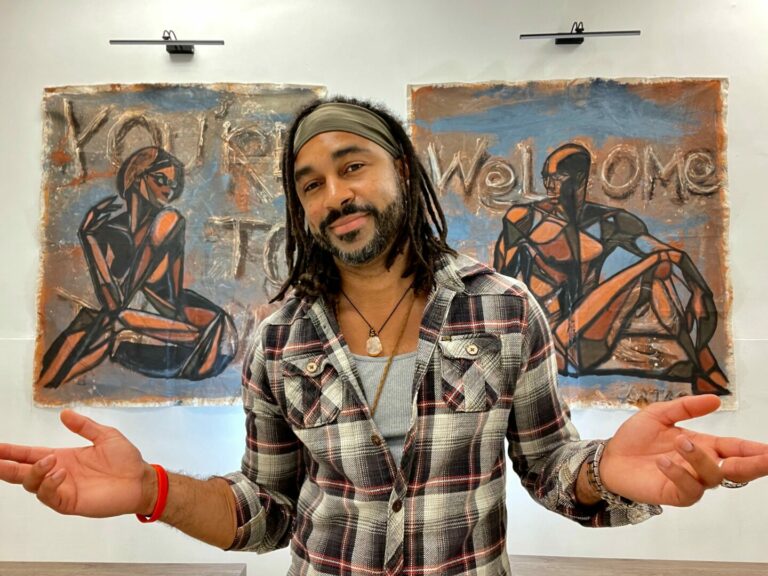

We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Rolondo Talbott. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Rolondo below.

Rolondo, so good to have you with us today. We’ve got so much planned, so let’s jump right into it. We live in such a diverse world, and in many ways the world is getting better and more understanding but it’s far from perfect. There are so many times where folks find themselves in rooms or situations where they are the only ones that look like them – that might mean being the only woman of color in the room or the only person who grew up in a certain environment etc. Can you talk to us about how you’ve managed to thrive even in situations where you were the only one in the room?

I’ve spent much of my life being the only one in the room. The only Black person. The only autistic person.

The only one who experiences the world just a little differently.

When people talk about “the room,” they usually mean a literal space, like a meeting, a classroom, a community, but for me, it’s always been more metaphorical. The “room” represents any environment where belonging is conditional, where presence is tolerated before it’s valued.

For much of my life, I didn’t even realize I was navigating that space with two invisible compasses. My autism wasn’t diagnosed until later in life, which meant I had been decoding the world through both racial and neurological differences without a guide. On the one hand, I was trying to navigate through the social, cultural, and historical layers of being Black. And on the other hand, through the sensory, cognitive, and emotional layers of being autistic.

That duality created a room most people have never entered; a room where you’re constantly reading two sets of rules that were never written for you.

Over time, I learned that being the only one doesn’t always mean you’re the first. Many trailblazers came before me, paving paths that made my presence possible. Their resilience gave me permission to arrive. But there are also times when you are, in fact, both the only and the first. The one building a bridge no one else has crossed yet. Understanding that balance between gratitude and responsibility has shaped how I show up.

Early on, I tried to blend in and mask. I thought effectiveness meant sameness and predicability, that success required proving I could operate just like everyone else. But over the years, I discovered that what actually made me effective was learning to lead with what made me different.

Being Black taught me to observe systems, to see how power moves, who’s invited, and who’s missing.

Being autistic taught me to observe patterns, to notice details, connections, and inconsistencies others overlook.

Together, they became tools for empathy and insight.

I became more effective not by adapting to every room, but by understanding what each room needed to become more inclusive and by trusting that my presence could be part of that change.

Now, when I enter a space where no one looks like me or thinks like me, I remind myself that difference isn’t an obstacle. It’s a contribution waiting to be recognized.

I’ve learned a few things along the way that I would love to share:

Don’t shrink to fit the room. Expand it so more people can enter.

Showing up authentically isn’t defiance; it’s leadership.

Translate difference into value, not apology.

My brain processes the world in its own rhythm, and that rhythm helps me see both risk and possibility.

Redefine success as sustainability, not survival.

Success isn’t about endurance; it’s about being able to show up again tomorrow as yourself.

Being the only one in the room can feel heavy, but it’s also where change begins. Because when we honor those who came before us, and create space for those who will come after, we turn isolation into legacy.

Thanks for sharing that. So, before we get any further into our conversation, can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what you’re working on?

If you asked me what I do, I could tell you I’m a writer, a speaker, and a neuroinclusion strategist. But none of those titles really capture the thread that runs through my work. What I really do is translate difference and turns what the world calls “otherness” into understanding.

My story began long before I had the language for it. I spent years trying to make sense of why I experienced the world in such an emotionally heightened way. Why sounds felt louder, emotions heavier, and patterns more pronounced. For a long time, I thought that was just me being “too much.” Later, I learned it had a name: autism. That discovery didn’t change who I was; it helped me see who I had always been.

