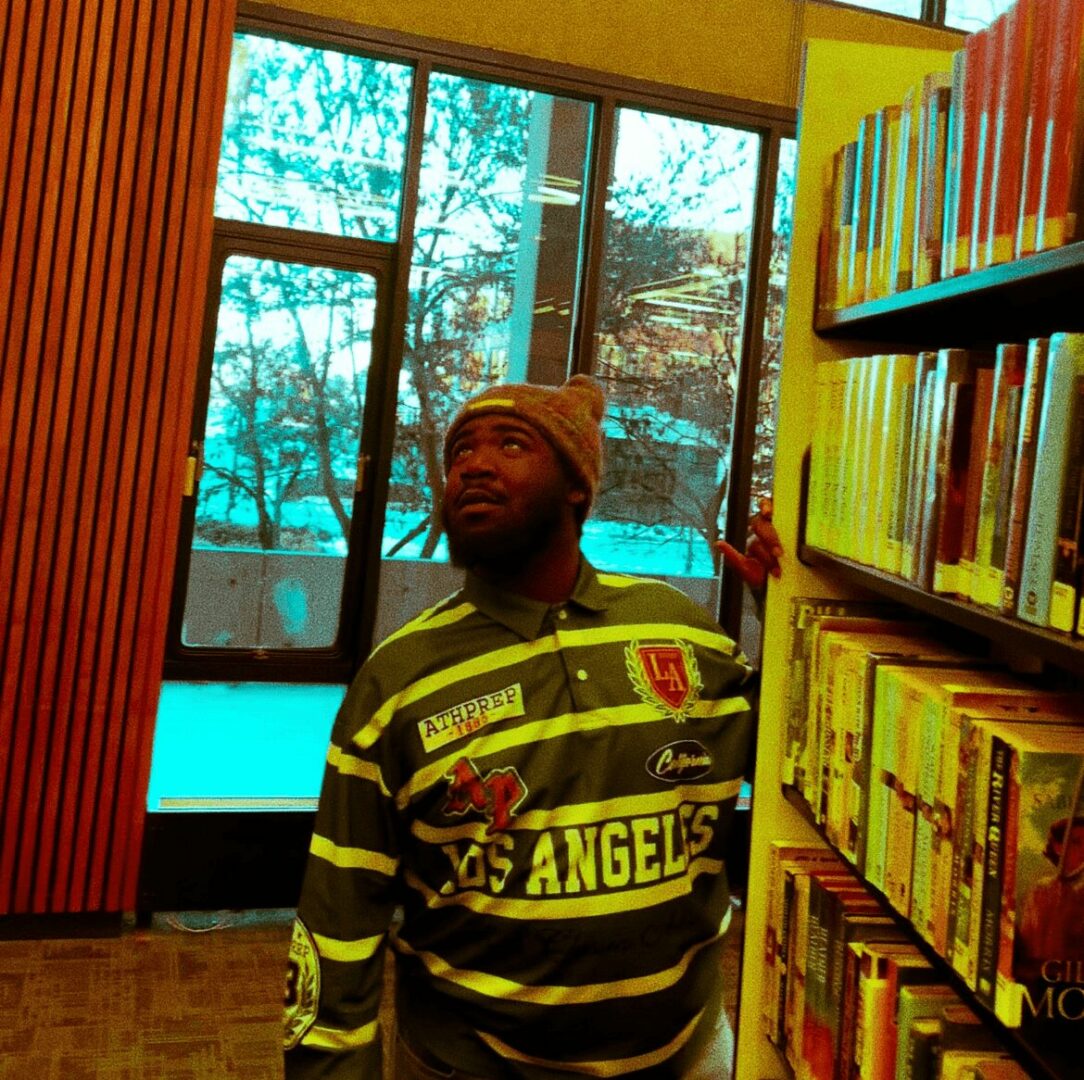

We were lucky to catch up with Oliver Emerson recently and have shared our conversation below.

