We’re looking forward to introducing you to Shelli aka Rochelle Lipton. Check out our conversation below.

Hi Shelli aka Rochelle, thank you for taking the time to reflect back on your journey with us. I think our readers are in for a real treat. There is so much we can all learn from each other and so thank you again for opening up with us. Let’s get into it: What do the first 90 minutes of your day look like?

Morning Rituals of a Snowbird: A Journey Between Two Worlds

As a Snowbird, my mornings in the South sway to a different rhythm than upstate New York’s chillier dawns. The first 90 minutes of my day here unfold quietly, steeped in respect for the lush, tropical greenery and the comforting embrace of the equatorial warmth.

At daybreak, I rise earlier than the nearby birds, greeted by the soft light spilling through the window. Outside, I notice smoke curling upward—last night’s landscapers left a slow-burning pile of foliage and wood cuttings smoldering unattended on the sand. At 6:30 am, I keep a vigilant eye, a silent guardian of this fragile flame.

Ready to embrace the day, I reach for my handcrafted pottery mug—a treasure lettered “Mazatlan” and adorned with delicate floral artwork. Within it, organic coffee or tea awaits, kept warm overnight by a trusty hotpot. Living with photovoltaic solar panels has made me mindful of conserving electricity; brewing coffee with care, using hotpots and thermoses to cradle warmth or coolness, feels like a necessary act of harmony with nature. It conserves fossil fuels and guards the battery backup.

Emails and messages arrive next, a daily tide mostly swept away without a second glance. Despite my attempts to unsubscribe, relentless marketers refill the inbox without fail. Business emails are answered in a timely fashion. I move on to social media to friends posts mostly in solidarity. Then there are some confrontational posts. I’m accepting their rights to their opinion as to a debate. When truth is uncomfortable, gossip takes its place: facts give way to insults, and when arguments fail, personal attacks emerge.

News than claims much of my morning ritual. I flit between sources— Newser quick updates, International’s breadth, Nation magazine’s thoughtful essays, and even the spectrum from Christian Science Monitor, Washington Post to Fox News. Engaging with a mosaic of viewpoints reminds me that journalism’s lens shapes realities differently—balancing liberal and conservative perspectives grants a fuller picture.

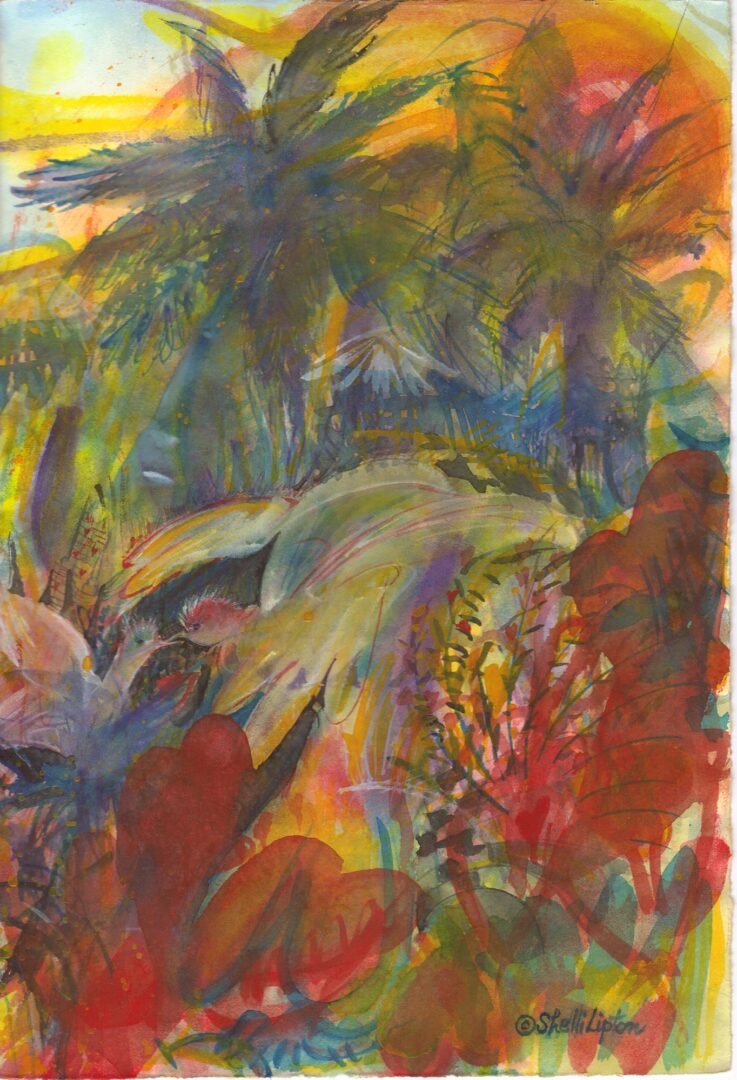

Finally, I settle into sewing, mending and creating with dedication to save fabric from becoming rag and develop my personal embroidery stitching as a unique art form. Read my stitch as you would read painterly brushstrokes. It’s my way of staying grounded and mindful, nurturing craft and conscience with a low Carbon footprint.

