Rowynn Dumont shared their story and experiences with us recently and you can find our conversation below.

Hi Rowynn, thank you so much for taking time out of your busy day to share your story, experiences and insights with our readers. Let’s jump right in with an interesting one: What are you being called to do now, that you may have been afraid of before?

I’m finally stepping into the role I’ve avoided for years: becoming the architect of my own research practice. For most of my career, I’ve been the one generating ideas, building prototypes, and carrying the conceptual weight behind collaborative projects—yet I remained half-hidden behind institutions, advisors, or partners. Part of that came from impostor conditioning, part from surviving environments where visibility wasn’t safe.

This year forced a shift. I realized the work I’m doing in neurodivergent design and XR therapy doesn’t belong in the margins of anyone else’s system. It needs its own framework, its own methodology, its own space to grow. That meant claiming leadership—publicly, academically, and structurally—through Mindesign Labs and the developmental psychology research I’m preparing for 2026.

The fear wasn’t about the work itself; it was about ownership. Stepping forward means taking responsibility for the vision, the data, the outcomes, the failures, and the long arc of building something that hasn’t existed before. But the moment I stopped resisting that role, everything aligned: collaborators, opportunities, and a clearer sense of purpose.

Right now, I’m being called to build a field, not just a project. And for the first time, I’m answering without hesitation.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

I’m an artist, researcher, and design psychologist working at the intersection of creativity, cognition, and emerging technology. I spent over fifteen years as a painter before expanding into mixed-media, photography and interdisciplinary work, and that foundation still shapes how I approach everything I build—through gesture, perception, and the emotional architecture of experience. My academic background reflects that hybrid lens: I study psychology with minors in developmental psychology and design, focusing on how different neurotypes process sensory information and how environments can support—or overwhelm—the mind.

My current work centers on Mindesign Labs, where I lead Phase 3 of an XR therapy initiative using VR simulations to support motor control, spatial awareness, and sensory integration in neurodivergent adults. We work directly with day habilitation centers in New York City, testing how controlled, immersive environments can strengthen real-world motor planning and reduce cognitive load for autistic and otherwise neurodivergent adults. The project is still in R&D, but early behavioral data has been promising.

This spring, I’m also beginning development on an AR-based emotional-regulation game for children. It merges my psychology research with my background as an art educator—translating emotional recognition and self-regulation strategies into interactive mechanics that make sense to kids who learn differently.

Mindesign Labs was recently recognized as one of the top neurodivergent-design tech initiatives in the country, which has pushed the work into a new stage of visibility. But at its heart, the mission remains simple: build systems that adapt to people, not the other way around.

What makes my practice unique is that it isn’t split between “art” and “science.” The same questions drive all of it: How do different minds experience the world, and how can we design tools that respond to those differences instead of erasing them? Whether it’s VR therapy, AR tools, or visual work, my goal is always the same—to create environments that are intuitive, dignifying, and genuinely supportive for neurodivergent users.

Okay, so here’s a deep one: What’s a moment that really shaped how you see the world?

One of the moments that shaped me most happened when I was fifteen. I had been kicked out of my home and ended up living in a treehouse behind my school, trying to survive while keeping my grades perfect. It was an extreme situation, but something unexpected happened: instead of breaking, my mind went into problem-solving mode. I learned how to navigate systems, how to observe people closely, how to understand what motivated them, and how to build structure out of chaos. I didn’t have stability, but I had clarity.

That period taught me the world is not built to accommodate people who think differently or live outside the expected narrative. You have to design your own way through it. That mindset has stayed with me through every chapter of my life—art, research, XR therapy, UX work, psychology. It’s why I gravitate toward neurodivergent design: I understand firsthand what it feels like when the environment doesn’t match the person, and how transformative it can be when you build systems that finally do.

It was a difficult moment, but it gave me something essential: the belief that constraints can be redesigned, and that human perception is not a flaw to fix but a landscape to understand.

What’s something you changed your mind about after failing hard?

For a long time, I believed that if I worked hard enough, institutions would eventually recognize the value of my work and support it. I believed in the system. I believed in merit. I believed that if you showed up, delivered, and outperformed expectations, someone would open a door.