Professionally, my work lives at the intersection of story, structure, and belonging. Whether through consulting, writing, or creative projects, I focus on designing systems that reflect the full range of human experience. I believe inclusion isn’t a program, it’s a practice. And the most sustainable change comes from helping people understand why they do what they do, not just how.

Beyond strategy, I write. A lot. Poems, plays, frameworks, children’s stories, each one a different attempt to make sense of what it means to be human in spaces that weren’t built for all of us. My creative work explores the complexity of identity and the quiet power of self-recognition.

What excites me most right now are several projects scheduled to unfold in 2026. The first is the publication of my research paper and theory, The Inclusive Potential Score: a predictive metric designed to evaluate not only the quality of an inclusion effort, but also its systemic priority, resource efficiency, and potential for long-term organizational success.

I’m also stepping more fully into the creative space. Building on my first book of poetry, Corporatysm: Being Black and Autistic in Corporate America, I’ve written a short stage play of the same name that will premiere in late 2026. And as part of “Returning Soldiers Speak”, a project supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities and California Humanities, I’m developing an original play alongside a cohort of veteran playwrights exploring our shared experiences of service, identity, and reintegration.

Each of these projects, in its own way, continues my lifelong pursuit: creating work that helps people see themselves and others more clearly. If there’s a single thread connecting it all, it’s that I’m not trying to change people, I’m trying to remind them that they were never broken to begin with.

If you had to pick three qualities that are most important to develop, which three would you say matter most?

If I’ve learned anything on this journey, it’s that there’s no clean arc from struggle to triumph. The movies like to end with the big speech, the applause, the resolution. Real life rarely follows that script. Many of us will face setbacks that don’t resolve neatly, heartbreak that doesn’t heal the way we hope, and moments where the work we’ve poured ourselves into collapses under the weight of systems that were never built to hold us.

That isn’t cynicism. It’s honesty. And honesty, I’ve learned, is a form of care.

If I were to name three things that have mattered most in navigating this kind of path, they would be: courage, discernment, and community.

Courage, because you will be tested. People will resist change, and some will resist you for daring to name what needs to change. Courage isn’t about fearlessness; it’s about commitment. The willingness to continue even when the outcome is uncertain.

Discernment, because passion without perspective can lead you straight into burnout. Learn to recognize the difference between what you can change and what you must challenge. Push systems, yes, but do so strategically. The more discomfort you create, the more likely change becomes, but only if you stay clear on your purpose.

And community, because this work will break you if you try to do it alone. The right people don’t just cheer for you; they challenge you, ground you, and remind you who you are when the world starts to forget. Not everyone has that luxury, and I know that deeply. But even if you have to build it one person at a time, find your people. They don’t have to look like you, think like you, or move like you; they just have to hold space for you.

So my advice isn’t about chasing the fairytale ending. It’s about staying rooted in the truth that the work of change, whether personal or systemic, and remember that it will be slow, uneven, and often lonely. But if you lead with integrity, find courage in clarity, and let community hold you steady, then even if the ending isn’t perfect, the story will still matter.

Is there a particular challenge you are currently facing?

The greatest challenge I’m facing right now is turning awareness into action. We’ve celebrated neurodiversity as an idea: something to appreciate, discuss, and occasionally spotlight. But the truth is that ideas alone don’t create equity. Systems do. And our systems, from the workplace to legislation, are still catching up to that reality.

Although many of us in the neurodivergent community are employed, an even greater number remain unemployed or underemployed. Not because of our abilities, but because too many workplaces still don’t fully see us. The do not understand the value of how we think, communicate, and solve problems. The barrier isn’t our neurology; it’s the structures that were never designed with us in mind.

That’s why one of my current areas of focus is the Neurodivergent Liberation Act (NLA), a developing initiative aimed at establishing and codifying civil rights for neurodivergent people. The NLA seeks to move beyond the limitations of the Americans with Disabilities Act by creating a framework that recognizes the full spectrum of neurodivergent experiences, not as a deficit to accommodate, but as an identity deserving of protection, respect, and equitable access.

This work is deeply personal to me. It reflects the kind of change I’ve always believed in. Change that doesn’t just make space for people, but redefines what belonging means altogether. Still, the challenge is enormous. Advocacy at both the state and federal levels takes time, persistence, and political will. It also takes a community that believes the fight for inclusion is a shared responsibility, not a niche issue.

What keeps me grounded is remembering that progress rarely looks like victory; it looks like persistence.

I know there will be pushback. I expect resistance. But every movement toward justice starts with someone refusing to accept the limits of what already exists. For me, that’s what this work is — a refusal to stop at inclusion when liberation is possible.

Contact Info:

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.