After years devoted to healing, family, and quiet survival, Nakesa Sineath is stepping back into activism and storytelling with clarity, courage, and purpose. A mother, advocate, author, and emerging trauma and grief therapist, Nakesa shares how the loss of her son Amari reshaped her life—and how she is transforming that grief into education, legislation, and narrative change around filicide. In this conversation, she reflects on reclaiming her voice, centering surviving parents, pursuing systemic accountability, and building a legacy rooted in truth, compassion, and protection for future generations.

Hi Nakesa, thank you so much for taking the time to reconnect and share this deeply meaningful chapter of your life with our readers. You’ve carried many roles — mother, wife, student, advocate — and now you’re stepping back into activism and storytelling. What was the moment you realized it was time to reclaim this part of yourself and your voice?

For a while, I fell back. I leaned fully into being a mother and a wife, focusing on nurturing my marriage, protecting my mental health, and embracing the blessings that had come into my life. I was in a season of building, healing, and simply learning how to receive joy without guilt. But last year, during my pregnancy with my last-born child—my son—and the year that marked a decade since Amari’s murder, something shifted. Even surrounded by love and new life, I felt an unexpected emptiness. It wasn’t ingratitude; it was recognition. I realized a part of me had gone quiet, not because it was gone, but because I had set it aside. That moment reignited something in me. For the sake of my living children and my angel children—especially Amari—I accepted that it was time to pick up the mantle again. To speak, to advocate, to create, and to tell the stories that still needed telling. Returning to this work wasn’t about reopening wounds; it was about honoring purpose. Now, I feel whole again—not because the pain disappeared, but because I finally allowed every part of who I am to exist in the same space.

You released a powerful three-part docuseries sharing your lived experience with filicide and life in its aftermath. What did it take emotionally and creatively to tell your story so openly, and what do you hope people truly understand after watching it?

Telling my story through the three-part docuseries required a level of emotional courage I didn’t know I still had, but it was also deeply intentional. The purpose wasn’t only storytelling—it was education. Filicide is a term that remains under-studied, under-reported, and frequently mischaracterized in media coverage. Even many parents who have lived through it have had to fight for the language to accurately describe what happened to their children. Most news outlets fail to name filicide for what it is. Cases are often framed as isolated tragedies, domestic disputes, or vague incidents, rather than part of a larger, systemic issue that deserves serious academic, legal, and social attention. Through this docuseries, I wanted to contribute to the growing effort among surviving parents who are tirelessly advocating for greater acknowledgment, research, and accountability surrounding filicide. Revisiting the memories, the timelines, and the aftermath required me to engage with my story in a new way. It was entering a deeper level of healing. For the first time, I was able to honor Amari not only through words, as I have done in my books, but through a visual narrative that allowed his story to exist in a living, embodied way. Creating the docuseries gave Amari’s life, personality, and legacy a presence beyond headlines and court records. It allows audiences to see him not as a case, but as a child —my child—who laughed, loved, and mattered. In that sense, the project became more than a recounting of tragedy—it became a lasting tribute and an act of reclamation. My hope is that people walk away not just informed, but transformed in how they understand filicide, how they view surviving parents, and how urgently we must shift the way these stories are told.

