We recently had the chance to connect with Jason Duval Hunter and have shared our conversation below.

Good morning Jason Duval, it’s such a great way to kick off the day – I think our readers will love hearing your stories, experiences and about how you think about life and work. Let’s jump right in? When have you felt most loved—and did you believe you deserved it?

**When I Felt Most Loved**

I felt most loved by my mother, who recently passed away. As difficult as it was to experience her death, the process of caring for her—especially when she had to be placed in hospice—was filled with love. I flew down and spent the last seven days of her life with her, and during that time, there was nothing but love between us.

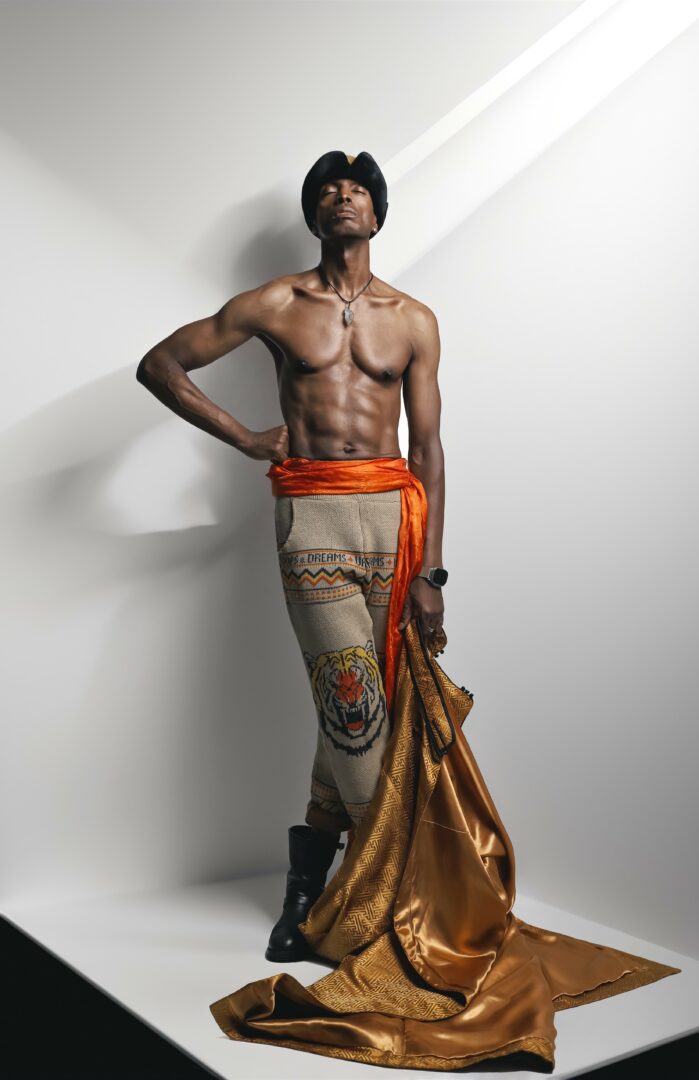

I remember the first day I arrived at the hospice. She was still able to speak a little. When I walked into the room, dressed up as I usually do—very fashionable, with a colorful scarf hanging at my side—she saw me and smiled. I said, “Mom, I’m here.” She looked up, noticed the scarf, and touched it gently, as if to say how beautiful it was. Then she said, “I love you so much.”

She was so happy that I had made it to be with her in her final moments. I had even thought about placing that same scarf with her when we were deciding what she would wear for the funeral, but I decided to keep it. I still have it to this day.

