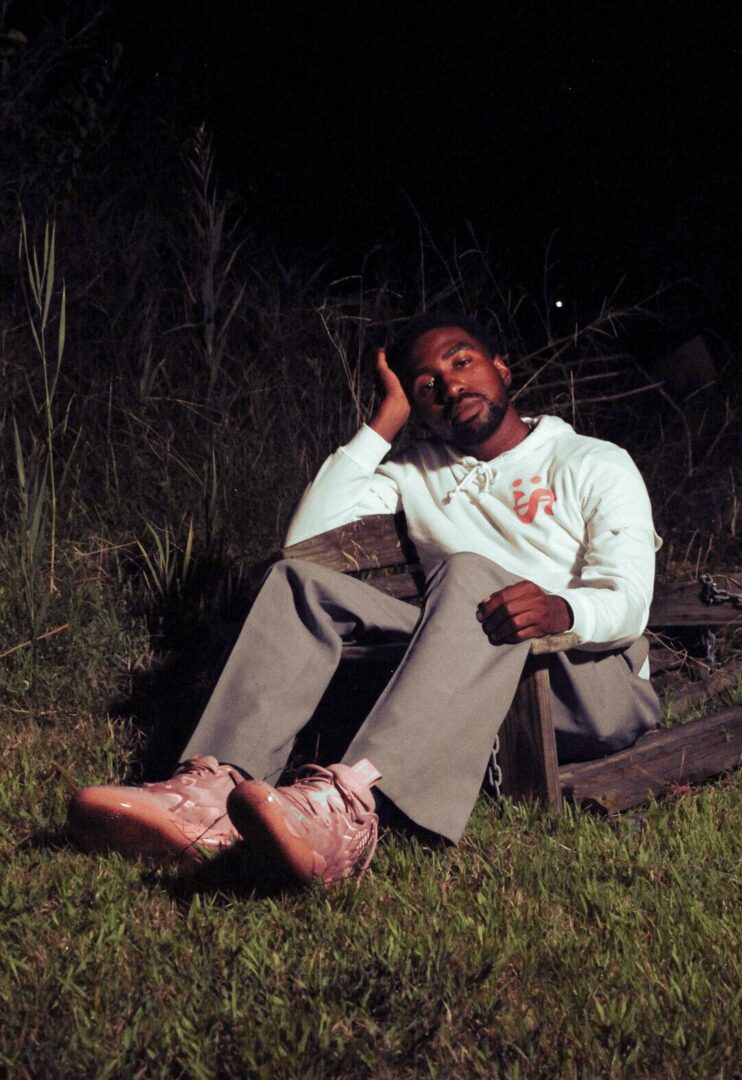

We’re looking forward to introducing you to sangho han. Check out our conversation below.

Good morning sangho, we’re so happy to have you here with us and we’d love to explore your story and how you think about life and legacy and so much more. So let’s start with a question we often ask: Who are you learning from right now?

Right now, I’m learning from circumstances rather than figures.

I’m learning from moments when things don’t resolve cleanly—when effort doesn’t immediately become meaning. I’m learning from the friction between intention and outcome, from repetition, fatigue, and the quiet persistence required to keep working anyway. These conditions have become my teachers.

I’m also learning from my partner—through proximity, disagreement, care, and shared endurance. Living closely with another person over time teaches a different kind of attention: how to listen without trying to fix, how to stay when clarity doesn’t arrive. That has deeply affected how I think about responsibility in making work.

In the studio, I learn from the work itself. From what resists me, from surfaces that refuse to behave, from marks that collapse or contradict each other. I’m less interested in mastery now than in staying present long enough to recognize what the work is asking of me.

If I’m learning from anything, it’s from continuing without certainty—and allowing that condition to shape both how I live and how I paint.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

I’m Sangho Han, a visual artist based in New York. My practice is rooted in painting, but it often extends into drawing, construction, and reconfiguration. I work with canvas, wood, paper, and architectural surfaces, frequently joining multiple supports into a single work and then rearranging or partially undoing them in response to space.