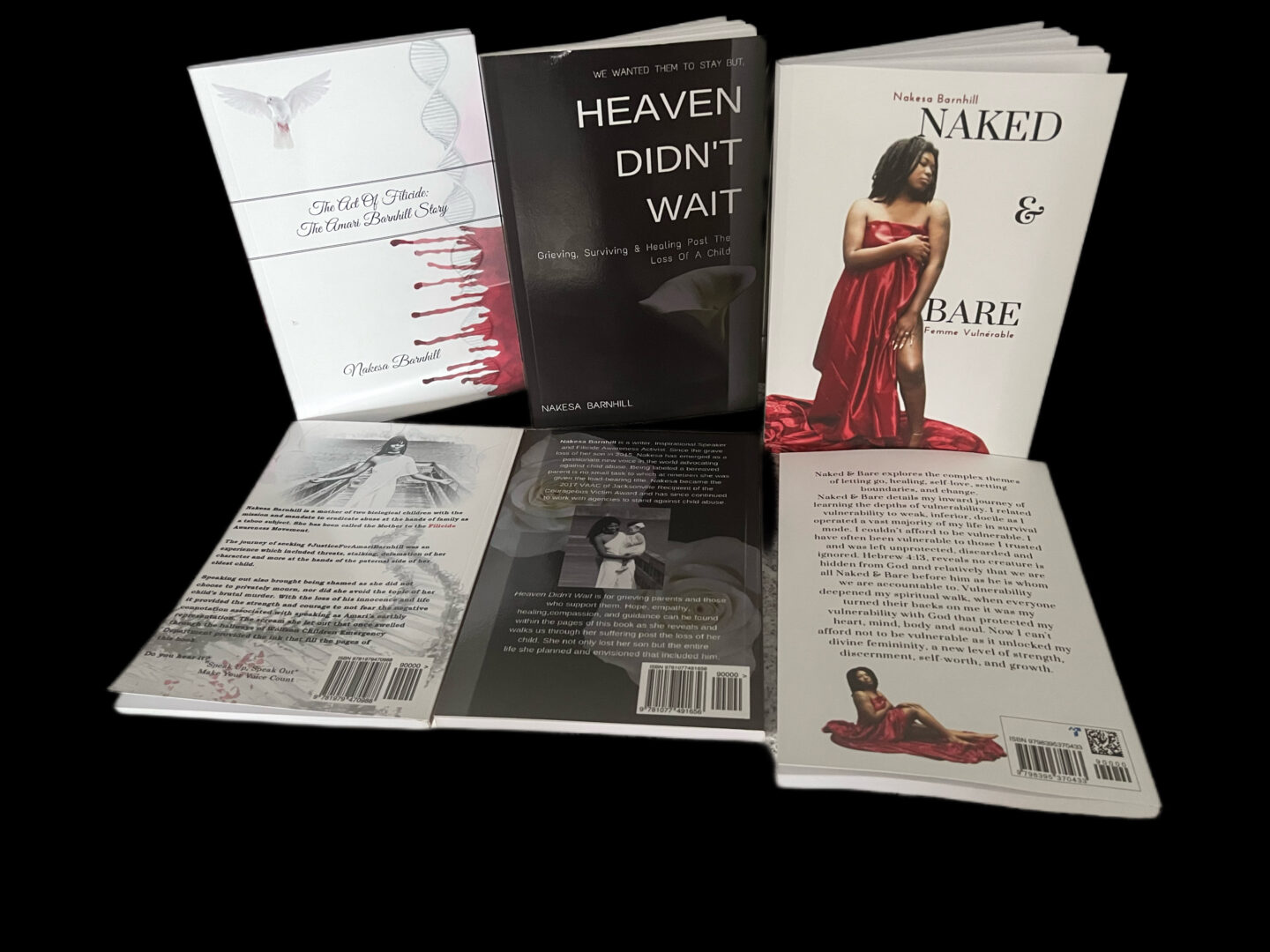

You’re currently working on your fourth book, FILICIDE: Told Through the Eyes of Surviving Parents, alongside other parents with shared experiences. Why was it important for you to center the voices of surviving parents and challenge the narratives often shaped by sensationalized media coverage?

I wanted this book to exist because surviving parents are often spoken about, but rarely spoken with. Media narratives tend to sensationalize filicide, focusing on perpetrators or shocking details while reducing families to sound bites. That approach erases the humanity of the parents who are left behind. By centering surviving parents, I wanted to shift the narrative from spectacle to truth. No one understands this experience better than those who live it. This book is not about reliving trauma for consumption—it’s about reclaiming narrative power, honoring children’s lives, and documenting grief from the inside out. For some contributors, this is the first time their story is being told in their own words. That matters.

In honor of your son Amari, you’re actively working on proposed legislation focused on accountability, awareness, and prevention. Can you walk us through what this initiative looks like and why systemic change is such a critical part of your healing and advocacy?

