We were lucky to catch up with Shelly O’foran recently and have shared our conversation below.

Shelly, so good to have you with us today. We’ve always been impressed with folks who have a very clear sense of purpose and so maybe we can jump right in and talk about how you found your purpose?

Before I retired three years ago, I was a high school English teacher who found deep meaning in my career teaching literature, writing, and critical thinking to teenagers. Early on, I taught the top students who were part of my tribe of over-achievers; when they cried because they received a 93/100, I offered tissues and hard-won guidance. Later, I realized that the students who needed me most weren’t those at the top. They were the strugglers who usually received the struggling teachers – not helpful to either as these kids need teachers with the expertise, energy, and drive to reach past the angry armor built by a lack of academic success. So I spent the last five years of my career working with the most challenging students, and I savored small cracks in the underachievers’ defenses. One student thanked me at graduation for dragging him across the finish, adding: “[Expletive], you could have made it worse.” I pictured that engraved on a Teacher-of-the-Year plaque.

My husband, Norm, and I retired not because we wanted to stop working but because we wanted control over our schedules. He was a senior manager at a satellite company with intense demands, and I was devoting 70 hours a week to my students. So we built a house along the Chesapeake Bay and made a major lifestyle change.

We had agreed that a happy retirement meant finding ways to continue making a difference. Trained as a horticulturist, Norm explored efforts to restore submerged aquatic vegetation to the Bay’s threatened ecosystem. I planned to write and volunteer at the local high school. Our efforts came together when he read that restoration of the Bay’s health depends on detailed water quality monitoring data, which is available through expensive automated buoys only in the main channel. Relying on the Internet, he began designing and building low-cost automated buoys using Makerspace parts, planning to place them throughout the watershed. I sketched out ways the project could provide authentic learning for local high school students.