This is the gentle dance of a snowbird’s morning—a blend of vigilance, reflection, and simple pleasures—embodied in the warmth of the South, even as my heart carries the chill of my northern home.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

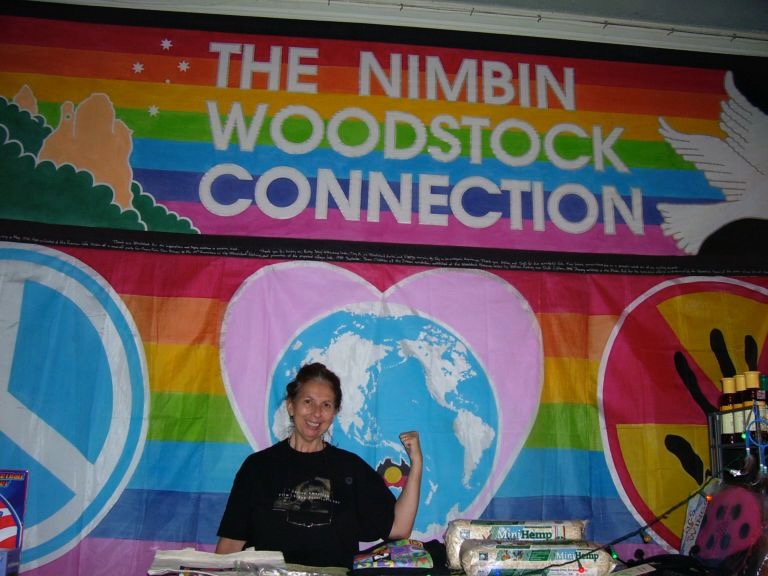

An artist and pioneer, I founded the Woodstock Museum®️ nearly 40 years ago to honor the peace, love, and sustainable ideals of the alternative generation—promoting solar, wind, water energy, mindfulness and consensus-based governance rooted in ‘60s values often overlooked in history.

In my art career, I was the first woman Art Director on Madison Avenue and launched my own recognized agency, transforming the National Audubon Society into a leading environmental organization in 1972. I created the groundbreaking Children’s Art Collection®️ greeting cards, which earned global royalties and led me to speak at major industry events and collaborate with Hallmark and American Greetings.

As the first woman active member of the Art Director’s Club, I’m known for innovative designs like furniture made from wire cable reels, with pieces held in major collections such as Bassett Furniture Company Museum. I also invented strategy games like Quirk, hailed as one of the top ten in its genre,

A solar innovator, I installed the first line tied photovoltaic system that sold excess power back to the grid, refining technologies to ensure worker safety. This work led to teaching installation workshops and instigated Woodstock Museum Board Member Richard Gottlieb to license accredited installers in New York State.

I believe art develops spatial intelligence and performance skills. Art school teaches tools, but true artistry comes from talent, willpower, and pushing beyond limits—qualities I embraced to build my career and identify as an artist.

Appreciate your sharing that. Let’s talk about your life, growing up and some of topics and learnings around that. Who saw you clearly before you could see yourself?

It was my first day of kindergarten, and I already knew it would be special. My mom had bought me a brand-new dress, shiny shoes, even new underwear. Going to school felt like a milestone—a sign that I was growing up. I took this seriously. In my bright red pencil case, I carried two yellow pencils (still unsharpened), a silver pencil sharpener, some pocket change, and a handkerchief. My name was neatly written on the corner of the case, though my mom, wanting it to be perfect, had done the writing for me.

I was four and a half years old that sunny September afternoon, attending the afternoon session of half-day kindergarten. The school, PS105, was just across the street. We entered through the teacher’s entrance where a friendly woman was greeting my mother and the other parents. Some children were crying; I was not.

Inside the classroom, mother waved goodbye and left, while I was welcomed by a kind teacher who told me to “take a seat.” My desk was a charming old wooden one, with a groove to keep pencils from rolling and an opening underneath for supplies. On it lay a small jar of white paste, a yellow pencil, a box of crayons, and a sheet of Manila paper ready for a drawing assignment.

