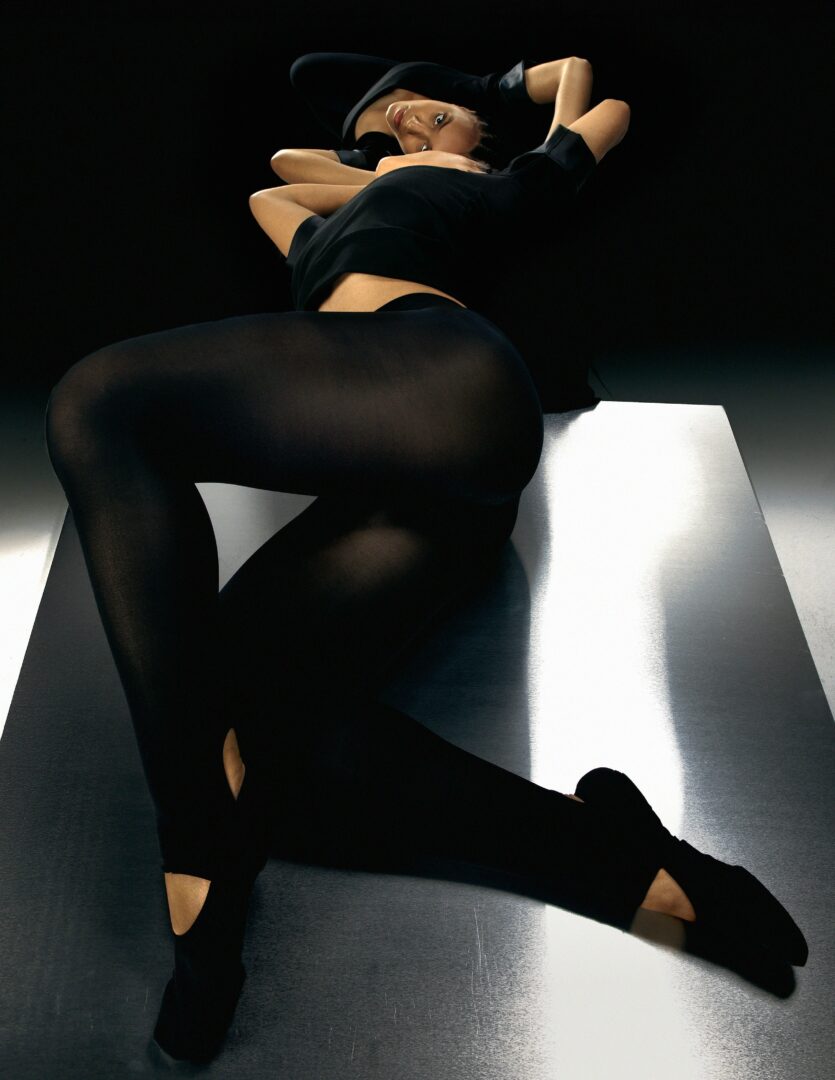

I keep my creativity alive by staying curious and allowing myself to be a beginner—over and over again. Whether I’m working with dancers, experimenting with video, or even just watching light move through a space, I try to stay open to my external surroundings. I collect images, sounds, text—sometimes without knowing why—and trust that it’ll make sense later. It’s also important for me to move my body. I’m not someone who can stay still behind the camera—I use my hands, my legs, my whole frame when I work. I’m constantly adjusting what’s in the shot, shifting light, or stretching to get the angle I see in my head. There’s something about that physical engagement that keeps me present. It reminds me that creativity isn’t just about ideas—it’s about motion, energy, and instinct.

Thanks, so before we move on maybe you can share a bit more about yourself?

Simply put– I take pictures, and I sometimes make videos. The “why” is where it gets a bit more complicated.

Around the age of thirteen, I became increasingly aware of my own mortality. I sensed that at that moment, my life would begin to move faster, as if time itself would suddenly shift into high gear. I began to find refuge in digital spaces like Tumblr and Flickr where i’d find images that were unassuming and often liminal in their visual language. Oftentimes, these images could only be found in the deepest corners of the internet so it would take hours to find them, it became ritualistic and almost medatative. I was mechanically inclined to the process of archiving, curating, and reposting them to my blog and I began to accumulate a following of people that shared a similar interest, though I’d never know for sure if they shared the same fear of being mortal.