I’ll never forget that moment. I said, “Mommy, you love me?” and she said, “Yes, I love you so much.” I believed her then, and I still believe it now. I know, without a doubt, that my mother loved me deeply—and I loved her just as deeply in return. I absolutely believed I deserved my mother’s love as she deserved mine.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

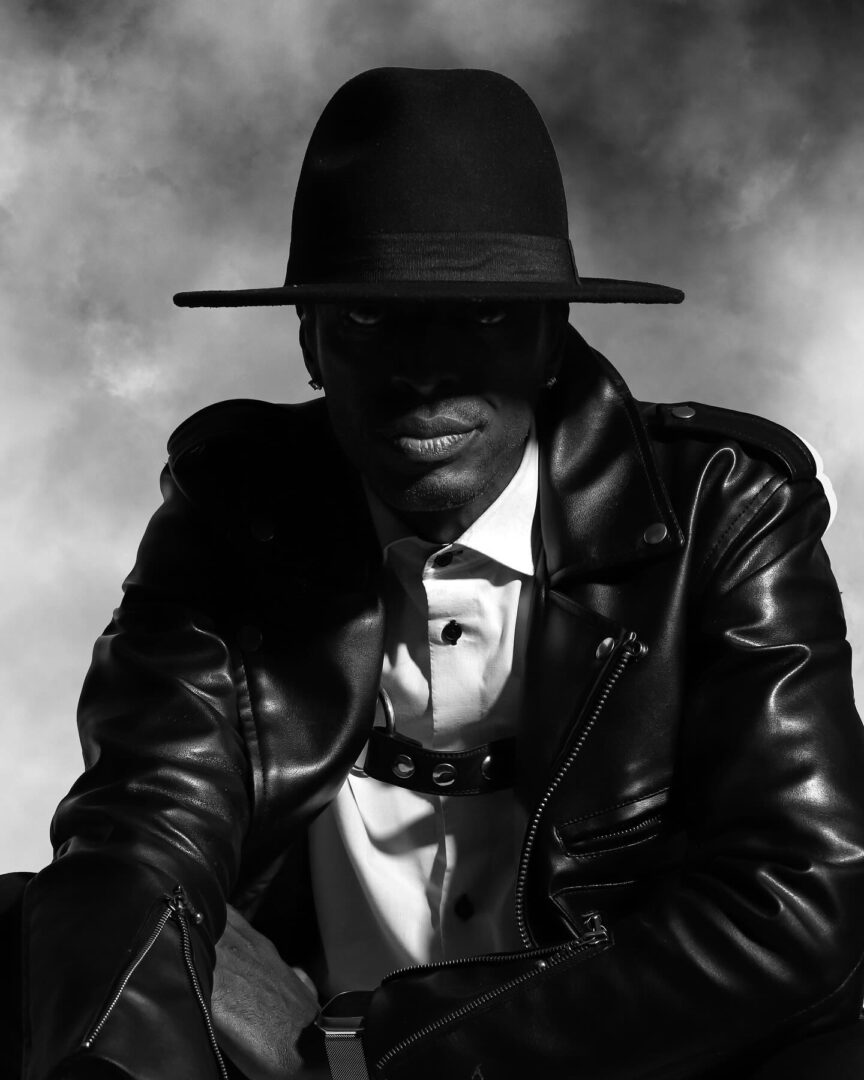

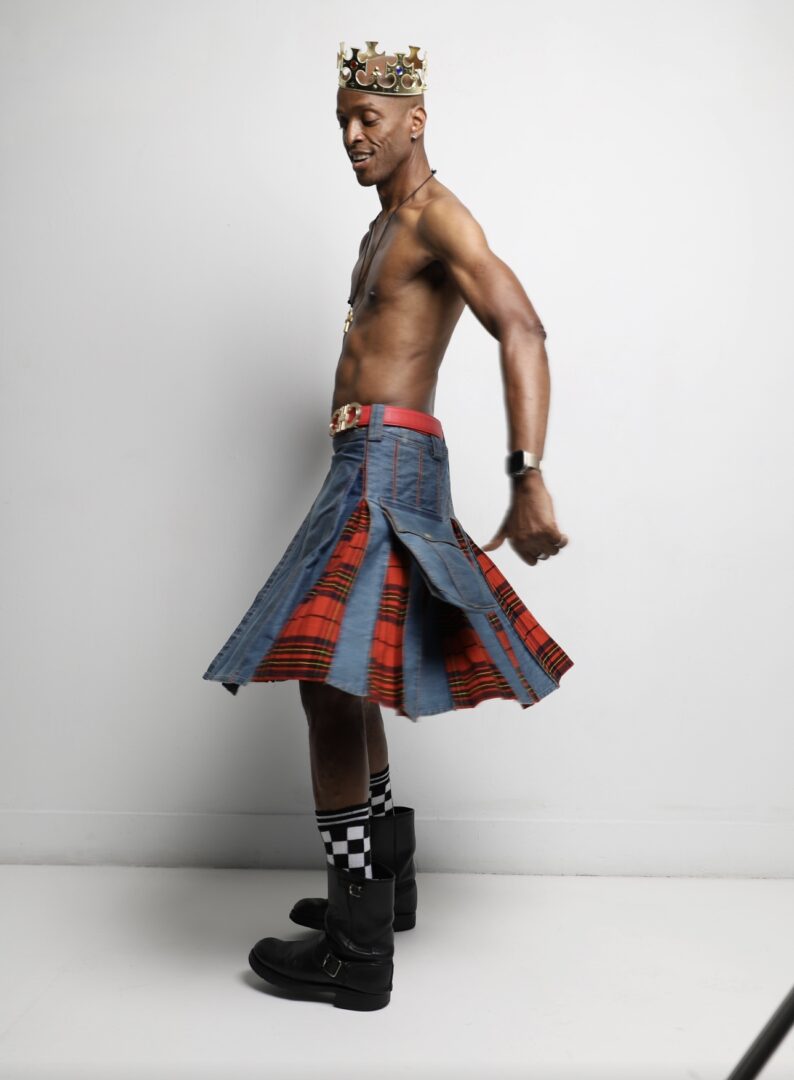

My name is Jason Duval Hunter, and I am a writer, producer, actor, and director. I have a production company called The Hunt4Love Productions, based here in New York City.

I’m currently working on a couple of scripts. One project I’ve been developing for quite some time— I believe it’s finally coming to what I hope will be its final edit so we can begin pitching and selling the film. The working title is Ignore: #ADayInTheLifeOfJay. I’m in the process of producing a showcase to present it to the entertainment industry here in New York City, featuring a cast of talented actors for a staged reading. I’m extremely excited about that.

Ignore: #ADayInTheLifeOfJay is a autobiographical script, using creative license to tell the story of my life—from childhood trauma to adult survivorship, and eventually becoming an advocate for other survivors of childhood trauma.

Another major project I’m working on is a pilot for a TV series that I co-wrote with my writing and producing partner, Karolina Larion. The series is titled Break a Leg. It’s currently being edited and workshopped, and we’re in the process of casting roles and actors for the pilot, with plans to hold a staged reading either by the end of the year or at the start of next year.

Break a Leg, on the other hand, is a behind-the-scenes look at a Broadway show and all the drama that unfolds before the curtain rises. When they say “Break a leg,” in this story, they really mean it!