After introductions, we learned how to hang our coats on hooks in a long open closet—each hook marked with a number to remember. Watching my classmates, many of whom I recognized from the neighborhood. I felt comfortable and curious. The teacher explained that we would draw a design. This was perfect for me—I loved to draw.

The teacher’s assistant picked up all the papers, checking that names were written on each. Then our teacher showed us a huge portfolio with partitions, four times the size of our drawings, where the class’s artwork would be stored.

Suddenly, the teacher called out two names:Rochelle Lipton and Jeffrey Koblick. Both of us were chosen to create large designs to decorate this special portfolio. My heart raced—not with excitement this time, but with a sudden unexplained fear. Could I do something as beautiful again? This was my very first panic attack, though I didn’t know how to name it then.

While the other children played, I focused on my big design, wanting it to be perfect.

That moment, that recognition from my teacher was profound. Later on, my drawings were not only stored but starred and hung proudly on the classroom wall long after other children’s art was filed away. It was then that I understood I was the class artist.

On Parent’s Day, my teacher told my parents I was truly gifted in art, urging them to buy me adult art supplies to nurture my talent. From then on, my mom and dad took me to the neighborhood art store to buy paints, brushes, and books. I had my own sketchbook and learned to draw from life.

My kindergarten teacher saw in me what I could not yet see for myself—an artist in the making. Her belief gave me the confidence to believe in myself more deeply and work harder at every artistic endeavor. That early faith shaped my identity, and every teacher who followed only encouraged it further.

I went back to PS105 in the eighth grade with my mother to research if the school kept any of my

art. There on the Principal’s wall was a drawing of a bird in a nest done in pen and ink. Miss Halleran, the Principal said it was from the third grade. When they painted her office they always painted around it. It was too old to remove. I was accepted to Music & Art High School and attended that specialized school from 1960 to 1964.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

It was 1963, the start of my senior year at Music & Art High School, the school the movie “Fame” emulated. Our homeroom teacher assigned us to make a list of potential colleges. The idea of art college excited me—my brother was already at NYU.

When I mentioned it to my mother, her response was blunt and discouraging: “We don’t have the money to send you to college. It’s more important for boys to go. NYU is expensive, and we barely manage for your brother, who’s even taking a loan.”

I was crushed. I shut myself in my room, overwhelmed by disappointment. It felt like old-fashioned thinking especially since girls my age were starting to pursue higher education instead of early marriage, which I hadn’t even considered.

City College was free, but it was known for teacher’s training, not art. My mother pushed me to become a teacher, citing all the holidays and summers off. I refused. “I want to do art,” I said firmly.

Determined, I auditioned for a Saturday art program at Pratt. I got in, commuting hours every Saturday from the Bronx to Brooklyn, believing maybe I could go to Pratt for college.

My aunt, who had attended Sarah Lawrence on scholarship when female college attendance was rare, advocated for me. She challenged my mother’s thinking. Soon after, my mother showed me a New York Post article about a tuition-free talent scholarship test at the School of Visual Arts. I doubted I would get it, but she urged me to try—and I won the scholarship.

I was also accepted to Cooper Union, a prestigious art school, but I never applied to Pratt due to tuition costs.

From nearly giving up, I moved to “I made it.” I learned the power of persistence—where there’s a will there’s a way. Even so, I never fully forgave my mother’s initial negativity, and the topic was never discussed again.

Alright, so if you are open to it, let’s explore some philosophical questions that touch on your values and worldview. What do you believe is true but cannot prove?

One day, my friend Ben Magic stopped by for a chat, and our conversation turned to dowsing. I mentioned that my father was a dowser, which immediately caught Ben’s attention. “You may have that gift,” he said. “Have you ever dowsed”? Answering “no”, Ben asked me for pliers and two metal hangars. Within minutes, he made me my first set of divination rods.

I held each rod, handle by my side straight out, walked the path along the house, and just past a big pine tree my rods crossed. An energy beyond my imagination that took hold. Ben said, “there’s a water vein under there”. Years later when we installed an underground swimming pool, parallel to that spot water shot upwards during the dig. We could have had that spring filling the pool naturally but it was icy cold. We put a drain in and closed it off. That was my first proof that I dowsed successfully reaching that same spring.

My interest grew more seriously. I started reading about dowsing. One book suggested that girls inherit the gift of dowsing from their father and boys inherit the gift from their mother. It seemed to all be making sense now. Dowsing, also known as divining or water witching, is a traditional practice used to locate underground water, minerals, gemstones, buried metals, or even archeological remains and other hidden objects without scientific instruments.