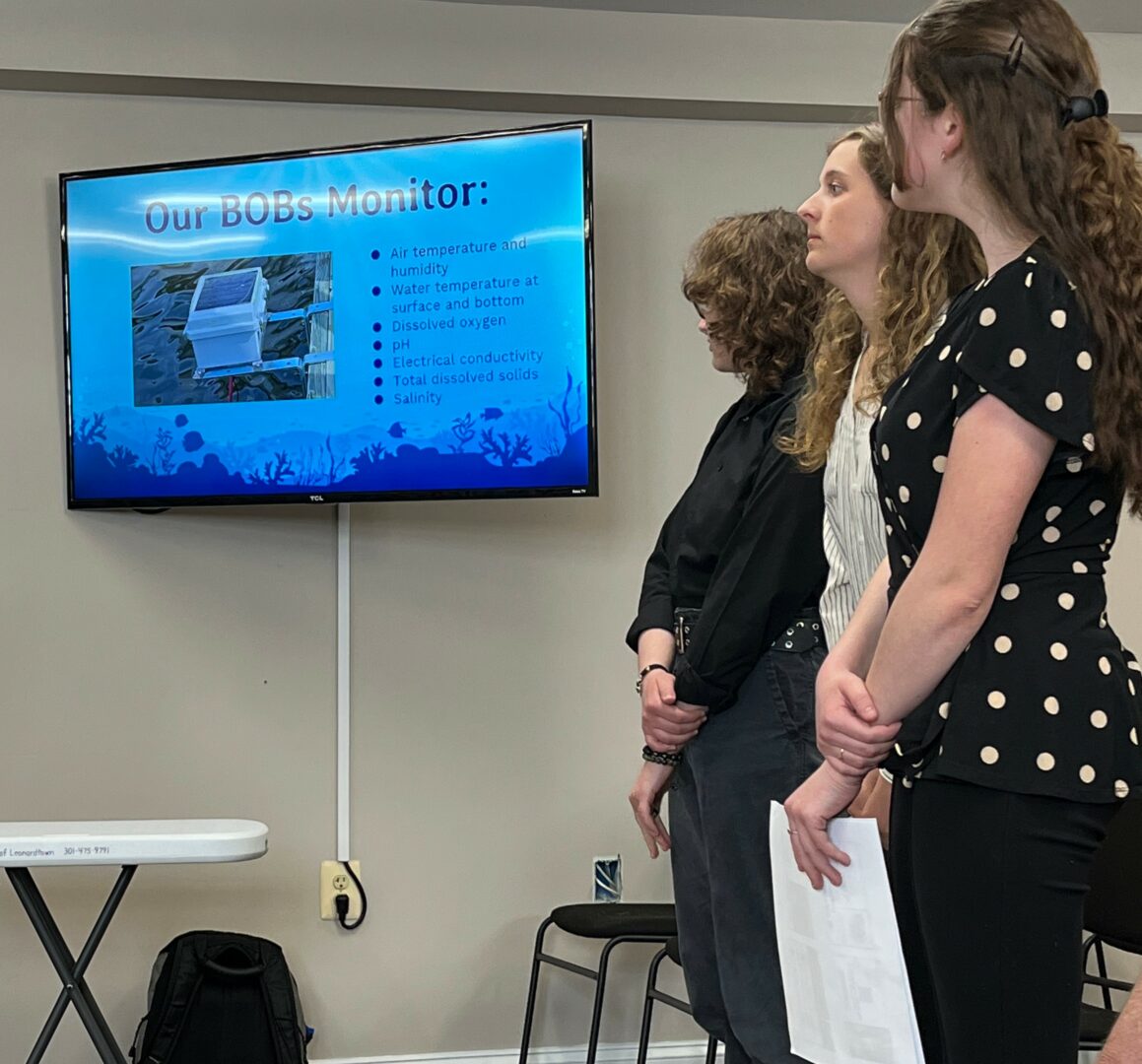

We approached Dorothy Birch, the Natural Resources Management teacher at the local Dr. James A. Forrest Career and Technology Center, and our retirement project began in earnest. For the past three years, we have worked with high school students to design, build, maintain, and publicize our 18 Bay Observation Boxes (BOBs). We also have established a partnership with the St. Mary’s River Watershed Association (SMRWA), placing BOBs at existing and potential oyster restoration sites. Built for about $900 each, our buoys provide continuous monitoring for temperature, dissolved oxygen, pH, salinity, and electrical conductivity, and they send the data to a publicly accessible dashboard every fifteen minutes. This work has been supported by three grants from Chesapeake Bay Trust for Youth Environmental Education and three from the Chesapeake Oyster Alliance for Oyster Innovation.

We have learned that our BOBs’ data is not yet scientifically reliable, so Norm is working on a new design to mitigate the biofouling that largely interferes with the sensors’ ability to take accurate measurements. Rather than dropping the sensors into the mucky Bay watershed, he is learning to filter the water into a chamber lined with LED lights where readings can be taken and then biofouling irradiated.