Those are the two major projects I’m currently working on here in New York. And that’s a little bit about me.

Okay, so here’s a deep one: What was your earliest memory of feeling powerful?

Ironically, my first memory of feeling powerful is something I wrote about in my script about my life, entitled Ignore: A Day in the Life of Jay. I was about eleven years old when it happened.

I wrote a letter to my mother, which I now call “The Letter to Nowhere,” because at the time, I didn’t have an address for her or any idea where to send it. But something in my spirit told me to write it anyway. It was part diary, part desperate message—a way of trying to figure out how to get back to my mother, who had sent me to live with my father and his family in Georgia for the summer. They ended up keeping me far longer than that—I was there for about four years—and I wanted nothing more than to come home to my mom.

So I wrote this letter, pouring out how unhappy I was and how I dreamed of running away and finding my way back to New York City. When I finished writing it, my cousin—who was also the person abusing me at the time—came up onto the porch where I was sitting. He asked to see the letter, and I told him absolutely not. I said it was private, meant only for my mother.

He demanded, “Give me the letter.” And for the first time in my life—at just eleven years old—I fought back. We got into a physical fight over that letter. I remember feeling terrified and angry, but also powerful. For once, I wasn’t going to let him take something that belonged to me—something that represented my voice, my truth.

He was older, bigger, and stronger, so he eventually beat me up and took the letter anyway. He gave it to my aunts and grandparents, and not long after that—maybe the next day or so—my family put me on a bus by myself from Georgia back to New York City.