What drives my work is not completion but confrontation—an ongoing negotiation between making and erasing, control and collapse. I’m interested in how images are formed, destabilized, and reassembled, and how persistence itself becomes a material. Rather than aiming for resolution, I treat painting as a site of responsibility: to memory, to labor, and to the conditions under which work is made.

Currently, I’m continuing to develop large-scale, modular paintings that can shift in structure depending on their installation, allowing each exhibition to become a new articulation rather than a fixed endpoint.

Thanks for sharing that. Would love to go back in time and hear about how your past might have impacted who you are today. What was your earliest memory of feeling powerful?

My earliest memory of feeling powerful wasn’t loud or triumphant. It was quiet.

I was a child, drawing alone, realizing that a line I made could stay. That it could hold something—attention, feeling, time—without needing permission. Nothing around me changed, but something inside me did. I understood, even then, that I could make a mark and the world would have to adjust to it, however slightly.

Later, that sense of power shifted. It became less about control and more about endurance—about continuing to work, to observe, to stay with uncertainty when there was no guarantee of recognition or reward. But that first moment remains important to me: the realization that making something, however fragile, was a way of asserting presence.

That’s still where my sense of power lives—not in domination or certainty, but in the ability to remain engaged, to keep making, and to refuse disappearance.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

Yes. More than once.

There were periods when continuing felt irrational—when the effort outweighed any visible outcome, and the language I had relied on to justify making work no longer functioned. During those times, it wasn’t just art that felt impossible, but the idea of moving forward at all. The distance between what I believed in and what I could actually sustain became painfully clear.

What stopped me from fully giving up wasn’t conviction or optimism. It was responsibility—toward my partner, toward the work itself, and toward the time already invested. I didn’t continue because I was certain; I continued because stopping felt like a deeper form of erasure.

I learned that not giving up doesn’t always look heroic. Sometimes it looks like staying quiet, working smaller, lowering expectations, and allowing persistence to replace belief. That shift changed my relationship to both failure and survival—and it’s something that still shapes how I work today.

So a lot of these questions go deep, but if you are open to it, we’ve got a few more questions that we’d love to get your take on. How do you differentiate between fads and real foundational shifts?

I try not to judge too quickly by appearance or popularity. Fads usually announce themselves loudly—they move fast, seek agreement, and depend on constant visibility to survive. They offer a sense of belonging, but that belonging is often conditional and short-lived.

Foundational shifts are quieter. They tend to arrive slowly, sometimes even clumsily, and often feel uncomfortable at first. They don’t resolve things; they complicate them. Instead of providing new answers, they change the kinds of questions that feel necessary. You notice them not because everyone is talking about them, but because your way of working or thinking can no longer return to what it was before.

For me, the real test is time and resistance. If something continues to matter after the initial excitement fades—if it still holds up under boredom, repetition, and doubt—then it’s likely structural rather than fashionable. Foundational shifts don’t ask to be adopted; they insist on being lived through.

Okay, so let’s keep going with one more question that means a lot to us: What do you think people will most misunderstand about your legacy?

I think people might misunderstand my work as being about struggle for its own sake—about difficulty, anger, or endurance as an aesthetic. From the outside, the gestures can look confrontational, unresolved, even hostile.

But what’s often missed is that the work isn’t driven by conflict alone. It comes from care. From a commitment to stay with things that are unfinished, damaged, or contradictory rather than discarding them. The repeated acts of erasing, reworking, and reconfiguring aren’t refusals of meaning—they’re attempts to hold meaning without simplifying it.

If there is a legacy at all, I hope it’s understood not as a record of resistance, but as a record of attention: to time, to responsibility, and to the quiet persistence required to keep making when clarity doesn’t arrive.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.sanghohanart.com

- Instagram: sanghohanart

Image Credits

sangho han

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.