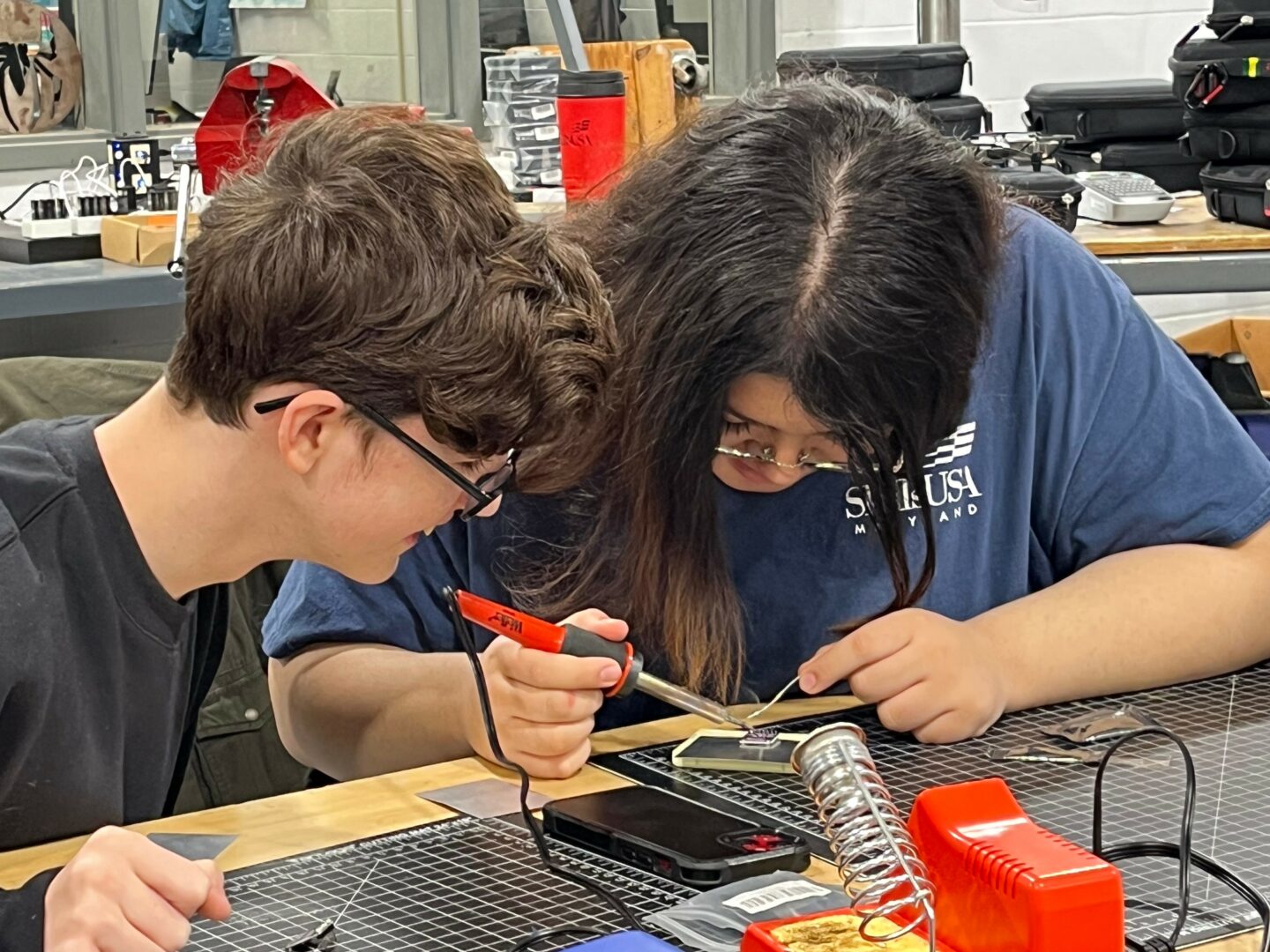

To date, we have provided weekly mentoring to five high school and college students and taught 28 classroom lessons based on this authentic learning project in both Natural Resources Management and Engineering. In fact, the Engineering students are helping us to build a prototype turbidity sensor based on research done in Spain. Turbidity proves difficult to monitor using available inexpensive sensors because they lack reliable results, but we need this information to safeguard oyster restoration efforts, as too much turbidity essentially suffocates the oysters that filter and purify the watershed. The monitors our students are assembling use light attenuation through the water column as a more reliable way to measure this essential aspect of water quality.

It should be noted that neither my husband nor I retired with the exact skills required by this project. He lacks an engineering background but teaches himself through the Internet. I am an English teacher, but this project requires me to use science to work with students. These challenges don’t discourage us. We believe in the project and in our ability to do the work that calls to us.

Norman has a quote by Shirley Chisholm hanging over his workbench: “You don’t make progress by standing on the sidelines, whimpering and complaining. You make progress by implementing ideas.” We use our retirement as an opportunity to do meaningful work and implement ideas to make progress – in the health of the Chesapeake Bay watershed and in the lives of the students with whom we work.

If you had to pick three qualities that are most important to develop, which three would you say matter most?

Because we retired in a rural neighborhood on the lower Potomac River, we lack a large network of nearby colleagues with which to collaborate. Our work depends on our self-discipline, persistence, and sense of optimism to build and sustain the momentum of our project.

We did not retire for an extended vacation, but to do meaningful work on our own schedule. Because nobody now expects us to be at our desks every weekday at 9 am, we must push ourselves past the inertia and excuses and do the work. To overcome our own resistance, we have applied for and received six small grants for this work, and more than the money, these obligations help to keep us focused. We know that soon we will have to write another report and have something to show for the money we have received.

Developing a creative idea is like giving birth – a messy, painful process. It’s easy to lose faith and feel that our efforts are in vain. We look at the large problems driving pollution and habitat loss in the Bay – from climate change to development – and feel tempted to give up our small efforts. But “Sometimes magic is just someone spending more time on something than anyone else might reasonably expect,” according to Raymond Joseph Teller. For us, magic comes from consistency. We can’t Save the Bay all at once or by ourselves, nor can we educate all the students in St. Mary’s County or even at the Career and Technology Center. But we can do a little bit every day, and we cultivate faith that the practice adds up.

This persistence requires optimism. There is never a shortage of people to tell us why our idea will fail, how the effort to make a difference is misguided. Taking action is difficult; criticizing the efforts of others, or ourselves, is easy. When Norman seeks an answer to a coding problem, or a solution to the biofouling, he cultivates the belief in his ability to successfully work through the issue even though he is struggling in a remote garage in rural Maryland. A few years ago, he emailed others engaged in similar work and received help from thousands of miles away in Spain.

This, above all, is what we attempt to teach the students with whom we work: You are stronger than you think, and you have access to the resources you need. Engage in the process. Do the work. As Wendell Berry advises, “Be joyful though you have considered all the facts.”

Contact Info:

- Website: https://sites.google.com/view/bobsmonitors/home

- Other: https://thingspeak.mathworks.com/channels/public?tag=bobsproject

https://cbwins-bobs-dashboard.streamlit.app/

https://smrwa.org/

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.