That’s how I escaped Georgia. And I’ll never forget the feeling that came over me then: that somehow, by simply writing that letter, I had found the power to change my own life—to escape my childhood trauma. It was an unbelievable powerful move on my part in hindsight.

Do you remember a time someone truly listened to you?

A time that I felt most listened to was when I started therapy through a program at Mount Sinai Hospital called the SAVI Program—which stands for Sexual Assault and Violence Intervention.

Over the years, I’ve had several therapists who have been extremely helpful in helping me maintain my mental health. But when I was referred to the SAVI Program, I didn’t know quite what to expect. The program offers counseling specifically geared toward people who have experienced sexual trauma, including childhood sexual abuse.

When I began therapy there, I was paired with a counselor who truly helped me heal. For the first time, I felt like I had a safe space—a place where I could take as much time as I needed to process my childhood trauma and the sexual abuse I had experienced.

I remember my very first session with her. She welcomed me into her office, and the environment felt calm and comfortable. She said, “Okay, let’s start at the beginning.”

I asked, “The beginning? The beginning of what?”

She smiled and said, “The beginning of your life. Let’s start there.”

And I said, “Well, how much time do we have?”

She told me, “Don’t worry about time. We’ll take it one day at a time.”

That moment was powerful for me. I went back to the beginning, and through that process, I learned so much about myself—with her help. I’m forever grateful to my counselor at the SAVI Program.

To this day, we still keep in touch. I now volunteer with the SAVI Program as a guest speaker and advocate, sharing my life story during training sessions for new advocates. I also volunteer in the ER, helping other survivors of domestic abuse and sexual assault.

That’s where I felt most listened to—at the SAVI Program at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Next, maybe we can discuss some of your foundational philosophies and views? What’s a belief or project you’re committed to, no matter how long it takes?

The project that I’m most committed to—no matter how much time it takes—is getting Ignore: A Day in the Life of Jaycompleted and filmed.

Initially, when I wrote the script, I envisioned it as a potential Broadway play or musical. After several edits, it evolved into something I thought could work as a limited series—something for Netflix, HBO, or one of the major streaming platforms.

Now, after this latest round of revisions—which honestly feels like I’ve been working on it for forever plus one day—I see it more as a feature film. It’s very cinematic in scope and emotion.

These things take time, and what I’ve learned throughout this process is that writing Ignore—from that very first letter I wrote when I was eleven years old, to the scripts I’m writing now, forty years later—has always been a cathartic experience for me.

Writing my life story in the form of a film has allowed me to heal, reflect, and rediscover who I am. I love the process. I’m learning so much about myself and about others through the act of creating it.

And no matter how long it takes, I will absolutely get this film done.

Thank you so much for all of your openness so far. Maybe we can close with a future oriented question. Are you doing what you were born to do—or what you were told to do?

I believe I am doing what I was born to do. I was definitely born to be a writer and an actor. From my earliest memories, I’ve always loved television and movies. I was a very creative child, always imagining, observing, and expressing.

As I mentioned earlier, I now realize that my writing journey—or my understanding of myself as a writer—began very young. I was always writing: cards, letters, little stories.

That letter I wrote to my mother—the Letter to Nowhere—was, in hindsight, the beginning of my passion for writing. It was also the start of me using writing as a cathartic experience—a way to heal, express, and make sense of my world.

So yes, I believe I was born to be a writer, an actor, and a creative

But I’ve also discovered what feels like a second calling: advocacy work. I truly love the work I do with the SAVI Program at Mount Sinai Hospital—teaching and helping to train new advocates who go into the ER to support survivors.

I believe I was also born to do this kind of work—to stand with and speak for other survivors of childhood sexual assault and domestic violence.

Those are the things I was born to do.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jduvalhunter?igsh=YWF1aWh0dzFsMnly&utm_source=qr

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/share/17BPbNthRt/?mibextid=wwXIfr

- Youtube: https://youtube.com/@thehunt4lovemovement?si=0JiqgtF81GWAwfal

- Soundcloud: https://on.soundcloud.com/W8l6EcBIFAEaMlH9Hz

Image Credits

Michael Letterlough Jr.

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.