Oliver, so many exciting things to discuss, we can’t wait. Thanks for joining us and we appreciate you sharing your wisdom with our readers. So, maybe we can start by discussing optimism and where your optimism comes from?

My optimism is not blind. It comes from work, numbers, and seeing people do more than systems were built for.

When I build a ten-year model and see that a city can actually fund fire, police, streets, and parks while keeping housing attainable, that gives me real optimism. The spreadsheet either breaks or it holds. When it holds, I know the story that “it can’t be done” is lazy, not factual.

I also get it from watching residents, not headlines. I’ve seen families, small business owners, and local staff keep communities going with limited tools and uneven rules. If people can do that with bad incentives, I know they can do even more when the financing, covenants, and governance are designed correctly.

As a Black developer in rooms that were not built with me in mind, I don’t have the luxury of vague hope. My optimism comes from proving things out: closing hard deals, fixing entitlement problems that looked impossible, getting local officials to sign off on structures that protect both taxpayers and working families. Every time we lock in a better rule or a stronger covenant, I see that the system can move, even if it moves slowly.

So I stay optimistic because I’ve seen enough evidence that disciplined design beats resignation. If we can balance a budget, codify fairness into policy, and make the math transparent, then the future is not guesswork. It’s something we can actually build.

Appreciate the insights and wisdom. Before we dig deeper and ask you about the skills that matter and more, maybe you can tell our readers about yourself?

I build places that can actually afford themselves.

I’m a real estate developer and principal at Oliver Emerson Development. For a little over two decades I’ve worked on residential and mixed-use projects from raw dirt to stabilized assets. Over time my work moved from “can we build this?” to a tougher question: “can this community fund services, keep housing reachable, and stay solvent over the next 10 years?”

That shift is really the core of what I do now.

What’s unique about my work

I sit at the intersection of development and public finance. That shows up in a few ways:

I don’t stop at the project pro forma. I build 10-year city-style models that include police, fire, streets, parks, admin, and reserves. If the math doesn’t support services, I don’t call it a win. I hard-wire affordability instead of treating it as charity

I’m focused on land banks and community land trusts, permanent affordability covenants, and enforcement mechanics that survive changes in leadership. I speak to both sides of the table. I’ve spent years with planners, engineers, contractors, and lenders. I also work more and more with city and county staff, budget offices, and policy folks. My goal is to give everyone the same set of numbers and the same reality. I treat growth as a finance problem and a governance problem

Entitlements, capital stack, and service delivery all sit in the same model for me. If any one of those is off, the community pays later.

A bit of my story

I came up in development learning the hard way that a beautiful plan doesn’t matter if the budget, approvals, or politics collapse. I’ve had to solve entitlement issues that looked dead, restructure capital in tough markets, and sit with local officials who carry real risk if a project fails. As a Black developer in spaces that were not built with me in mind, I learned to let the work speak and let the numbers lead.

Over time I realized I didn’t just want to build within other people’s systems. I wanted to help design the rules: how we finance growth, how we protect working families, and how we keep cities from over-promising services they can’t afford.

What I’m focused on now

Right now my work has a few fronts:

• Development and advisory

Continuing to lead projects, but with an explicit lens on long-term municipal impact, value capture, and affordability durability.

• City-level finance models

Building and testing playbooks that any city or county can use to evaluate new growth: revenue neutrality worksheets, service-transfer plans, and covenant standards tied to real operating costs.

• Advanced training in public finance and governance

I’m deepening my work through graduate study and professional programs in public finance, urban economics, and development finance. The goal is to bridge practical experience with the tools and language that state and local governments use.

• Writing and thought leadership

I’m developing a book project that traces what it looks like to be a developer trying to found a fiscally honest, permanently affordable city in the 21st century. It’s meant for practitioners, not just policy watchers.

What I want people to know

I’m not interested in models that only work on paper or in slogans that fall apart once the bills show up. My brand is simple: tell the truth in the numbers, design structures that hold up under pressure, and make sure growth actually leaves working families and local governments better off, not worse.