It took several painful academic experiences to realize this belief wasn’t just naïve—it was limiting. The “failure” wasn’t my work; it was expecting structures that weren’t built for people like me to suddenly become fair, adaptive, or visionary. When multiple programs collapsed under me—or actively obstructed the work I was trying to do—it forced a reframing: institutions are not the container for the work. I am.

That shift changed everything. Instead of squeezing my research into existing frameworks, I started architecting my own. Mindesign Labs emerged from that pivot—XR therapy, neurodivergent design, multi-sensory research—all built outside the traditional academic gatekeeping that had held me back. And the moment I took ownership of the direction rather than waiting for permission, the work accelerated: recognitions, collaborations, data, progress.

What looked like failure at the time was actually the moment I stopped outsourcing authority and started designing systems that matched my mind, my methods, and the communities I work with. I changed my mind about who gets to validate the work—and in doing so, I stopped needing validation at all.

Sure, so let’s go deeper into your values and how you think. What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

I believe that neurodivergence isn’t a deficit—it’s a different perceptual architecture. And the struggles neurodivergent people face are less about their minds and more about environments that were never designed with their sensory or cognitive patterns in mind. Most people still treat neurodivergence as something to correct or mask. I see it as an alternative way of processing that becomes visible only when the context supports it.

In my work, whether in XR therapy or design psychology, I’ve learned that “functioning” is not an inherent trait—it’s a relationship between a person and a system. Change the system, and the person changes. When you build environments that acknowledge sensory thresholds, spatial processing differences, motor-planning load, or attention variability, people who were labeled “struggling” suddenly thrive. The problem was never them.

This belief shapes everything I build: VR simulations for adults with autism, AR tools for emotional regulation, and even the way I approach art and storytelling. I don’t try to normalize people into narrow behavioral expectations. I try to design worlds where the full range of human perception actually works.

Very few people agree with this fully, because we’re still culturally invested in the myth that there’s one “correct” way of thinking or being. But I’ve seen firsthand how transformative it is when you flip that assumption. People aren’t broken—the systems around them are outdated.

Thank you so much for all of your openness so far. Maybe we can close with a future oriented question. What are you doing today that won’t pay off for 7–10 years?

Most of the work I’m doing today is intentionally long-range. XR therapy, developmental psychology research, neurodivergent design—none of it pays off quickly. These are fields where the real impact shows up years down the line, after enough testing, refinement, and lived feedback to shape something meaningful.

Phase 3 of Mindesign Labs is a perfect example. We’re building VR simulations that support motor control and spatial awareness for neurodivergent adults. The early results are promising, but the true value will come later—once we’ve gathered a significant body of data, published the findings, and turned the system into something that can be scaled across day habilitation centers and clinical environments. That’s a 7–10 year arc. But it’s worth it, because adults with autism are rarely included in therapeutic innovation, and that gap won’t close without sustained commitment.

The same is true for the AR emotional-regulation game I’m developing for children. Designing tools that genuinely help kids understand and regulate their emotions—especially neurodivergent kids—requires years of iteration, observation, and developmental insight. It’s not a fast build; it’s a foundation for an entire class of tools that don’t exist yet.

And in parallel, I’m investing in the academic trajectory that will anchor this work long-term. Pursuing a PhD, building a research portfolio, formalizing methodologies—none of that results in immediate rewards. But ten years from now, it will shape the field I’m trying to build: one where neurodivergent perception is understood as a design principle, not a problem.

Almost everything I’m doing now is for the future version of the field, not the present. The payoff isn’t today—it’s the moment when these tools become standard, when the research becomes part of the literature, and when people who think differently finally have environments that think with them.

That’s the legacy I’m working toward.

Contact Info:

Image Credits

SOLAS Collective Trial – VR Motor Control Task

A neurotypical tester from the SOLAS collective engages with an early motor-control prototype. The session evaluates gesture accuracy, spatial attention, and user adaptability in real time.

NSSR Psychology Lab – Spatial Perception Testing

A trial session conducted in the NSSR Psychology Lab, using VR-based spatial tasks to observe perception, reach accuracy, and motor-intention mapping in a controlled environment.