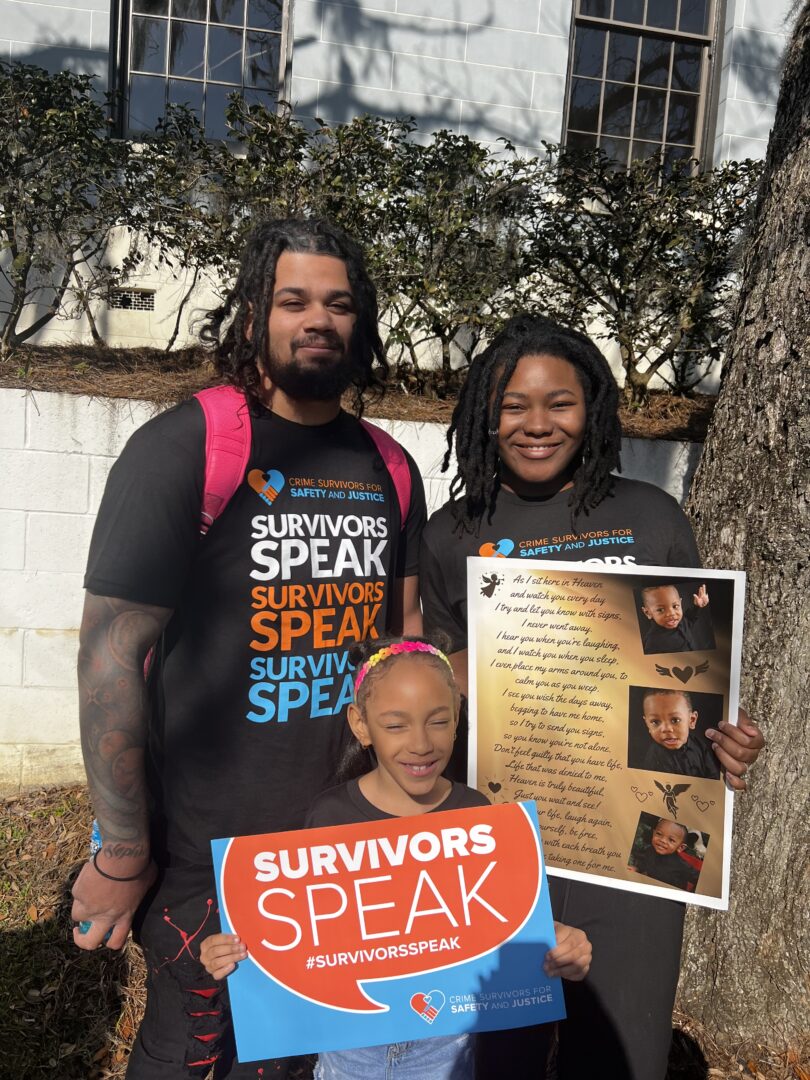

Working on proposed legislation in Amari’s honor is one of the most meaningful ways I’ve transformed grief into action. The initiative focuses on creating a tiered registry of individuals convicted of killing minor children. Similar in structure to the sex offender registry. This registry is intended to increase accountability, awareness, and transparency, while addressing gaps in systems that often fail to adequately protect children and inform communities. Filicide is not only a personal tragedy—it is a systemic failure. Too often, cases are treated as isolated incidents rather than part of a broader pattern that demands structural response. A registry of convicted killers of minor children would serve as both a preventative tool and a public acknowledgment that crimes against children require heightened visibility and responsibility. For me, this work is deeply personal. It is not about punishment alone, but about prevention, education, and protecting future children. Advocacy became a necessary extension of my healing. Healing, for me, does not mean moving on—it means asking difficult questions, challenging existing systems, and ensuring that what happened to Amari is not buried in silence or forgotten by policy. By pursuing this legislation, I am honoring Amari not only through memory, but through impact. If even one child is safeguarded because of this effort, then his life continues to speak beyond his absence.

You’re also pursuing your degree to become a trauma and grief therapist while raising your family and supporting a disabled veteran spouse. How do these personal experiences shape the way you want to show up for others who may be navigating unimaginable loss?

Pursuing my degree to become a trauma and grief therapist while having my family has taught me that grief is never singular—it is layered, interconnected, and shaped by every role we carry. My personal experiences as a mother, student, advocate, and wife deeply influence how I want to show up for others navigating unimaginable loss. Supporting my husband in all of his endeavors, just as he supports me in mine, is what truly nurtures our marriage. It is his willingness to accept all of me—and my willingness to accept all of him—that grounds our partnership. When he joined me at the Capitol in Florida to lobby for change, back when we were newlyweds, I knew for certain I wanted him beside me for all of life’s challenges yet to come. Raising our children is a layered journey of its own. We are navigating parallel parenting and co-parenting with our older two children while raising our younger ones within the blended family we have built together. My family unit is my motivation to keep moving forward—they are the living proof that healing, happiness and hope can coexist with grief. Balancing life as the wife of a medically retired Army veteran, a mother of four, a student, and an advocate while carrying layered trauma has reshaped my understanding of resilience. It has taught me that empathy must be lived before it can be taught, and that true healing happens not in isolation, but in connection. These experiences are shaping the kind of therapist, mother, and woman I am becoming—one who meets others not from theory or as someone who offers clichés, but from lived truth and someone who understands complexity. I want to create spaces where grief is not rushed, minimized, or pathologized—but honored and understood.

As you look ahead — across activism, education, authorship, and family — what legacy are you most committed to building, both for your children and for other families who need hope, truth, and support?