It often involves the use of tools like forked rods, pendulums, or Y-shaped branches, which are believed to respond to subtle energies or “transmissions” from the objects being sought. Keen on trying what I perceived to be a more professional set of rods my other friend brought me back a set from Russia. The metal rods have an additional bone covering on the handles. Equal in its power to the metal hangars I saw no difference; both working.

More recently I dowsed on a lot in Mexico in close view of the salt sea of Cortez. The success was reaching sweet water and high pressure volume. The Mexican diggers proudly sent videos with the water spurting upwards. I had walked that property three times on different days. That spot was the only spot on this 30’ X 60’ foot lot where the rods crossed every time.

I was so sure of reaching drinkable water after three rounds of successful rod crossings despite efforts to convince me just yards away that the earth sunk around the banana tree marked the water, I trusted my rods. After three walks, my confidence only grew.

Albert Einstein, often skeptical of pseudoscience, once said about dowsing: “I know very well that many scientists consider dowsing as they do astrology, as a type of ancient superstition. According to my conviction, this is, however, unjustified. The dowsing rod is a simple instrument which shows the reaction of the human nervous system to certain factors which are unknown to us at this time.” He acknowledged the reality of dowsing effects—an “uncanny reaction” of the nervous system—even though science cannot yet explain the underlying forces.

At Woodstock Museum®️, I lead dowsing workshops where participants make their own rods and walk paths. Those with the gift find their rods twitching, dipping, or crossing involuntarily. This response is called ideomotor movement—unconscious muscle reactions. I also share information about groups and associations where people passionate about dowsing gather, fostering community around this mysterious, enduring craft.

Before we go, we’d love to hear your thoughts on some longer-run, legacy type questions. What do you think people will most misunderstand about your legacy?

When people hear the word “museum” their minds often jump to exhibits and artifacts. When they hear “Woodstock,” they think of a concert marked by sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll. And when they hear “legacy,” they imagine something grand and monumental. But our truth is different. We are a struggling

museum—not a static relic—but a living museum. We embody the 1960s consciousness every day in how we care for our garden, pursue our art and music, and live our passions. These daily acts hold immense value beyond traditional museum roles like grant chasing or simply retelling Woodstock stories.

Our legacy is much more than preserving history. It’s about keeping alive a vision of art, music, and above all, leadership rooted in peace. This goes beyond the symbolic peace sign; it is about cultivating

real-world change through education—teaching leaders globally to build consensus, innovate alternatives to fossil fuels, learn languages to bridge divides, practice meditation to transform anger, and master persuasive dialogue that creates change without violence.

War is hell—and unchangingly tragic. Yet humanity clings to war and control, prioritizing territory over the power of mutual love and understanding. Our Woodstock is more than a festival; it is a beacon where artists and visionaries gather to live simply and freely, resisting the controls of religion, dictators, patriarchies, and any forces that steal autonomy. True freedom comes from responsible stewardship of peace and mind, grounded in compassion.

Education is the key—whether it nurtures passion or drives a career. Everyone deserves the chance to live this precious life without hatred or needless struggle, whether born into hardship or facing man-:made environmental and social poisons. When anger breeds fighting among friends and strangers, it clouds the real enemy—the toxic decision makers often hidden from view, benefitting at the expense of the many.

We must ask: how do we change destructive, psychopathic behavior? While not psychologists, we understand the power of reward and intention. Imagine a Woodstock University where the greatest minds collaborate toward a better future fueled by good intentions.

Work gives purpose—everyone should have the opportunity to contribute meaningfully. A helping hand is not a handout but a path to education, care for all creatures and the environment, and recognition that we are one interconnected circle. There should be no division between the “haves” and “have-nots,” no acceptance of inflicted pain or suffering.

My deepest concern is not about my own legacy—it’s about the very survival of life on this planet. This legacy is a call to action for all living beings to engage in preserving a world where peace, creativity, compassion, and responsibility thrive for generations to come.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.WoodstockMuseum.org

- Linkedin: Shelli Lipton

- Facebook: Woodstock Museum

- Youtube: Woodstock Museum

- Other: White Buffalo Multimedia, Inc.

www.Shellilipton.com

www.WoodstockMuseum.com

Donations could be made via website or:

State of NY Office of the Attorney General NY Registration #44-55-19 Woodstock Museum, Inc.

Image Credits

Photos by Nathan Koenig

so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.