HeartShare Day Hab – Adult Neurodivergent R&D Session

Prototype testing at HeartShare with an adult neurodivergent participant. These sessions help refine task clarity, motor-planning scaffolds, and sensory load management for real-world applicability.

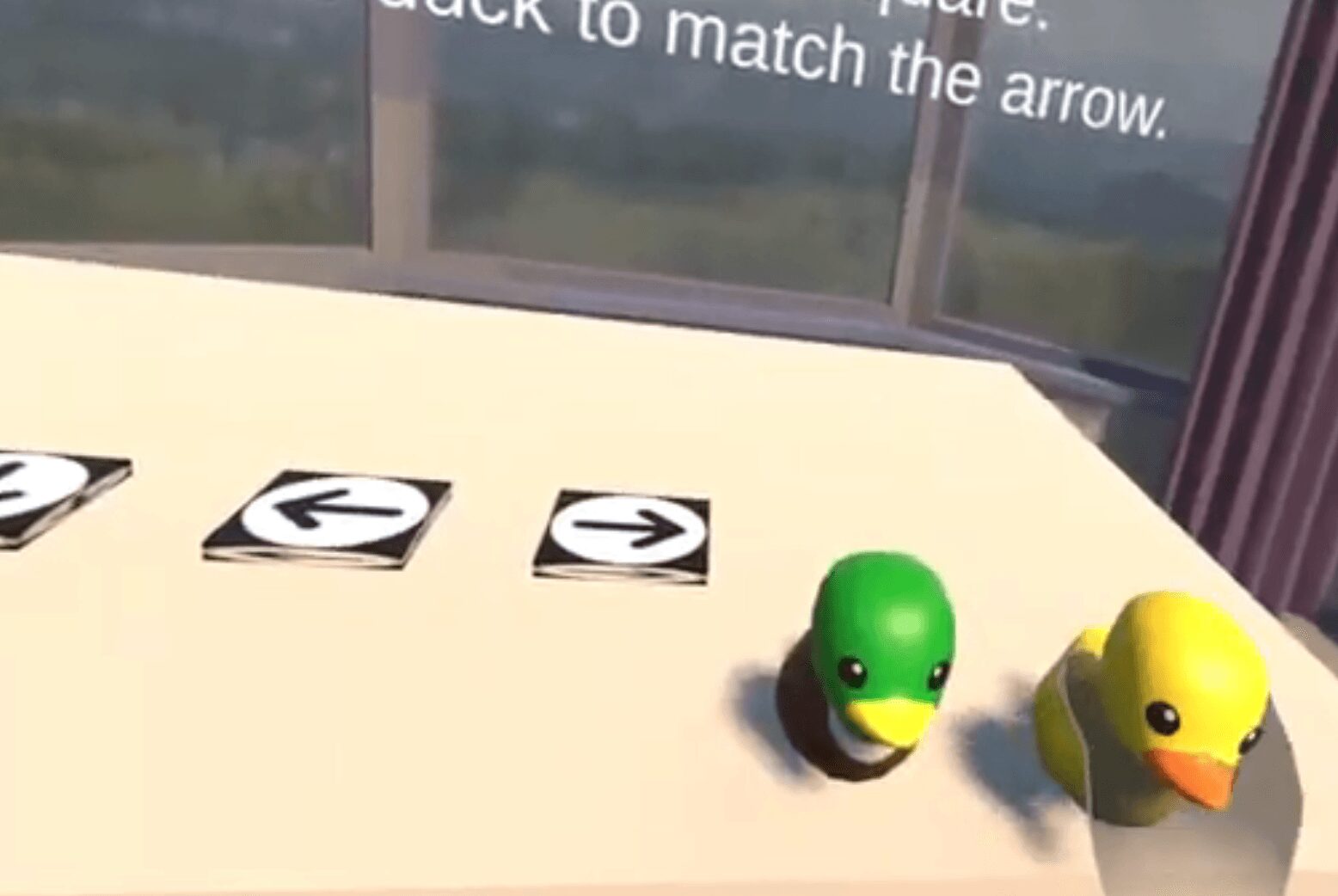

Prototype Environment Screenshot – Directional Tracking Task

Internal view of the training environment used to strengthen motor control and spatial sequencing. Users match directional cues with moving objects to build consistency and reduce cognitive load.

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.