The legacy I am committed to building is one rooted in truth, compassion, and courage. For my children, I want them to inherit a story that acknowledges pain but is not defined by it. I want them to see that their mother did not shrink in the face of tragedy—she transformed it into purpose. For other families, I hope this work becomes proof that their stories matter, that their grief is valid, and that they are not invisible. If my activism, education, and authorship leave anything behind, I want it to be this: a world that listens more carefully to survivors, protects children more fiercely, and allows grief to exist without shame. That is the legacy I am building—not just for Amari, but for every family whose voice has been silenced for too long.

- YouTube Channel https://www.youtube.com/@

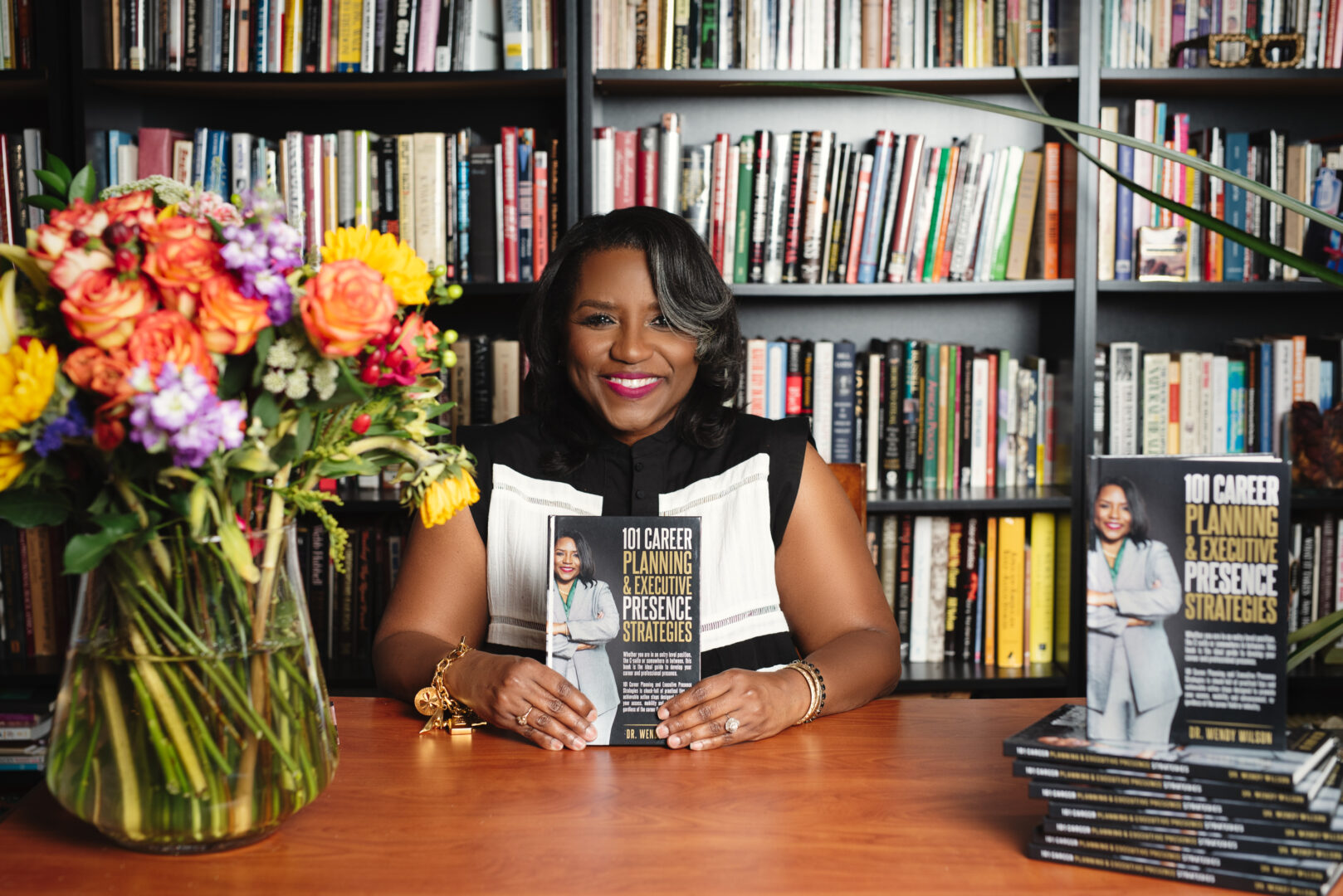

NakesaSineath - Author Page to View/Purchase Books all 3 books: https://www.amazon.com/stores/

Nakesa-Barnhill/author/ B077RPDMJ6?ref=ap_rdr&store_ ref=ap_rdr&isDramIntegrated= true&shoppingPortalEnabled= true - IG: https://www.instagram.com/

life_of_mrs.sineath