There is so much advice out there about all the different skills and qualities folks need to develop in order to succeed in today’s highly competitive environment and often it can feel overwhelming. So, if we had to break it down to just the three that matter most, which three skills or qualities would you focus on?

1. Knowing the numbers

The most important skill in my journey has been being honest with the math.

If you can’t read a budget, build a basic model, or stress-test a deal, you are guessing.

What helped me:

• Learning financial statements, not just pro formas

• Building 10-year cash flow models and checking what happens when costs go up or revenue slips

• Understanding public finance basics: tax flows, debt service, reserves, and operating costs

Advice for people early in the journey:

• Take accounting and finance seriously, even if you’re “not a numbers person”

• Pick a real project and model it over 10 years: best case, base case, worst case

• Read one city budget and one developer pro forma side by side; ask yourself who is carrying which risk

If you can speak numbers with both lenders and public officials, doors open faster and people take you seriously.

2. Translating between worlds

My work lives between developers, lenders, city staff, elected officials, and residents. Each group uses different language and has different fears. My ability to translate between those worlds has been just as important as any technical skill.

What helped me:

• Sitting in as many different rooms as possible: council meetings, bank meetings, community meetings

• Learning how to explain the same model three ways: one for finance, one for policymakers, one for neighbors

• Writing short memos that answer “What is happening, why it matters, and what you’re asking for”

Advice for people early in the journey:

• Practice explaining your project to three different audiences without changing the facts

• Ask people from other fields to tell you what they heard; adjust your language until it lands

• Watch how senior people in meetings bridge tension without ducking the truth

If you can translate, you become the person everyone looks at when it is time to decide.

3. Staying steady when things get hard

Real projects, and especially anything tied to government, move slower than you want and break in ways you do not expect. Entitlements stall, costs spike, politics shift. Staying steady has been critical for me.

What helped me:

• Treating setbacks as data, not drama

• Keeping a clear long-term goal, even when a specific deal or vote went sideways

• Having the discipline to adjust the plan while holding the standard on quality and ethics

Advice for people early in the journey:

• Expect resistance; don’t take every “no” as a verdict on you

• Build a simple habit when things go wrong: document what happened, update the model, revise the plan

• Surround yourself with at least one person who will give you blunt feedback, not comfort

You don’t have to be fearless. You do need to be willing to stay in the work after the first punch.

If you build real financial skills, learn to translate across systems, and stay steady under pressure, you can grow into work that has real impact, whether you are building a project, a company, or a city.

What is the number one obstacle or challenge you are currently facing and what are you doing to try to resolve or overcome this challenge?

The hardest obstacle right now is trust.

I’m a private developer talking about founding a city, locking in permanent affordability, and setting rules for how growth gets financed. A lot of people hear that and think, “Where’s the catch?” That skepticism is earned by the history of how growth has been done in this country.

So my biggest challenge is proving that I’m not trying to game the system for one project, but trying to design a model that protects residents, local government, and lenders over the long run.

I’m tackling it in a few concrete ways:

• I put the math on the table

I build 10-year service and revenue models and share the assumptions. If the city can’t fund fire, police, streets, and parks while keeping housing reachable, I don’t call it a win. That transparency calms a lot of fear.

• I separate my roles

I’m formalizing conflict-of-interest guardrails: clear documentation of when I act as a developer, when I act as a policy or technical advisor, and what I will not do while in any public or fellowship role. That structure matters to state agencies and local officials.

• I submit myself to other systems

I’m pursuing serious training and credentials in public finance and governance, and I’m stepping into spaces like the Executive Fellowship and doctoral work where my ideas get tested by people who do this for a living. If the model can’t survive that scrutiny, it doesn’t deserve to scale.

• I share credit and control

I’m building this with public partners, community voices, and other professionals instead of trying to own every lever. A city is bigger than one person.

Trust doesn’t come from talk. It comes from rules, numbers, and behavior over time. That’s the work I’m doing now.

Contact Info:

Image Credits

Rock River Current

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.