A year later I worked up the courage to start taking pictures. I managed to save up enough money to buy my first SLR camera and a cheap 35mm film pack from CVS. I knew that If I wanted to get serious about photography, I needed to start with analog and work my way up to digital. The technical aspect of photography often eluded me, but after a few failed attempts with several rolls of film, I successfully shot my first editorial completely on film.

It felt natural for me to want to understand every aspect of photography—lighting, color, space, composition. I studied it in both high school and college, reading essays written by critics and art historians who described the camera as a weapon of appropriation. Even our language reflects this: the photographer “captures,” the camera “shoots.” But to me, the camera is no more threatening than a hammer is to a nail—or a nail to a coffin. It’s just a tool. It’s the photographer who decides whether to wield it as a weapon or something else entirely.

I grew up Catholic, surrounded by gilded icons, processions, and the weight of ritual. That upbringing is pretty evident my work—the drama of light, the stillness of a figure, and the tension between mystic and truth. I often depict my subjects with a kind of reverence—as if they were gods, or at least something close. There’s an intentional stillness, a sense of worship built into each image that makes it emotionally charged.

“His Strongest Soldiers,” a year long photo series I made in college, became a way for me to channel the existential questions I’d always been circling. Religion, in this case, wasn’t the subject so much as the vessel—it gave me a structure, a language, to explore the kind of imagery I was already drawn to. I’m currently revisiting His Strongest Soldiers, reworking and expanding the series with fresh eyes. It’s set to be exhibited again soon at Naruki Art Dojo in Brooklyn for the month of July.

Lately, I’ve been shifting toward video work. Right now, I’m directing a documentary series that profiles dancers and performance artists for Project III, a dance nonprofit founded by Kasey Broekema. I was recently appointed as Project III’s Creative Director. It’s been refreshing to be part of something that I’m not entirely familiar with—something that challenges me. Working so closely with movement has been creatively enriching; I’m constantly learning, observing, and finding new ways to translate motion into image.

There is so much advice out there about all the different skills and qualities folks need to develop in order to succeed in today’s highly competitive environment and often it can feel overwhelming. So, if we had to break it down to just the three that matter most, which three skills or qualities would you focus on?

Be curious, ask questions, and never expect a solid answer. That’s the whole point of photography—to stay curious. No photographer has ever taken the same image twice, because there’s always something new to see, something unknown just outside the frame. Over time, that curiosity should evolve. It should get louder, more persistent. That’s what keeps the work alive.

And then there’s learning how to see—not just technically, but emotionally. Understanding light, color, composition—that’s one thing. But learning how to recognize a feeling in a frame, or knowing when to press the shutter because something just shifted—that’s everything. The best way to get better at that is to question everything. question art, question movies, meet new people, and ask them questions. Eventually, you’ll be hungry, and you may make a lot of bad work, but that’s how the good work finds its way through.

We’ve all got limited resources, time, energy, focus etc – so if you had to choose between going all in on your strengths or working on areas where you aren’t as strong, what would you choose?

It can feel really good to go all in on your strengths—euphoric, even. You get into a kind of flow where creating feels effortless, where time slips away. And yes, tapping into your strengths is important. But I’d argue it’s even more important to willingly fail within your weaknesses. That’s where the real growth happens. The things that once intimidated you eventually start to feel familiar, even exciting. Over time, those weaknesses don’t just fade—they transform into new strengths, expanding what you’re capable of and how far your work can reach.

Art, in general, has a lot to do with trial and error. And sometimes, it’s the “error” that gives a piece its’ character. When I’m creating an image, I always leave space for things to go wrong—intentionally. I’ve learned that those happy accidents can become the most compelling parts of the work, the thing that sets it apart. Perfection rarely moves people. But honesty, unpredictability—that tends to stick.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.nickbrito.net

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/nick___brito/

Image Credits

Nick Brito

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.